The presentation may contain content that is deemed objectionable to a particular viewer because of the view expressed or the conduct depicted. The views expressed are provided for learning purposes only, and do not necessarily express the views, or opinions, of Strayer University, your professor, or those participating in videos or other media.

We will have two breaks: at 7:30 and 9:00 pm. We will do our in-class discussion before you are dismissed at 10:15 pm.

- Complete and submit Week 7 Quiz 6 covering Chapters 31 and 32 - 40 Points

- Read the following from your textbook:

- Chapter 33: The Fin de Siècle: Toward the Modern – Europe and Africa

- Chapter 34: The Era of Invention: Paris and the Modern World

- Explore the Week 7 Music Folder

- View the Week 7 Lecture videos

- Do the Week 7 Explore Activities

- Participate in the Week 7 Discussion (choose only one (1) of the discussion options) - 20 Points

What is the literal definition of fin de siècle?

|

|||||

Question 2: Multiple Choice

-

Why was Gustave Eiffel's tower so unique for the time?

Why was Gustave Eiffel's tower so unique for the time?Given Answer:  It was twice the height of any other building in the world

It was twice the height of any other building in the worldCorrect Answer:  It was twice the height of any other building in the world

It was twice the height of any other building in the world

Question 3: Multiple Choice

-

On what work did Stépane Mallarmé base his Symbolist "L'Aprés-midi d'un faune"?

On what work did Stépane Mallarmé base his Symbolist "L'Aprés-midi d'un faune"?Given Answer:  Ovid's Metamorphoses

Ovid's MetamorphosesCorrect Answer:  Ovid's Metamorphoses

Ovid's Metamorphoses

Question 4: Multiple Choice

-

Why at the beginning of the twentieth century were Western powers vying to dominate Africa?

Why at the beginning of the twentieth century were Western powers vying to dominate Africa?Given Answer:  To control the natural resources and trade routes

To control the natural resources and trade routesCorrect Answer:  To control the natural resources and trade routes

To control the natural resources and trade routes

Question 5: Multiple Choice

-

Why did the Society of Men of Letters refuse to accept Rodin's Monument to Balzac, forcing him to return the advance payments?

Why did the Society of Men of Letters refuse to accept Rodin's Monument to Balzac, forcing him to return the advance payments?Given Answer:  Not a realistic portrayal

Not a realistic portrayalCorrect Answer:  Not a realistic portrayal

Not a realistic portrayal

Question 6: Multiple Choice

-

Why were Thomas Edison's early films for the Kinetoscope rather limited?

Why were Thomas Edison's early films for the Kinetoscope rather limited?Given Answer:  Only one person at a time could view them

Only one person at a time could view themCorrect Answer:  Only one person at a time could view them

Only one person at a time could view them

Question 7: Multiple Choice

-

Why did early silent films appeal especially to the working-class, immigrant audiences?

Why did early silent films appeal especially to the working-class, immigrant audiences?Given Answer:  They didn't have to understand English

They didn't have to understand EnglishCorrect Answer:  They didn't have to understand English

They didn't have to understand English

Question 8: Multiple Choice

-

Why did The Birth of a Nation establish director D. W. Griffith as a film master?

Why did The Birth of a Nation establish director D. W. Griffith as a film master?Given Answer:  His use of cinematic space

His use of cinematic spaceCorrect Answer:  His use of cinematic space

His use of cinematic space

Question 9: Multiple Choice

-

What special significance does the spiral have in Cubist paintings such as Picasso's Violin?

What special significance does the spiral have in Cubist paintings such as Picasso's Violin?Given Answer:  The interplay between two and three dimensions

The interplay between two and three dimensionsCorrect Answer:  The interplay between two and three dimensions

The interplay between two and three dimensions

Question 10: Multiple Choice

Why was the Der Blaue Reiter artist Wassily Kandinsky obsessed with color?

|

|||||

| |||||

Question 1: Multiple Choice

-

What is the literal definition of fin de siècle?

What is the literal definition of fin de siècle?Given Answer:  End of the century

End of the centuryCorrect Answer:  End of the century

End of the century

Question 2: Multiple Choice

-

Why was Gustave Eiffel's tower so unique for the time?

Why was Gustave Eiffel's tower so unique for the time?Given Answer:  It was twice the height of any other building in the world

It was twice the height of any other building in the worldCorrect Answer:  It was twice the height of any other building in the world

It was twice the height of any other building in the world

Question 3: Multiple Choice

-

On what work did Stépane Mallarmé base his Symbolist "L'Aprés-midi d'un faune"?

On what work did Stépane Mallarmé base his Symbolist "L'Aprés-midi d'un faune"?Given Answer:  Ovid's Metamorphoses

Ovid's MetamorphosesCorrect Answer:  Ovid's Metamorphoses

Ovid's Metamorphoses

Question 4: Multiple Choice

-

Why at the beginning of the twentieth century were Western powers vying to dominate Africa?

Why at the beginning of the twentieth century were Western powers vying to dominate Africa?Given Answer:  To control the natural resources and trade routes

To control the natural resources and trade routesCorrect Answer:  To control the natural resources and trade routes

To control the natural resources and trade routes

Question 5: Multiple Choice

-

Why did the Society of Men of Letters refuse to accept Rodin's Monument to Balzac, forcing him to return the advance payments?

Why did the Society of Men of Letters refuse to accept Rodin's Monument to Balzac, forcing him to return the advance payments?Given Answer:  Not a realistic portrayal

Not a realistic portrayalCorrect Answer:  Not a realistic portrayal

Not a realistic portrayal

Question 6: Multiple Choice

-

Why were Thomas Edison's early films for the Kinetoscope rather limited?

Why were Thomas Edison's early films for the Kinetoscope rather limited?Given Answer:  Only one person at a time could view them

Only one person at a time could view themCorrect Answer:  Only one person at a time could view them

Only one person at a time could view them

Question 7: Multiple Choice

-

Why did early silent films appeal especially to the working-class, immigrant audiences?

Why did early silent films appeal especially to the working-class, immigrant audiences?Given Answer:  They didn't have to understand English

They didn't have to understand EnglishCorrect Answer:  They didn't have to understand English

They didn't have to understand English

Question 8: Multiple Choice

-

Why did The Birth of a Nation establish director D. W. Griffith as a film master?

Why did The Birth of a Nation establish director D. W. Griffith as a film master?Given Answer:  His use of cinematic space

His use of cinematic spaceCorrect Answer:  His use of cinematic space

His use of cinematic space

Question 9: Multiple Choice

-

What special significance does the spiral have in Cubist paintings such as Picasso's Violin?

What special significance does the spiral have in Cubist paintings such as Picasso's Violin?Given Answer:  The interplay between two and three dimensions

The interplay between two and three dimensionsCorrect Answer:  The interplay between two and three dimensions

The interplay between two and three dimensions

Question 10: Multiple Choice

Why was the Der Blaue Reiter artist Wassily Kandinsky obsessed with color?

|

|||||

| |||||

Pre-Built Course Content

https://blackboard.strayer.edu/bbcswebdav/institution/HUM/112/1146/Week7/Lecture/lecture.html

HUM112 Music Clips for Week 7

This week's music clips relate to chapters 33 and 34.

