We will have two ten-minute breaks: at 7:30 - 7:40; and, at 9:00 pm - 9:10 pm. I will take roll after the second break before you are dismissed at 10 pm.

Pre-Built Course Content

-

Complete and submit Week 7 Quiz 6: Chapters 11 and 12

Humanism is a philosophical and ethical stance that emphasizes the value and agency of human beings, individually and collectively, and generally prefers critical thinking and evidence (rationalism, empiricism) over acceptance of dogma or superstition. The meaning of the term humanism has fluctuated according to the successive intellectual movements which have identified with it.[1] Generally, however, humanism refers to a perspective that affirms some notion of human freedom and progress. In modern times, humanist movements are typically aligned with secularism, and as of 2015[update] "Humanism" typically refers to a non-theistic life stance centred on human agency and looking to science rather than revelation from a supernatural source to understand the world.[2][3]

Renaissance

Main article: Renaissance humanism

Once the language was mastered grammatically it could be used to attain the second stage, eloquence or rhetoric. This art of persuasion [Cicero had held] was not art for its own sake, but the acquisition of the capacity to persuade others – all men and women – to lead the good life. As Petrarch put it, 'it is better to will the good than to know the truth'. Rhetoric thus led to and embraced philosophy. Leonardo Bruni (c. 1369–1444), the outstanding scholar of the new generation, insisted that it was Petrarch who "opened the way for us to show how to acquire learning", but it was in Bruni's time that the word umanista first came into use, and its subjects of study were listed as five: grammar, rhetoric, poetry, moral philosophy, and history".[26]The basic training of the humanist was to speak well and write (typically, in the form of a letter). One of Petrarch's followers, Coluccio Salutati (1331–1406) was made chancellor of Florence, "whose interests he defended with his literary skill. The Visconti of Milan claimed that Salutati’s pen had done more damage than 'thirty squadrons of Florentine cavalry'".[27]

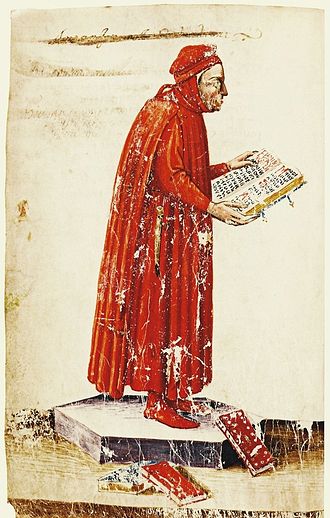

Poggio Bracciolini (1380–1459), an early Renaissance humanist, book collector, and reformer of script, who served as papal secretary[28]

Most specialists now do not characterise Renaissance humanism as a philosophical movement, nor in any way as anti-Christian or even anti-clerical. A modern historian has this to say:

Humanism was not an ideological programme but a body of literary knowledge and linguistic skill based on the "revival of good letters", which was a revival of a late-antique philology and grammar, This is how the word "humanist" was understood by contemporaries, and if scholars would agree to accept the word in this sense rather than in the sense in which it was used in the nineteenth century we might be spared a good deal of useless argument. That humanism had profound social and even political consequences of the life of Italian courts is not to be doubted. But the idea that as a movement it was in some way inimical to the Church, or to the conservative social order in general is one that has been put forward for a century and more without any substantial proof being offered.The umanisti criticised what they considered the barbarous Latin of the universities, but the revival of the humanities largely did not conflict with the teaching of traditional university subjects, which went on as before.[31]

The nineteenth-century historian Jacob Burckhardt, in his classic work, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, noted as a "curious fact" that some men of the new culture were "men of the strictest piety, or even ascetics". If he had meditated more deeply on the meaning of the careers of such humanists as Abrogio Traversari (1386–1439), the General of the Camaldolese Order, perhaps he would not have gone on to describe humanism in unqualified terms as "pagan", and thus helped precipitate a century of infertile debate about the possible existence of something called "Christian humanism" which ought to be opposed to "pagan humanism".

— Peter Partner, Renaissance Rome, Portrait of a Society 1500–1559 (University of California Press 1979) pp. 14–15.