- Claude Debussy, Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune (="Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun") (chap. 33, pp. 1093-1094)

Read pp. 1092-1094 (in chap. 33) and then read the paragraphs below.

Once you do that, imagine yourself as a faun in a meadow on a sunny

day; click on the YouTube above, close your eyes and listen.

A faun (not to be confused with "fawn", which is a young deer) is a creature from ancient Greek and Roman mythology.

A faun is part goat and part human; it usually has the horns of a goat

but otherwise is human from head to waist, and is goat from waist to

feet. The ancients considered fauns as one type of forest deity among many. They were associated with lustful impulses, not having the constraints of formal urban society.

Debussy's musical composition was inspired by a major poem by his

friend Stéphane Mallarmé, a poem composed in French (1865; final version

in 1876) originally and going by the title L'Après-midi d'un faune (="The Afternoon of a Faun"). Edwards (http://history.hanover.edu/courses/excerpts/111mall.html) describes Mallarme's poem this way:

"....a

monologue told by the Faun himself, is loosely based on the myth of the

god Pan's attempt to seduce the beautiful nymph Syrinx. (Fauns and

nymphs are minor forest deities in ancient mythology.) In the myth, just

as Pan had caught and embraced Syrinx, fellow nymphs came to her rescue

and magically turned her into a sheaf of reeds. In his sigh of regret

at losing Syrinx, Pan breathes air into the reeds and discovers the

beauty of music. Mallarme's poem does not follow the same story-line as

the original myth, but his faun does attempt to seduce nymphs, he does

play music, and he is frustrated from realizing his goal (though this is

left ambiguous). The poem begins with the faun waking up from a dream

and ends with him falling asleep, wine by his side, to return to his

dreams. In between he tells of his efforts to seduce fauns, though it is

never entirely clear whether and when he is describing real events,

memories, or dreams."

See this major SYMBOLIST poem in English translation on p. 1093 (in chap. 33), but for a more complete translation see http://web.fscj.edu/Joy.Kairies/tutorials_2012/chapter32_tut/Impressionism/Mallarme/mallarme.html . For French text with translation, see http://www.ancientsites.com/aw/Article/1262762. On symbolist poetry, see pp. 1091-1093, and also http://www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/cas/fnart/symbolist/symbolist_intro.html.

Back to Debussy's work, Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune: As

you listen to Debussy's work, think of it illustrating the moods and

lustful fantasies of a faun on a hot afternoon. Debussy's composition

later inspired a ballet based on this same poem.

1.b. Claude Debussy, La Mer (="The Sea") (chap. 33, p. 1094)

Read

carefully in 1094 (in chap. 33) about the three sections of this work;

consider the book's description of this as "Impressionist" music (the

analogy being to Impressionist paintings); but also consider the

suggestion the it might be "Symbolist" and reflect on the differences

described between the two.

The book describes the three parts of this--light on the surface of the

water, movement of waves, and sound of wind on the water. Feel free to listen to a few minutes and then fast forward to the different parts.

1.c. Claude Debussy, Clair de lune (not mentioned in book; Debussy is on pp. 1093-1094, 1179)

Claude Debussy composed this famous work as the third movement of a piano suite entitled Suite Bergamasque. "Clair de lune" is French for "moonlight". It was completed in 1905. For some it evokes the image and mood of moonlight shining through the leaves of a tree. It seems to have been inspired by a symbolist French poem (also entitled Claire de lune) by Paul Verlaine, penned in 1869. For the French text and translation of the poem, see http://www.press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/853446.html ; scroll down to the second poem . For one person's experience playing Debussy's composition, see http://blog.thecurrent.org/2012/08/debussys-150th-birthday-spirit-his-clair-de-lune-lives/.

--------------------

- Gustav Mahler, Symphony No. 1, 3rd Movement (chap. 33, p. 1104-1105)

Read carefully the description of this piece on p. 1104 (in chap. 33). Mahler was a prominent composer from Vienna in the late 1800s.

2.b. Gustav Mahler, Symphony No. 2 (=The Resurrection Symphony"), in full (not mentioned in book) If truly ambitious, listen to this long but marvelous symphony.

For background, see http://www.kennedy-center.org/calendar/?fuseaction=composition&composition_id=2484.

-------------------------------

- Johannes Brahms, Symphony No. 4, 4th Movement (chap. 33, pp. 1104-1105)

Read carefully pp. 1104-1105 (in chap. 33). This was composed in 1885. Our class text notes that it is marked allegro energico e passionato (energetically fast and passionate).

----------------------------------

- Igor Stravinsky, Le Sacre de printemps (=The Rite of Spring) (chap. 34, pp. 1129-1130)

Read carefully pp. 1129-1130 (in chap. 34) on this ballet, for which Stravinsky composed the music and Nijinsky did the choreography. (Compare Debussy's work--number 1 above; pp. 1093-4; note how this is another twist on Mallarme's poem--a ballet with new music). It is very interesting to consider audience expectations for any performance.

It is a my guess that most of you will listen to this music and find it

enjoyable and inventive with all the tempo changes, certainly nothing

to complain about.

And the dance and choreography will seem good and tame (there are more

erotic modern dance versions of this, but this is the more conservative

original). Yet, in 1913, early in the performance there was so much

hissing and booing--apparently directed at the music, not the dance--that "police had to be called, as Stravinsky himself crawled to safety out a backstage window" (p. 1129)!!!! I guess this is a different version of "Elvis has left the building"!

-------------------------

- Arnold Schoenberg, "Madonna" , section 6 in Pierrot Lunaire (chap. 34, p. 1133)

-

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=INMo2Tg8fqc For German lyrics and English translation, see http://www.lunanova.org/pierrot/text.html and scroll down to number 6.

Read carefully p. 1133 (in chap. 34). Schoenberg completed this work in 1912. Realize that this is deliberately atonal (He would say "pantonal"). Note the use of Sprechstimme (="speech song") instead of normal singing and Schoenberg's description of this.

Pierrot is the name of the main character, who is a clown by

profession. "Pierrot Lunaire" can be translated "Moonstruck Pierrot" or

"Pierrot in the Moonlight". Pierrot Lunaire is a work made up of 21 poems or songs, though actually they are put into three groups of 7 songs each. The subject matter of each 13-line poem is quite varied.

This song called "Madonna" is a song to Mary when she is holding her

son Jesus after he is taken down from the cross, the moment captured

most famously in Michelangelo's sculpture called The Pietà.

(There is no scriptural account of this event, though it cannot be

discounted as a possibility. It became a common motif in tradition and

art.) There is an allusion to a figurative warning Mary received in Luke

2:35 that "a sword shall pierce your own soul".

This song "Madonna" graphically captures the moment as Mary "the mother

of sorrows" cradles her dead son in her arms. Read the text of the

lyrics at the link above.

------------------------------------

- Giacomo Puccini, "Un bel di" from Madama Butterfly (chap. 34, p. 1133)

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s_L0m1vYrmk&list=PL27A752E13BEBF364&index=16

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1woH96ROG-c (two versions) For text and translation, see http://classicalmusic.about.com/od/opera/qt/unbeldilyrics.htm .

Puccini completed and first presented this opera in 1904. The story in this opera was roughly based on stories that had appeared in a play and short story in the late 1800s. Read carefully p. 1133 (in chap. 34)

for a brief summary of the story of an irresponsible American sailor

who abandoned his bride (Cio-Cio-San, meaning Butterfly) and returned to

America. It is a tragic, heart-wrenching story. Un bel di (= "One Fine Day") is the play's most famous aria. It is sung in Act 2. It shows her longing for her husband's return one day, and she fantasizes about that event. But, the audience suspects that, deep down, this is an attempt to convince herself of that.

---------------------------------

6.b. Giacomo Puccini, "Nessun dorma" from Turandot (chap. 34, pp. 1133-1134)

-

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rTFUM4Uh_6Y See Italian text with translation at http://www.wowzone.com/vincero.htm .

This opera by Puccini was composed primarily by Puccini, though he died in 1924 before it was finished.

Alfano completed the work, and it was first performed in 1926. This

opera was based on plays of the story that had appeared in various

versions for several centuries before.

In the opera, the story is set in ancient Peking (now called Beijing,

China) where the a cold-hearted and cruel princess named Turandot is

dealing with a suitor named Prince Calàf. The story is nicely summarized

on pp. 1133-1134 (in chap. 34).

She does not want to marry him, but he has answered her riddles and

challenges. Realizing her dilemma, he offered to forfeit his life at

dawn if she could discover his real name. Thus,

by Act III, she is determined that no one is the town shall sleep until

she gets the name (she preferred he die than that she marry him). Thus, the aria, Nessun dorma ("Let No One Sleep").

---------------------------------------------

Week 7 Explore

Debussy and Mahler

Kandinsky's Effect: Reflections on Synesthetic Lesson in Abstraction, 7:22

When Wassily Kandinsky introduced his theory in art composition in the 1920s, his method of abstraction was perceived as objective and universal resulting in a learned language believed to be able to communicate universally. As historians have asserted that Kandinsky's theory was influenced by his genuine synesthesia experience, the method can also be viewed as subjective. Therefore, objective teaching and critique of abstraction often raises controversies due to the perceived universal quality. In this light, this paper proposes a quasi-experimental study based on a small cross-modality experiment conducted by Kandinsky in order to gain insight understanding in abstraction lesson design. In this study, 30 students are randomly divided into two groups, one with single-modality method of learning another with synesthetic or cross-modality method of learning based on Kandinsky's synesthetic paintings. In the cross-modality method, students immerse themselves into the paintings by creating sound samples from percussion instruments, which are then blindly assigned to other students in the same group to compose three dimensional models that best depict the sound samples. Findings are presented in a narrative amalgamation in order to provide an understanding in advantages and disadvantages of single-modality method (objective-based lesson) and cross-modality method (subjective-based, synesthetic lesson) in abstraction. (By: Chutarat Laomanacharoen, Assumption University)

https://youtu.be/Z0GtwbgaQXY

- Chapter 33 (p. 1092-4), Debussy; (pp. 1104-1105), Mahler; review the Week 7 “Music Folder”

- “Approaching Mahler and Debussy” – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QYZ1mUupG7k

- Musical selections for Mahler – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RONBzkthUjM (Symphony No. 2, Finale; Resurrection Symphony) or http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kbRyttzUzjI (Symphony No. 1, 3rd Movement).

- Musical selection for Debussy – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EvnRC7tSX50 (Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune)

Kandinsky's Effect: Reflections on Synesthetic Lesson in Abstraction, 7:22

When Wassily Kandinsky introduced his theory in art composition in the 1920s, his method of abstraction was perceived as objective and universal resulting in a learned language believed to be able to communicate universally. As historians have asserted that Kandinsky's theory was influenced by his genuine synesthesia experience, the method can also be viewed as subjective. Therefore, objective teaching and critique of abstraction often raises controversies due to the perceived universal quality. In this light, this paper proposes a quasi-experimental study based on a small cross-modality experiment conducted by Kandinsky in order to gain insight understanding in abstraction lesson design. In this study, 30 students are randomly divided into two groups, one with single-modality method of learning another with synesthetic or cross-modality method of learning based on Kandinsky's synesthetic paintings. In the cross-modality method, students immerse themselves into the paintings by creating sound samples from percussion instruments, which are then blindly assigned to other students in the same group to compose three dimensional models that best depict the sound samples. Findings are presented in a narrative amalgamation in order to provide an understanding in advantages and disadvantages of single-modality method (objective-based lesson) and cross-modality method (subjective-based, synesthetic lesson) in abstraction. (By: Chutarat Laomanacharoen, Assumption University)

https://youtu.be/Z0GtwbgaQXY

- Chapters 33 and 34, works by Van Gogh, Seurat, Cezanne, Gauguin, Munch, Picasso, Braque, and Matisse

- New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Search names listed above at http://www.moma.org/collection/artist_index.php?start_initial=A&end_initial=A&unparsed_search=2

A child-friendly introduction to Vincent van Gogh. Who was he? Why is he famous? What did he do? FreeSchool is great for kids!

Music: Jaunty Gumption, Running Fanfare, Gymnopedie no. 1 - Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com)

https://youtu.be/qv8TANh8djI

33 The Fin de Siècle

Fin de siècle (French pronunciation: [fɛ̃ də sjɛkl]) is French for end of the century, a term which typically encompasses both the meaning of the similar English idiom turn of the century and also makes reference to the closing of one era and onset of a new era. The term is typically used to refer to the end of the 19th century. This period was widely thought to be a period of degeneration, but at the same time a period of hope for a new beginning.[1] The "spirit" of fin de siècle often refers to the cultural hallmarks that were recognized as prominent in the 1880s and 1890s, including ennui, cynicism, pessimism, and "...a widespread belief that civilization leads to decadence."[2]

The term "fin de siècle" is commonly applied to French art and artists, as the traits of the culture first appeared there, but the movement affected many European countries.[3] The term becomes applicable to the sentiments and traits associated with the culture, as opposed to focusing solely on the movement's initial recognition in France. The ideas and concerns developed by fin de siècle artists provided the impetus for movements such as symbolism and modernism.[4]

The themes of fin de siècle political culture were very controversial and have been cited as a major influence on fascism[5][6] and as a generator of the science of geopolitics, including the theory of lebensraum.[7][8] The major political theme of the era was that of revolt against materialism, rationalism, positivism, bourgeois society, and liberal democracy.[5] The fin-de-siècle generation supported emotionalism, irrationalism, subjectivism, and vitalism,[6] while the mindset of the age saw civilization as being in a crisis that required a massive and total solution.[5]