Nor did the humanists view themselves as in conflict with Christianity. Some, like Salutati, were the Chancellors of Italian cities, but the majority (including Petrarch) were ordained as priests, and many worked as senior officials of the Papal court. Humanist Renaissance popes Nicholas V, Pius II, Sixtus IV, and Leo X wrote books and amassed huge libraries.[32]

In the high Renaissance, in fact, there was a hope that more direct knowledge of the wisdom of antiquity, including the writings of the Church fathers, the earliest known Greek texts of the Christian Gospels, and in some cases even the Jewish Kabbalah, would initiate a harmonious new era of universal agreement.[33] With this end in view, Renaissance Church authorities afforded humanists what in retrospect appears a remarkable degree of freedom of thought.[34][35] One humanist, the Greek Orthodox Platonist Gemistus Pletho (1355–1452), based in Mystras, Greece (but in contact with humanists in Florence, Venice, and Rome) taught a Christianised version of pagan polytheism.[36]

Back to the sources

After 1517, when the new invention of printing made these texts widely available, the Dutch humanist Erasmus, who had studied Greek at the Venetian printing house of Aldus Manutius, began a philological analysis of the Gospels in the spirit of Valla, comparing the Greek originals with their Latin translations with a view to correcting errors and discrepancies in the latter. Erasmus, along with the French humanist Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples, began issuing new translations, laying the groundwork for the Protestant Reformation. Henceforth Renaissance humanism, particularly in the German North, became concerned with religion, while Italian and French humanism concentrated increasingly on scholarship and philology addressed to a narrow audience of specialists, studiously avoiding topics that might offend despotic rulers or which might be seen as corrosive of faith. After the Reformation, critical examination of the Bible did not resume until the advent of the so-called Higher criticism of the 19th-century German Tübingen school.

Fig. 13.1 Palazzo Vecchio, Florence. 1299–1310.

At the bottom right, before the main entrance, stands a replica of Michelangelo’s famous sculpture of David (see Fig. 14.30 in Chapter 14). The original was put in place here in 1504. It was removed to protect it from damage in 1873. The replica seen here dates from 1910.THINKING AHEAD

13.1 Compare and contrast civic life in Siena and Florence.

13.2 Outline how an increasingly naturalistic art replaced the Byzantine style in Italy.

13.3 Describe the distinguishing characteristics of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

13.4 Examine how the vernacular style developed after the Black Death.

Papal States

Siena and Florence: Civic and Religious Life in Tuscany 436

Siena: A Free Commune 437

Over the centuries, Siena has had a rich tradition of arts and artists. The list of artists from the Sienese School include Duccio and his student Simone Martini, Pietro Lorenzetti and Martino di Bartolomeo. A number of well known works of Renaissance and High Renaissance art still remain in galleries or churches in Siena.

Madonna and Child with saints polyptych by Duccio (1311–1318).

Madonna and Child with saints polyptych by Duccio (1311–1318).The Church of San Domenico contains art by Guido da Siena, dating to mid-13th century. Duccio's Maestà which was commissioned by the City of Siena in 1308 was instrumental in leading Italian painting away from the hieratic representations of Byzantine art and directing it towards more direct presentations of reality. And his Madonna and Child with Saints polyptych, painted between 1311 and 1318 remains at the city's Pinacoteca Nazionale.

The Pinacoteca also includes several works by Domenico Beccafumi, as well as art by Lorenzo Lotto, Domenico di Bartolo and Fra Bartolomeo.

Sassetta, Institution of the Eucharist (1430–1432), Pinacoteca di Siena.

Sassetta, Institution of the Eucharist (1430–1432), Pinacoteca di Siena.Florence: Archrival of Siena 439

Of a population estimated at 94,000 before the Black Death of 1348,[15] about 25,000 are said to have been supported by the city's wool industry: in 1345 Florence was the scene of an attempted strike by wool combers (ciompi), who in 1378 rose up in a brief revolt against oligarchic rule in the Revolt of the Ciompi. After their suppression, Florence came under the sway (1382–1434) of the Albizzi family, bitter rivals of the Medici.