Degeneration theory

-

B. A. Morel's Degeneration theory holds that although societies can progress, they can also remain static or even regress if influenced by a flawed environment, such as national conditions or outside cultural influences.[9] This degeneration can be passed from generation to generation, resulting in imbecility and senility due to hereditary influence. Max Nordau's Degeneration holds that the two dominant traits of those degenerated in a society involve ego mania and mysticism.[9] The former term was understood to mean a pathological degree of self-absorption and unreasonable attention to one's own sentiments and activities, as can be seen in the extremely descriptive nature of minute details; the latter referred to the impaired ability to translate primary perceptions into fully developed ideas, largely noted in symbolist works.[10] Nordau's treatment of these traits as degenerative qualities lends to the perception of a world falling into decay through fin de siècle corruptions of thought, and influencing the pessimism growing in Europe's philosophical consciousness.[9]

As fin de siècle citizens, attitudes tended toward science in an attempt to decipher the world in which they lived. The focus on psycho-physiology, now psychology, was a large part of fin de siècle society[11] in that it studied a topic that could not be depicted through Romanticism, but relied on traits exhibited to suggest how the mind works, as does symbolism. The concept of genius returned to popular consciousness around this period through Max Nordau's work with degeneration, prompting study of artists supposedly affected by social degeneration and what separates imbecility from genius. The genius and the imbecile were determined to have largely similar character traits, including les delires des grandeurs and la folie du doute.[9] The first, which means delusions of grandeur, begins with a disproportionate sense of importance in one's own activities and results in a sense of alienation,[12] as Nordau describes in Baudelaire, as well as the second characteristic of madness of doubt, which involves intense indecision and extreme preoccupation to minute detail.[9] The difference between degenerate genius and degenerate madman become the extensive knowledge held by the genius in a few areas paired with a belief in one's own superiority as a result. Together, these psychological traits lend to originality, eccentricity, and a sense of alienation, all symptoms of la mal du siècle that impacted French youth at the beginning of the 19th century until expanding outward and eventually influencing the rest of Europe approaching the turn of the century.[12][13]

The Belgian symbolist Fernand Khnopff's The CaressPessimism

England's ideological space was affected by the philosophical waves of pessimism sweeping Europe, starting with philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer's work from before 1860 and gradually influencing artists internationally.[13] R. H. Goodale identified 235 essays by British and American authors concerning pessimism, ranging from 1871 to 1900, showing the prominence of pessimism in conjunction with English ideology.[13] Further, Oscar Wilde's references to pessimism in his works demonstrate the relevance of the ideology on the English. In An Ideal Husband, Wilde's protagonist asks another character whether "at heart, [she is] an optimist or a pessimist? Those seem to be the only two fashionable religions left to us nowadays."[13] Wilde's reflection on personal philosophy as more culturally significant than religion lends credence to the Degeneration Theory, as applied to Baudelaire's influence on other nations.[9] However, the optimistic Romanticism popular earlier in the century would also have had an impact on the shifting ideological landscape. The newly fashionable pessimism appears again in Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest, written that same year:

Lane is philosophically current as of 1895, reining in his master's optimism about the weather by reminding Algernon of how the world typically operates. His pessimism gives satisfaction to Algernon; the perfect servant of a gentleman is one who is philosophically aware.[13] Charles Baudelaire's work demonstrates some of the pessimism expected of the time, and his work with modernity exemplified the decadence and decay with which turn-of-the-century French art is associated, while his work with symbolism promoted the mysticism Nordau associated with fin de siècle artists. Baudelaire's pioneering translations of Edgar Allan Poe's verse supports the aesthetic role of translation in fin de siècle culture,[14] while his own works influenced French and English artists through the use of modernity and symbolism. Baudelaire influenced other French artists like Arthur Rimbaud, the author of René whose titular character displays the mal du siècle that European youths of the age displayed.[13] Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and their contemporaries became known as French decadents, a group that influenced its English counterpart, the aesthetes like Oscar Wilde. Both groups believed the purpose of art was to evoke an emotional response and demonstrate the beauty inherent in the unnatural as opposed to trying to teach its audience an infallible sense of morality.[15]Algernon: I hope tomorrow will be a fine day, Lane.

Lane: It never is, sir.

Algernon: Lane, you're a perfect pessimist.

Lane: I do my best to give satisfaction, sir.

Artistic conventions

The works of the Decadents and the Aesthetes contain the hallmarks typical of fin de siècle art. Holbrook Jackson's The Eighteen Nineties describes the characteristics of English decadence, which are: perversity, artificiality, egoism, and curiosity.[10]

At the Moulin Rouge (1895), a painting by Henri Toulouse-Lautrec that captures the vibrant and decadent spirit of society during the fin de siècle

The first trait is the concern for the perverse, unclean, and unnatural.[9] Romanticism encouraged audiences to view physical traits as indicative of one's inner self, whereas the fin de siècle artists accepted beauty as the basis of life, and so valued that which was not conventionally beautiful.[10]

This belief in beauty in the abject leads to the obsession with artifice and symbolism, as artists rejected ineffable ideas of beauty in favour of the abstract.[10] Through symbolism, aesthetes could evoke sentiments and ideas in their audience without relying on an infallible general understanding of the world.[12]

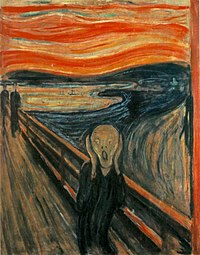

The Scream (1893), an expressionist painting by Edvard Munch is a prominent cultural symbol of fin de siècle era.[16]

The third trait of the culture is egoism, a term similar to that of ego-mania, meaning disproportionate attention placed on one's own endeavours. This can result in a type of alienation and anguish, as in Baudelaire's case, and demonstrates how aesthetic artists chose cityscapes over country as a result of their aversion to the natural.[9]

Finally, curiosity is identifiable through diabolism and the exploration of the evil or immoral, focusing on the morbid and macabre, but without imposing any moral lessons on the audience.[10][15]

Fin-de-siècle Vienna Top #7 Facts, 1:25

https://youtu.be/PtX4Sem3nYE

TOWARD THE MODERN 1085

The Paris Exposition of 1889 1086

The Exposition Universelle of 1889 was a world's fair held in Paris, France, from 6 May to 31 October 1889.