In the 15th century, Florence was among the largest cities in Europe, considered rich and economically successful. Life was not idyllic for all residents though, among whom there were great disparities in wealth.[16] Cosimo de' Medici was the first Medici family member to essentially control the city from behind the scenes. Although the city was technically a democracy of sorts, his power came from a vast patronage network along with his alliance to the new immigrants, the gente nuova (new people). The fact that the Medici were bankers to the pope also contributed to their ascendancy. Cosimo was succeeded by his son Piero, who was, soon after, succeeded by Cosimo's grandson, Lorenzo in 1469. Lorenzo was a great patron of the arts, commissioning works by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Botticelli. Lorenzo was an accomplished musician and brought composers and singers to Florence, including Alexander Agricola, Johannes Ghiselin, and Heinrich Isaac. By contemporary Florentines (and since), he was known as "Lorenzo the Magnificent" (Lorenzo il Magnifico). Following the death of Lorenzo de' Medici in 1492, he was succeeded by his son Piero II. When the French king Charles VIII invaded northern Italy, Piero II chose to resist his army. But when he realized the size of the French army at the gates of Pisa, he had to accept the humiliating conditions of the French king. These made the Florentines rebel and they expelled Piero II. With his exile in 1494, the first period of Medici rule ended with the restoration of a republican government.

Videos Siena’s Art, 3:24 https://youtu.be/cdO_quYFFv4 Otis Art History 16 - Italian Renaissance - Florence, 5:08 https://youtu.be/s29QCZCCJ-g What's the Difference Between Realism & Naturalism? | ARTiculations, 4:32 Realism in the arts is the attempt to represent subject matter truthfully, without artificiality and avoiding artistic conventions, implausible, exotic and supernatural elements.

Realism has been prevalent in the arts at many periods, and is in large part a matter of technique and training, and the avoidance of stylization. In the visual arts, illusionistic realism is the accurate depiction of lifeforms, perspective, and the details of light and colour. Realist works of art may emphasize the mundane, ugly or sordid, such as works of social realism, regionalism, or kitchen sink realism.

There have been various realism movements in the arts, such as the opera style of verismo, literary realism, theatrical realism and Italian neorealist cinema. The realism art movement in painting began in France in the 1850s, after the 1848 Revolution.[1] The realist painters rejected Romanticism, which had come to dominate French literature and art, with roots in the late 18th century.

Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet, 1854. A Realist painting by Gustave Courbet

Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet, 1854. A Realist painting by Gustave Courbethttps://youtu.be/ofxkDCSxDMU Cimabue's Santa Trinita Madonna & Giotto's Ognissanti Madonna, 6:58 https://youtu.be/DKnFvXmUlOI 1.0 - 6 Rise of Nationalist Literature in the Late Middle Age, 3:56 https://youtu.be/_mpwHXLwauQ The Divine Comedy (Italian: Divina Commedia [diˈviːna komˈmɛːdja]) is an epic poem by Dante Alighieri, begun c. 1308 and completed 1320, a year before his death in 1321. It is widely considered the preeminent work of Italian literature[1] and is seen as one of the greatest works of world literature.[2] The poem's imaginative vision of the afterlife is representative of the medieval world-view as it had developed in the Western Church by the 14th century. It helped establish the Tuscan language, in which it is written, as the standardized Italian language.[3] It is divided into three parts: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso.

Dante shown holding a copy of the Divine Comedy, next to the entrance to Hell, the seven terraces of Mount Purgatory and the city of Florence, with the spheres of Heaven above, in Michelino's fresco

Dante shown holding a copy of the Divine Comedy, next to the entrance to Hell, the seven terraces of Mount Purgatory and the city of Florence, with the spheres of Heaven above, in Michelino's frescoOn the surface, the poem describes Dante's travels through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise or Heaven;[4] but at a deeper level, it represents, allegorically, the soul's journey towards God.[5] At this deeper level, Dante draws on medieval Christian theology and philosophy, especially Thomistic philosophy and the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas.[6] Consequently, the Divine Comedy has been called "the Summa in verse".[7]

The work was originally simply titled Comedìa and the word Divina was added by Giovanni Boccaccio. The first printed edition to add the word divina to the title was that of the Venetian humanist Lodovico Dolce,[8] published in 1555 by Gabriele Giolito de' Ferrari.

Dante's Inferno - Divine Comedy - Realms of the Dead - 7 Deadly Sins - after effects, 4:27 https://youtu.be/4CPug2geRSs The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 75 to 200 million people and peaking in Europe in the years 1346–53.[1][2][3] Although there were several competing theories as to the etiology of the Black Death, analysis of DNA from victims in northern and southern Europe published in 2010 and 2011 indicates that the pathogen responsible was the Yersinia pestis bacterium, probably causing several forms of plague.[4][5]

The Black Death is thought to have originated in the arid plains of Central Asia, where it then travelled along the Silk Road, reaching Crimea by 1343.[6] From there, it was most likely carried by Oriental rat fleas living on the black rats that were regular passengers on merchant ships. Spreading throughout the Mediterranean and Europe, the Black Death is estimated to have killed 30–60% of Europe's total population.[7] In total, the plague reduced the world population from an estimated 450 million down to 350–375 million in the 14th century. The world population as a whole did not recover to pre-plague levels until the 17th century.[8] The plague recurred occasionally in Europe until the 19th century.

The plague created a series of religious, social, and economic upheavals, which had profound effects on the course of European history.

What Was the Black Death? What Were the Symptoms? 4:56

https://youtu.be/y7OWLohZ_fs The Decameron - Book Review | Anymai, 2:18

A sonnet is a poetic form which originated in Italy; Giacomo Da Lentini is credited with its invention.

The term sonnet is derived from the Italian word sonetto (from Old Provençal sonet a little poem, from son song, from Latin sonus a sound). By the thirteenth century it signified a poem of fourteen lines that follows a strict rhyme scheme and specific structure. Conventions associated with the sonnet have evolved over its history. Writers of sonnets are sometimes called "sonneteers", although the term can be used derisively.

https://youtu.be/RhNolM-KySg Shakespearean vs. Petrarchan Sonnet, 3:20

https://youtu.be/jcnfK4WBaok

The Canterbury Tales (Middle English: Tales of Caunterbury[2]) is a collection of 24 stories that runs to over 17,000 lines written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer. In 1386 Chaucer became Controller of Customs and Justice of Peace and then three years later in 1389 Clerk of the King's work. It was during these years that Chaucer began working on his most famous text, The Canterbury Tales. The tales (mostly written in verse, although some are in prose) are presented as part of a story-telling contest by a group of pilgrims as they travel together on a journey from London to Canterbury in order to visit the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. The prize for this contest is a free meal at the Tabard Inn at Southwark on their return.

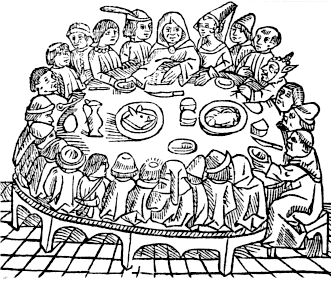

A woodcut from William Caxton's second edition of The Canterbury Tales printed in 1483

A woodcut from William Caxton's second edition of The Canterbury Tales printed in 1483 After a long list of works written earlier in his career, including Troilus and Criseyde, House of Fame, and Parliament of Fowls, The Canterbury Tales is near-unanimously seen as Chaucer's magnum opus. He uses the tales and the descriptions of its characters to paint an ironic and critical portrait of English society at the time, and particularly of the Church. Chaucer's use of such a wide range of classes and types of people was without precedent in English. Although the characters are fictional, they still offer a variety of insights into the customs and practices of the time. Often, such insight leads to a variety of discussions and disagreements to people in the 14th century. For example, although a variety of social classes are represented in these stories and all pilgrims on a spiritual quest, it is apparent that they are more concerned with worldly things than spiritual. Structurally, the collection resembles The Decameron, which Chaucer may have read during his first diplomatic mission to Italy in 1372.

It is sometimes argued that the greatest contribution The Canterbury Tales made to English literature was in popularizing the literary use of the vernacular, English, rather than French, Italian or Latin. English had, however, been used as a literary language centuries before Chaucer's time, and several of Chaucer's contemporaries—John Gower, William Langland, the Pearl Poet, and Julian of Norwich—also wrote major literary works in English. It is unclear to what extent Chaucer was responsible for starting a trend as opposed to simply being part of it.

While Chaucer clearly states the addressees of many of his poems, the intended audience of The Canterbury Tales is more difficult to determine. Chaucer was a courtier, leading some to believe that he was mainly a court poet who wrote exclusively for nobility.