It was held during the year of the 100th anniversary of the storming of the Bastille, an event considered symbolic of the beginning of the French Revolution. The fair included a reconstruction of the Bastille and its surrounding neighborhood, but with the interior courtyard covered with a blue ceiling decorated with fleur-de-lys and used as a ball room and gathering place.[1]

The 1889 Exposition covered a total area of 0.96 km2, including the Champ de Mars, the Trocadéro, the quai d'Orsay, a part of the Seine and the Invalides esplanade. Transport around the Exposition was partly provided by a 3 kilometre (1.9 mi) 600 millimetre (2 ft 0 in) gauge railway by Decauville. It was claimed that the railway carried 6,342,446 visitors in just six months of operation. Some of the locomotives used on this line later saw service on the Chemins de Fer du Calvados.[2]

Paris 1889 World's Fair, 3:51

This video is a compilation of photographs from the U.S. Library of Congress archives of the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle, or the Paris World's Fair.

https://youtu.be/A9BsHPqasak

The Fin de Siècle: From Naturalism to Symbolism 1087

Realism

Realism in the arts is the attempt to represent subject matter truthfully, without artificiality and avoiding artistic conventions, implausible, exotic and supernatural elements.

Realism has been prevalent in the arts at many periods, and is in large part a matter of technique and training, and the avoidance of stylization. In the visual arts, illusionistic realism is the accurate depiction of lifeforms, perspective, and the details of light and colour. Realist works of art may emphasize the mundane, ugly or sordid, such as works of social realism, regionalism, or kitchen sink realism.

There have been various realism movements in the arts, such as the opera style of verismo, literary realism, theatrical realism and Italian neorealist cinema. The realism art movement in painting began in France in the 1850s, after the 1848 Revolution.[1] The realist painters rejected Romanticism, which had come to dominate French literature and art, with roots in the late 18th century.

Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet, 1854. A Realist painting by Gustave Courbet

Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet, 1854. A Realist painting by Gustave Courbet What's the Difference Between Realism & Naturalism? #withcaptions | ARTiculations,

Betty explains the difference between the art movement realism and the art style naturalism. 4:32

https://youtu.be/ofxkDCSxDMU

Naturalism

Naturalism introduction, 5:14

https://youtu.be/M91epmOsMWU

Symbolism

Symbolism was a late nineteenth-century art movement of French, Russian and Belgian origin in poetry and other arts. In literature, the style originates with the 1857 publication of Charles Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du mal. The works of Edgar Allan Poe, which Baudelaire admired greatly and translated into French, were a significant influence and the source of many stock tropes and images. The aesthetic was developed by Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine during the 1860s and 1870s. In the 1880s, the aesthetic was articulated by a series of manifestos and attracted a generation of writers. The name "symbolist" itself was first applied by the critic Jean Moréas, who invented the term to distinguish the symbolists from the related decadents of literature and of art.

Distinct from, but related to, the style of literature, symbolism of art is related to the gothic component of Romanticism.

Impressionism, Post Impressionism, Symbolism Movements in Art, 5:49

This is a video about three movements of art that changed the art world. This video is for educational purposes only.

https://youtu.be/hZ3SV86dNeU

Art Nouveau 1087

Art Nouveau (French pronunciation: [aʁ nuvo], Anglicised to /ˈɑːrt nuːˈvoʊ/; Austria. Sezession or Secessionsstil, Catalan Modernisme, Czech Secese, English Modern Style, Germany Jugendstil or Reformstil, Italian also Stile Floreale or Liberty, Slovak Secesia, Russian Модерн [Modern]) or Jugendstil is an international philosophy[1] and style of art, architecture and applied art – especially the decorative arts – that was most popular during 1890–1910.[2] English uses the French name Art Nouveau ("new art"), but the style has many different names in other countries. A reaction to academic art of the 19th century, it was inspired by natural forms and structures, not only in flowers and plants, but also in curved lines. Architects tried to harmonize with the natural environment.[3]

Art Nouveau is considered a "total" art style, embracing architecture, graphic art, interior design, and most of the decorative arts including jewellery, furniture, textiles, household silver and other utensils and lighting, as well as the fine arts. According to the philosophy of the style, art should be a way of life. For many well-off Europeans, it was possible to live in an art nouveau-inspired house with art nouveau furniture, silverware, fabrics, ceramics including tableware, jewellery, cigarette cases, etc. Artists desired to combine the fine arts and applied arts, even for utilitarian objects.[3]

Although Art Nouveau was replaced by 20th-century Modernist styles,[4] it is now considered as an important transition between the eclectic historic revival styles of the 19th century and Modernism.[5]

Art Nouveau - Overview - Goodbye-Art Academy, 5:08

This is an overview of Art Nouveau a movement in Art History from 1890-1910.

https://youtu.be/P4luPnObQYo

Exposing Society’s Secrets: The Plays of Henrik Ibsen 1089

Henrik Johan Ibsen (/ˈɪbsən/;[1] Norwegian: [ˈhɛnɾɪk ˈɪpsən]; 20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) was a major 19th-century Norwegian playwright, theatre director, and poet. He is often referred to as "the father of realism" and is one of the founders of Modernism in theatre.[2] His major works include Brand, Peer Gynt, An Enemy of the People, Emperor and Galilean, A Doll's House, Hedda Gabler, Ghosts, The Wild Duck, Rosmersholm, and The Master Builder. He is the most frequently performed dramatist in the world after Shakespeare,[3][4] and A Doll's House became the world's most performed play by the early 20th century.[5]

Several of his later dramas were considered scandalous to many of his era, when European theatre was expected to model strict morals of family life and propriety. Ibsen's later work examined the realities that lay behind many façades, revealing much that was disquieting to many contemporaries. It utilized a critical eye and free inquiry into the conditions of life and issues of morality. The poetic and cinematic early play Peer Gynt, however, has strong surreal elements.[6]

Ibsen is often ranked as one of the most distinguished playwrights in the European tradition.[7] Richard Hornby describes him as "a profound poetic dramatist—the best since Shakespeare".[8] He is widely regarded as the most important playwright since Shakespeare.[7][9] He influenced other playwrights and novelists such as George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, Arthur Miller, James Joyce, Eugene O'Neill and Miroslav Krleža. Ibsen was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1902, 1903 and 1904.[10]

Ibsen wrote his plays in Danish (the common written language of Denmark and Norway)[11] and they were published by the Danish publisher Gyldendal. Although most of his plays are set in Norway—often in places reminiscent of Skien, the port town where he grew up—Ibsen lived for 27 years in Italy and Germany, and rarely visited Norway during his most productive years. Born into a merchant family connected to the patriciate of Skien, Ibsen shaped his dramas according to his family background. He was the father of Prime Minister Sigurd Ibsen. Ibsen's dramas continue in their influence upon contemporary culture and film with notable film productions including A Doll's House featuring Jane Fonda and A Master Builder featuring Wallace Shawn.

A Short History Of Henrik Ibsen, 4:15

A more serious, yet slightly humerous video, featuring the history of a very important man to our world's history in writing, Henrik Ibsen.

https://youtu.be/CAxGNj83WQ0

The Symbolist Imagination in the Arts 1090

Symbolism was a late nineteenth-century art movement of French, Russian and Belgian origin in poetry and other arts.

Symbolism and fin de siecle painting, 7:20

I close out the 19th century with a look at the symbolists and the Viennese Secession school as represented by Gustav Klimt.

https://youtu.be/OQLGYJ0zEoc

Post-Impressionist Painting 1094

Post-Impressionism (also spelled Postimpressionism) is a predominantly French art movement that developed roughly between 1886 and 1905; from the last Impressionist exhibition to the birth of Fauvism. Post-Impressionism emerged as a reaction against Impressionists’ concern for the naturalistic depiction of light and colour. Due to its broad emphasis on abstract qualities or symbolic content, Post-Impressionism encompasses Neo-Impressionism, Symbolism, Cloisonnism, Pont-Aven School, and Synthetism, along with some later Impressionists' work. The movement was led by Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, and Georges Seurat.

The term Post-Impressionism was first used by art critic Roger Fry in 1906.[1][2] Critic Frank Rutter in a review of the Salon d'Automne published in Art News, 15 October 1910, described Othon Friesz as a "post-impressionist leader"; there was also an advert for the show The Post-Impressionists of France.[3] Three weeks later, Roger Fry used the term again when he organized the 1910 exhibition, Manet and the Post-Impressionists, defining it as the development of French art since Manet.

Post-Impressionists extended Impressionism while rejecting its limitations: they continued using vivid colours, often thick application of paint, and real-life subject matter, but were more inclined to emphasize geometric forms, distort form for expressive effect, and use unnatural or arbitrary colour.

What is Post Impressionism? 3:45

Brief description of post impressionism with some of the post impressionist artists.

https://youtu.be/fjkB4fRDnH8

Pointillism: Seurat and the Harmonies of Color 1095

Georges-Pierre Seurat (French: [ʒɔʁʒ pjɛʁ sœʁa];[1] 2 December 1859 – 29 March 1891) was a French post-Impressionist painter and draftsman. He is noted for his innovative use of drawing media and for devising the painting techniques known as chromoluminarism and pointillism. Seurat's artistic personality was compounded of qualities which are usually supposed to be opposed and incompatible. On the one hand, his extreme and delicate sensibility, on the other a passion for logical abstraction and an almost mathematical precision of mind.[2] His large-scale work, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884–1886), altered the direction of modern art by initiating Neo-impressionism, and is one of the icons of late 19th-century painting.[3]

Pointillism, 1:41

Can you guess the animal?

This is one of three short clips developed for a class taking part in International Dot Day promoting creativity around the world. It is celebrated on September 15 each year. The clip asks children to identify an animal. At first the large dots make it difficult but the dot size is gradually reduced until the image clears. Because of the rods and cones in our eyes, we really see dots. The more dots, the finer the picture.

https://youtu.be/QT5KtPoS-Tw

Georges Seurat, 3:33

The works of the pointillist Georges Seurat set to the music of V . . . ?

https://youtu.be/orjJmLwbnR0

Symbolic Color: Van Gogh 1096

Vincent Willem van Gogh Dutch: [ˈvɪnsɛnt ˈʋɪləm vɑn ˈɣɔx] ( listen);[note 1][1] (30 March 1853 – 29 July 1890) was a Dutch post-Impressionist painter whose work had far-reaching influence on 20th-century art. His output includes portraits, self portraits, landscapes, still lifes, olive trees and cypresses, wheat fields and sunflowers. Critics largely ignored his work until after his presumed suicide in 1890. His short life, expressive and spontaneous use of vivid colours, broad oil brushstrokes and emotive subject matter, mean he is recognisable in the public imagination as the quintessential misunderstood genius.

Van Gogh was born to religious upper middle class parents. He was driven as an adult by a strong sense of purpose, but was also thoughtful and intellectual; he was equally aware of modernist currents in art, music and literature. He was well travelled and spent several years in his 20s working for a firm of art dealers in The Hague, London and Paris, after which he taught in England at Isleworth and Ramsgate. He drew as a child, but spent years drifting in ill health and solitude, and did not paint until his late twenties. Most of his best-known works were completed during the last two years of his life. Deeply religious as a younger man, he worked from 1879 as a missionary in a mining region in Belgium where he sketched people from the local community. His first major work was 1885's The Potato Eaters, from a time when his palette mainly consisted of sombre earth tones and showed no sign of the vivid colouration that distinguished his later paintings. In March 1886, he moved to Paris and discovered the French Impressionists. Later, he moved to the south of France and was inspired by the region's strong sunlight. His paintings grew brighter in colour, and he developed the unique and highly recognisable style that became fully realised during his stay in Arles in 1888. In just over a decade, he produced more than 2,100 artworks, including around 860 oil paintings. After years of anxiety and frequent bouts of mental illness he died aged 37 from a self-inflicted gunshot wound. The extent to which his mental health affected his painting has been widely debated.

The widespread and popular realisation of his significance in the history of modern art began after his adoption by the early 20th-century German Expressionists and Fauves. Despite a widespread tendency to romanticise his ill health, art historians see an artist deeply frustrated by the inactivity and incoherence caused by frequent mental sickness. His posthumous reputation grew steadily; a romanticised version developed in the 20 years after his death when seen as an important but overlooked artist compared to other members of his generation. His reputation advanced with the emergence of the Fauvist movement in Europe and post WWII American respect for symbols of "heroic individualism" that was attractive to early US modernists and especially to the highly successful abstract expressionists of the 1950s; New York's MOMA launched major retrospectives early in the rehabilitation of his reputation, and made large acquisitions. By this stage his standing as a great artist and the romanticism of his life were firmly established.

The Sad Life of Vincent Van Gogh, 3:19

To all the people commenting that Vincent Van Gogh was shot by two kids is a proven fact, please don't - because it is only a theory. I understand that you're trying to help, but while I was researching for this video, I looked into it. Naifeh and Smith's theory has been met with a lot of skepticism and may even be a result of conclusion bias. So I decided to go along with the more accepted theory that he shot himself. In reality, no one knows what truly happened all those years ago. All we know is that a great painter was shot in the chest and it caused his death. On another note, I'm wearing a checkered tie and a pony shirt.

https://youtu.be/2RFcyAby4Nk

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2RFcyAby4Nk&feature=youtu.be

The Structure of Color: Cézanne 1097

Paul Cézanne (US /seɪˈzæn/ or UK /sᵻˈzæn/; French: [pɔl sezan]; 19 January 1839 – 22 October 1906) was a French artist and Post-Impressionist painter whose work laid the foundations of the transition from the 19th-century conception of artistic endeavour to a new and radically different world of art in the 20th century. Cézanne's often repetitive, exploratory brushstrokes are highly characteristic and clearly recognizable. He used planes of colour and small brushstrokes that build up to form complex fields. The paintings convey Cézanne's intense study of his subjects.

Cézanne is said to have formed the bridge between late 19th-century Impressionism and the early 20th century's new line of artistic enquiry, Cubism. Both Matisse and Picasso are said to have remarked that Cézanne "is the father of us all."