The Canterbury Tales were far from complete at the end of Chaucer's life. In the General Prologue,[3] some thirty pilgrims are introduced. Chaucer's intention was to write two stories from the perspective of each pilgrim on the way to and from their ultimate destination, St. Thomas Becket's shrine. Although perhaps incomplete, The Canterbury Tales is revered as one of the most important works in English literature. Not only do readers from all time frames find it entertaining, but also it is a work that is open to a range of interpretations.[4]

Introduction to Chaucer: Middle English and the Canterbury Tales, 7:29 https://youtu.be/TSLaGOSuCUw

Women in the Middle Ages, 4:19

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iJmI8PlBc34

Painting: A Growing Naturalism 440

Duccio and Simone Martini 440

Cimabue and Giotto 442

Dante and the Rise of Vernacular Literature in Europe 446

Dante’s Divine Comedy 446

The Black Death and Its Literary Aftermath 449

Literature after the Black Death: Boccaccio’s Decameron 451

Petrarch’s Sonnets 453

Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales 454

Women in Late Medieval Society 455

READINGS

13.1 from Dante, Inferno, Canto 1 460

13.2 from Dante, Inferno, Canto 34 448

13.3 from Dante, Paradiso, Canto 33 449

13.4 from Boccaccio, Decameron 451

13.5 from Boccaccio, Decameron, Dioneo’s Tale 462

13.6 Petrarch, Sonnet 134 454

13.7 from Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales, Prologue 454

13.8 from Boccaccio, Decameron, Filippa’s Tale 463

13.9 from Christine de Pizan, Book of the City of Ladies 456

13.10 Christine de Pizan, Tale of Joan of Arc 457

FEATURES

CLOSER LOOK Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel 444

MATERIALS & TECHNIQUES

Tempera Painting 446

Buon Fresco 447

CONTINUITY & CHANGE The Dance of Death 458

PART THREE THE RENAISSANCE AND THE AGE OF ENCOUNTER 1400–1600 464

Chapter 14 Florence and the Early Renaissance HUMANISM IN ITALY 467

The State as a Work of Art: The Baptistery Doors, Florence Cathedral, and a New Perspective 468

The Gates of Paradise 470

Florence Cathedral 472

Scientific Perspective and Naturalistic Representation 472

Perspective and Naturalism in Painting: Masaccio 476

The Classical Tradition in Freestanding Sculpture: Donatello 478

The Medici Family and Humanism 479

Cosimo de’ Medici 479

Lorenzo the Magnificent: “… I find a relaxation in learning.” 482

Beyond Florence: The Ducal Courts and the Arts 486

The Montefeltro Court in Urbino 486

The Gonzaga Court in Mantua 488

The Sforza Court in Milan and Leonardo da Vinci 489

Florence after the Medici: The New Republic 493

READINGS

14.1 from Poliziano, Stanzas for the Joust of Giuliano de’ Medici (1475–78) 483

14.2 “Song of Bacchus,” or “Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne,” from Lorenzo de’ Medici: Selected Poems and Prose 485

14.3 from Pico della Mirandola, Oration on the Dignity of Man (1486) 485

14.4 from Baldassare Castiglione, The Book of

the Courtier, Book 1 (1513–18; published 1528) 497

14.5 from Giorgio Vasari, “Life of Leonardo: Painter and Sculptor of Florence,” in Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Architects, and Sculptors (1550, 1568) 498

FEATURES

CLOSER LOOK Brunelleschi’s Dome 474

CONTINUITY & CHANGE Michelangelo in Rome 495

LECTURE

Chapter 13 Siena and Florence in the Fourteenth Century TOWARD A NEW HUMANISM 435

Siena and Florence: Civic and Religious Life in Tuscany 436

Siena: A Free Commune 437

Florence: Archrival of Siena 439

Painting: A Growing Naturalism 440

Duccio and Simone Martini 440

Cimabue and Giotto 442

Dante and the Rise of Vernacular Literature in Europe 446

Dante’s Divine Comedy 446

The Black Death and Its Literary Aftermath 449

Literature after the Black Death: Boccaccio’s Decameron 451

Petrarch’s Sonnets 453

Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales 454

Women in Late Medieval Society 455

READINGS

13.1 from Dante, Inferno, Canto 1 460

13.2 from Dante, Inferno, Canto 34 448

13.3 from Dante, Paradiso, Canto 33 449

13.4 from Boccaccio, Decameron 451

13.5 from Boccaccio, Decameron, Dioneo’s Tale 462

13.6 Petrarch, Sonnet 134 454

13.7 from Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales, Prologue 454

13.8 from Boccaccio, Decameron, Filippa’s Tale 463

13.9 from Christine de Pizan, Book of the City of Ladies 456

13.10 Christine de Pizan, Tale of Joan of Arc 457

FEATURES

CLOSER LOOK Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel 444

MATERIALS & TECHNIQUES

Tempera Painting 446

Buon Fresco 447

CONTINUITY & CHANGE The Dance of Death 458

PART THREE THE RENAISSANCE AND THE AGE OF ENCOUNTER 1400–1600 464

Chapter 14 Florence and the Early Renaissance HUMANISM IN ITALY 467

The State as a Work of Art: The Baptistery Doors, Florence Cathedral, and a New Perspective 468

The Gates of Paradise 470

Florence Cathedral 472

Scientific Perspective and Naturalistic Representation 472

Perspective and Naturalism in Painting: Masaccio 476

The Classical Tradition in Freestanding Sculpture: Donatello 478

The Medici Family and Humanism 479

Cosimo de’ Medici 479

Lorenzo the Magnificent: “… I find a relaxation in learning.” 482

Beyond Florence: The Ducal Courts and the Arts 486

The Montefeltro Court in Urbino 486

The Gonzaga Court in Mantua 488

The Sforza Court in Milan and Leonardo da Vinci 489

Florence after the Medici: The New Republic 493

READINGS

14.1 from Poliziano, Stanzas for the Joust of Giuliano de’ Medici (1475–78) 483

14.2 “Song of Bacchus,” or “Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne,” from Lorenzo de’ Medici: Selected Poems and Prose 485

14.3 from Pico della Mirandola, Oration on the Dignity of Man (1486) 485

14.4 from Baldassare Castiglione, The Book of

the Courtier, Book 1 (1513–18; published 1528) 497

14.5 from Giorgio Vasari, “Life of Leonardo: Painter and Sculptor of Florence,” in Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Architects, and Sculptors (1550, 1568) 498

FEATURES

CLOSER LOOK Brunelleschi’s Dome 474

CONTINUITY & CHANGE Michelangelo in Rome 495

- Chapter 13: Siena and Florence in the Fourteenth Century

- Chapter 14: Florence and the Early Renaissance – in Italy

- Complete and submit Week 7 Quiz 6: Chapters 11 and 12

- Read the following from your textbook:

- Chapter 13: Siena and Florence in the Fourteenth Century

- Chapter 14: Florence and the Early Renaissance – in Italy

- View the Week 7 Would You Like to Know More? videos

- Explore the Week 7 Music Folder

- Do the Week 7 Explore Activities

- Participate in the Week 7 Discussion (choose only one (1) of the discussion options)

Resources on the Renaissance

Medici

Humanism

Horrible Histories: Renaissance Dragon's den:Leonardo da Vinci Ingenious Inventions. Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, slowly paints the Sistine Chapel ,unseen clip.

Leonardo Da Vinci biography | Life of Leonardo Da Vinci documentary [Biography of famous people]

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci 15 April 1452 – 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath, painter,.

Leonardo da Vinci was one of the most prolific inventors of all time! Some of Leonardo da Vinci's inventions that are most well known are Leonardo da Vinci's flying machine invention, Leonardo.

Renaissance according to Horrible Histories

http://youtu.be/bP0WWUyUCAQ 4:39History (based on materials from the Grove Dictionary of Music): Though perhaps most familiar to the general public as one of the earliest successful operatic composers, Claudio Monteverdi's (1567-1643) most lasting project was actually the composition of madrigals which was begun in the composer's early twenties, resulting in the publication of eight complex tomes during Monteverdi's lifetime and an additional collection a few years after his death. The eighth book, titled "Madrigali dei guerrieri ed amorosi", is generally regarded as the composer's masterwork, and, indeed, it is a monumental 1638 tome containing nearly 40 individual works which offers an overview Monteverdi's work of the previous two decades; the pieces are carefully arranged into particular sequences, suggesting that the book be examined as a whole work rather than an arbitrarily ordered collection. Many of the pieces in the collection are in "genere rappresentativo" as opposed to the madrigals "senza gesto" ("without gesture"), indicating that the performance of the book would have been at times highly theatrical. Each subdivision of the book is marked by a madrigal for larger-than-normal vocal and instrumental forces. It is in this collection or, to be precise, among its "Amorous madrigals" part where we encounter perhaps one of Monteverdi's most engaging works: the Lament of the Nymph.