Paul Cézanne's Approach to Watercolor, 2:43

Learn how watercolors are made and Paul Cézanne's unique approach to the medium.

https://youtu.be/-Bykx5cBKMI

Escape to Far Tahiti: Gauguin 1099

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin (French: [øʒɛn ɑ̃ʁi pɔl ɡoɡɛ̃]; 7 June 1848 – 8 May 1903) was a French post-Impressionist artist. Underappreciated until after his death, Gauguin is now recognized for his experimental use of color and synthetist style that were distinctly different from Impressionism. His work was influential to the French avant-garde and many modern artists, such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. Gauguin's art became popular after his death, partially from the efforts of art dealer Ambroise Vollard, who organized exhibitions of his work late in his career, as well as assisting in organizing two important posthumous exhibitions in Paris.[1][2] Many of his paintings were in the possession of Russian collector Sergei Shchukin[3] as well as other important collections.

He was an important figure in the Symbolist movement as a painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramist, and writer. His bold experimentation with color led directly to the Synthetist style of modern art, while his expression of the inherent meaning of the subjects in his paintings, under the influence of the cloisonnist style, paved the way to Primitivism and the return to the pastoral. He was also an influential proponent of wood engraving and woodcuts as art forms.[4][5]

Paul Gauguin Paintings, 4:11

Paintings of the great master of painting Paul Gauguin. Paul Gauguin is a post-impressionist artists who was friend of Vincent Van Gogh. His paintings are from exotic places, painting landscapes and people, mostly of them Polynesian. http://www.allpaintings.org/v/Post-Im... This video is provided by www.allpaintings.org . Music: Polynesian Theme

https://youtu.be/h8OwzdRa2V0

The Late Monet 1102

Last years Monet, right, in his garden at Giverny, 1922 Failing sight

Monet's second wife, Alice, died in 1911, and his oldest son Jean, who had married Alice's daughter Blanche, Monet's particular favourite, died in 1914.[10] After Alice died, Blanche looked after and cared for Monet. It was during this time that Monet began to develop the first signs of cataracts.[48]

During World War I, in which his younger son Michel served and his friend and admirer Clemenceau led the French nation, Monet painted a series of weeping willow trees as homage to the French fallen soldiers. In 1923, he underwent two operations to remove his cataracts. The paintings done while the cataracts affected his vision have a general reddish tone, which is characteristic of the vision of cataract victims. It may also be that after surgery he was able to see certain ultraviolet wavelengths of light that are normally excluded by the lens of the eye; this may have had an effect on the colors he perceived. After his operations he even repainted some of these paintings, with bluer water lilies than before.[49]

Death

Monet died of lung cancer on 5 December 1926 at the age of 86 and is buried in the Giverny church cemetery.[41] Monet had insisted that the occasion be simple; thus only about fifty people attended the ceremony.[50]

His home, garden, and waterlily pond were bequeathed by his son Michel, his only heir, to the French Academy of Fine Arts (part of the Institut de France) in 1966. Through the Fondation Claude Monet, the house and gardens were opened for visits in 1980, following restoration.[51] In addition to souvenirs of Monet and other objects of his life, the house contains his collection of Japanese woodcut prints. The house and garden, along with the Museum of Impressionism, are major attractions in Giverny, which hosts tourists from all over the world.

CLAUDE MONET: Late Work at Gagosian Gallery West 21st Street, 3:44

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B1hPjb19fqY

Embedding disabled by request

Installation video of: "CLAUDE MONET: Late Work" May 1 - June 26, 2010 Gagosian Gallery West 21st Street, New York Featuring walk through with Paul Hayes Tucker Video shot by Trebuchet Interactive www.trebuchetweb.com If you would like to use this video, please contact newyork@gagosian.com

https://youtu.be/B1hPjb19fqY

Toward the Modern 1102

Existentialism is generally considered to be the philosophical and cultural movement which holds that the starting point of philosophical thinking must be the individual and the experiences of the individual. Building on that, existentialists hold that moral thinking and scientific thinking together do not suffice to understand human existence, and, therefore, a further set of categories, governed by the norm of authenticity, is necessary to understand human existence.[6][7][8]

Existential philosophers

- Søren Kierkegaard

- Friedrich Nietzsche

- Jean-Paul Sartre

- Simone de Beauvoir

- Karl Jaspers

- Gabriel Marcel

- Martin Heidegger

Explain Like I'm Five: Existentialism and Friedrich Nietzsche, 3:34

https://youtu.be/Kvz0CjtwH2k

The New Moral World of Nietzsche 1103

Does SCIENCE = TRUTH? (Nietzsche) - 8-Bit Philosophy, 3:07

http://youtu.be/Y68mGbvZZZg

Nietzsche

Simon Critchley Examines Friedrich Nietzsche,

The philosopher takes a look at Nietzsche's approach to life and death.

Critchley: Yeah. Nietzsche describes a mad man who runs into a public square shouting, God is dead. God is dead and the people didn't believe him, and he's laughed at, and he leaves. He came too soon. He says, he came, I came too soon. But the thought here is deeper, more interesting. It's not that the Nietzsche said, God is dead. Something you can find on _____ worlds, the world over is that God is dead, we have killed him, and what Nietzsche means by that I think is that the outcome of history is the death of God. We no longer need or we no longer can believe in those sorts of assurances which theology gave us through let's say, let's say through the development of science and technology. We've got ourselves to a position where God is an accessory that we can do without. So, it's not that Nietzsche was celebrating the death of God. He thinks that God is a pretty bad idea. He makes us cringing, cowardly, submissive creatures but it doesn't mean the opposite is something to be celebrated. We shouldn't just celebrate our, you know, that would lead to sort of annihilism. What Nietzsche thought is that, you know, human history is led to a point where we are, we find the idea of God incredible. We can no longer believe it and at that point he says, there's a risk of us throwing up our hands, and saying, well, nothing means anything. That's what Nietzsche calls annihilism. Nietzsche's thought is not annihilistic. This is a key thing. Nietzsche is trying to think, a counter movement to annihilism and this is what he calls a re-evaluation of values, or an overcoming of annihilism. It's what Nietzsche wants us to do. Nietzsche is, you know, Nietzsche wants us to reject our usual ways of thinking morally in terms of a new way of conceding of value that would be in terms of life ultimately, the affirmation of life, something like that.

Nihilism - life is without objective meaning, purpose, or intrinsic value.

http://youtu.be/MrI5WQ4u7MY

What basis for moral values and behavioral codes do we have (if not religion)?