The Medici: Godfathers of Humanism, 55:22

Lorenzo de' Medici becomes a driving force of the Renaissance; monk Savonarola promotes fundamentalist purification of Florence after the death of Lorenzo de' Medici.

http://youtu.be/iBlGkTTol9E

Great Minds: Leonardo da Vinci, 9:20

Leonardo da Vinci was one of the most diversely talented individuals of all time. His "unquenchable curiosity" led him to make discoveries and inventions that were beyond his time, not to mention his numerous artistic masterpieces. Today on SciShow, Hank takes us into the mind of this Renaissance Man and explores some of his many contributions to the world.

http://youtu.be/kMf8hFBJylA

The controversial art of Michelangelo, 5:14

Michelangelo destroyed many of his drawings and sketches later in life, thinking that only the perfect ones should survive him. This is partly the reason why the attribution of his work is quite controversial. Art historians believe there are about 600 drawings by Michelangelo. Swiss expert Alexander Perrig says only about 100 are authentic. (SF Kulturplatz/swissinfo.ch)

http://youtu.be/j92Tsi0bVDY

Florentine Renaissance, 3:39

Production: SCAD Media, LLC http://www.scad-media.com

HSP Summer 2013

The Renaissance begins in Italy and is an invention of the Florentines. This seminar is an examination of the art, architecture, sculpture, literature, and history of the republic of Florence during its period of greatest importance to world history. From the mid-14th to the late 15th century, Florence was the center of a cultural movement that has become the definition of the modern world.

We will begin by examining the first glimmerings in the frescoes of Giotto, the literary works of Petrarch and Boccaccio, the sculptural work of Donatello and Ghiberti, and the architecture and engineering of Brunelleschi. We will study the dynamics of the network of thinkers at the court of Lorenzo de'Medici, including Poliziano, Marsilio Ficino, Pico della Mirandola, and Botticelli.

As artistic experimentation with anatomy, musculature, and linear perspective accelerate throughout the 15th century, we will follow the work of the great artists Fra Angelico, Verrochio, Pollaiuolo, and others, and we will study Benozzo Gozzoli's frescoes in the Medici-Ricardi Palace.

We will also follow the fortunes of the republic of Florence in its ups and downs, including the 1478 Pazzi Conspiracy and the career of Savonarola. Through these political upheavals the cultural expressions of Florence still triumph in the High Renaissance masterpieces of Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo. We will read Machiavelli's Prince, and examine Mannerism in the work of Rosso Fiorentino, Parmigianino, Pontormo, and Bronzino.

Reading brief selections from the period, we will have occasion to consider Lorenzo de' Medici's songs, the role of St. Francis of Assisi, the sonnets of Michelangelo, Petrarch's letter to Dionisio da Borgo San Sepolcro, Machiavelli's letter to Francesco Vettori, and the mathematical and philosophical musings of Leonardo da Vinci. Using all these works, we will try to come to a deeper understanding of the key role played by Florence and its unique culture in initiating a new period of human history, one characterized by observation, rigorous craftsmanship, experimentation, resistance to authority (but respect for the ancients), and an abiding belief that man is the measure of all things.

There may be one book on Florentine Renaissance art (to be named later),and some brief selections from these texts:

Vasari, Lives of the Artists. Boccaccio, Decameron. Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier Machiavelli, The Prince Galileo, Sidereus Nuncius.

Richard Poss is an Associate Professor in Astronomy and former Director of the Humanities Program at the University of Arizona. His research examines the role of astronomical themes in European poetry, and he has published articles on Petrarch, Dante, Veronica Gambara, Walt Whitman, and on the exploration of Mars. He teaches courses on the history of astronomy and the relations between astronomy and the arts, and is a frequent instructor in the Humanities Seminars program. He is co-founder of the popular lecture series "Astrobiology and the Sacred: Implications of Life Beyond Earth," sponsored by a grant from the Templeton Foundation. He has won a variety of major university teaching awards, including the UA Foundation Leicester and Kathryn Sherrill Creative Teaching Award, the Provost's General Education Teaching Award, and several Humanities Seminars Superior Teaching Awards.

http://youtu.be/4MEykggHNc0

Venetian Art and Culture

Art, culture and Venetian style - Hotel Monaco Grand Canal - Venice, 2:08

http://youtu.be/DXOTbkPfRwY

REFERENCES Beyond the Sound Bites Should the Americans build a wall like the Romans, the Chinese, and at the Vatican?

Vatican Most Restrictive

Vatican Pope vs. Trump Fight Donald Trump Fires Back at Pope Francis, 2:24

Milo Yiannopoulos i-deserve-an-apology-college-students-gather-to-share-wounded-emotions-after-conservative-writers-lecture/

Closing Statement at the University of Bristol