The Big Bang Theory - Nietzsche on Morality, 1:42

http://youtu.be/1yydR6r7NNE

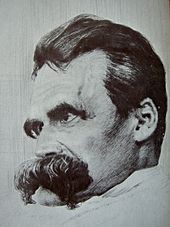

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (/ˈniːtʃə/;[3] German: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈvɪlhɛlm ˈniːt͡sʃə]; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, cultural critic, poet, and Latin and Greek scholar whose work has exerted a profound influence on Western philosophy and modern intellectual history.[4][5][6][7] Beginning his career as a classical philologist before turning to philosophy, he became the youngest-ever occupant of the Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel in 1869, at age 24. He resigned in 1879 due to health problems that plagued him most of his life, and he completed much of his core writing in the following decade.[8] In 1889, at age 44, he suffered a collapse and a complete loss of his mental faculties.[9] He lived his remaining years in the care of his mother (until her death in 1897) and then with his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, and died in 1900.[10]

Nietzsche's body of writing spanned philosophical polemics, poetry, cultural criticism, and fiction, and drew widely on art, philology, history, religion, and science. His writing displayed a fondness for aphorism and irony[11] while engaging with a wide range of subjects including morality, aesthetics, tragedy, epistemology, atheism, and consciousness. Some prominent elements of his philosophy include his radical critique of reason and truth in favor of perspectivism; his notion of the Apollonian and Dionysian; his genealogical critique of religion and Christian morality, and his related theory of master-slave morality;[4][12] his aesthetic affirmation of existence in response to the "death of God" and the profound crisis of nihilism;[4] and his characterization of the human subject as the expression of competing wills, collectively understood as the will to power.[13] In his later work, he developed influential concepts such as the Übermensch and the doctrine of eternal recurrence, and became increasingly preoccupied with the creative powers of the individual to overcome social, cultural, and moral contexts in pursuit of aesthetic health.[7]

After his death, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche became the curator and editor of her brother's manuscripts, reworking Nietzsche's unpublished writings to fit her own German nationalist ideology while often contradicting or obfuscating his stated opinions, which were explicitly opposed to antisemitism and nationalism. Through her published editions, Nietzsche's work became associated with fascism and Nazism;[14] 20th-century scholars contested this interpretation of his work and corrected editions of his writings were soon made available. His thought enjoyed renewed popularity in the 1960s, and his ideas have since had a profound impact on twentieth and early-twenty-first century thinkers across philosophy—especially in schools of continental philosophy such as existentialism, postmodernism, and post-structuralism—as well as art, literature, psychology, politics, and popular culture.[5][6][7][15][16]

Life

Youth (1844–69)

Born on 15 October 1844, Nietzsche grew up in the small town of Röcken, near Leipzig, in the Prussian Province of Saxony. He was named after King Frederick William IV of Prussia, who turned forty-nine on the day of Nietzsche's birth. (Nietzsche later dropped his middle name "Wilhelm".[17]) Nietzsche's parents, Carl Ludwig Nietzsche (1813–49), a Lutheran pastor and former teacher, and Franziska Oehler (1826–97), married in 1843, the year before their son's birth. They had two other children: a daughter, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, born in 1846, and a second son, Ludwig Joseph, born in 1848. Nietzsche's father died from a brain ailment in 1849; Ludwig Joseph died six months later, at age two.[18] The family then moved to Naumburg, where they lived with Nietzsche's maternal grandmother and his father's two unmarried sisters. After the death of Nietzsche's grandmother in 1856, the family moved into their own house, now Nietzsche-Haus, a museum and Nietzsche study centre.Nietzsche in 1861

In 1854, he began to attend Domgymnasium in Naumburg but since he showed particular talents in music and language, the internationally recognized Schulpforta admitted him as a pupil. He transferred and studied there from 1858 to 1864, becoming friends with Paul Deussen and Carl von Gersdorff. He also found time to work on poems and musical compositions. Nietzsche led "Germania," a music and literature club, during his summers in Naumburg.[19] At Schulpforta, Nietzsche received an important grounding in languages—Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and French—so as to be able to read important primary sources;[20] he also experienced for the first time being away from his family life in a small-town conservative environment. His end-of-semester exams in March 1864 showed a 1 in Religion and German; a 2a in Greek and Latin; a 2b in French, History, and Physics; and a "lackluster" 3 in Hebrew and Mathematics.[21]

While at Pforta, Nietzsche had a penchant for pursuing subjects that were considered unbecoming. He became acquainted with the work of the then almost-unknown poet Friedrich Hölderlin, calling him "my favorite poet" and composing an essay in which he said that the mad poet raised consciousness to "the most sublime ideality."[22] The teacher who corrected the essay gave it a good mark but commented that Nietzsche should concern himself in the future with healthier, more lucid, and more "German" writers. Additionally, he became acquainted with Ernst Ortlepp, an eccentric, blasphemous, and often drunken poet who was found dead in a ditch weeks after meeting the young Nietzsche but who may have introduced Nietzsche to the music and writing of Richard Wagner.[23] Perhaps under Ortlepp's influence, he and a student named Richter returned to school drunk and encountered a teacher, resulting in Nietzsche's demotion from first in his class and the end of his status as a prefect.[24]

Nietzsche in his younger days

"Hence the ways of men part: if you wish to strive for peace of soul and pleasure, then believe; if you wish to be a devotee of truth, then inquire..."[28]

Schopenhauer's philosophy strongly influenced Nietzsche's earliest philosophical thought.

In 1865, Nietzsche thoroughly studied the works of Arthur Schopenhauer. He owed the awakening of his philosophical interest to reading Schopenhauer's The World as Will and Representation and later admitted that Schopenhauer was one of the few thinkers whom he respected, dedicating to him the essay "Schopenhauer as Educator" in the Untimely Meditations.

In 1866, he read Friedrich Albert Lange's History of Materialism. Lange's descriptions of Kant's anti-materialistic philosophy, the rise of European Materialism, Europe's increased concern with science, Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, and the general rebellion against tradition and authority intrigued Nietzsche greatly. The cultural environment encouraged him to expand his horizons beyond philology and continue his study of philosophy,[citation needed] although Nietzsche would ultimately argue the impossibility of an evolutionary explanation of the human aesthetic sense.[30]

In 1867, Nietzsche signed up for one year of voluntary service with the Prussian artillery division in Naumburg. He was regarded as one of the finest riders among his fellow recruits, and his officers predicted that he would soon reach the rank of captain. However, in March 1868, while jumping into the saddle of his horse, Nietzsche struck his chest against the pommel and tore two muscles in his left side, leaving him exhausted and unable to walk for months.[31][32] Consequently, Nietzsche turned his attention to his studies again, completing them and meeting with Richard Wagner for the first time later that year.[33]

Professor at Basel (1869–78)

Mid-October 1871. From left: Erwin Rohde, Karl von Gersdorff, Nietzsche.

Despite the fact that the offer came at a time when he was considering giving up philology for science, he accepted.[35] To this day, Nietzsche is still among the youngest of the tenured Classics professors on record.[36]

Nietzsche's 1870 projected doctoral thesis, Contribution toward the Study and the Critique of the Sources of Diogenes Laertius (Beitrage zur Quellenkunde und Kritik des Laertius Diogenes), examined the origins of the ideas of Diogenes Laertius.[37] Though never submitted, it was later published as a Gratulationsschrift (congratulatory publication) at Basel.[38][39]

Before moving to Basel, Nietzsche renounced his Prussian citizenship: for the rest of his life he remained officially stateless.[40][41]

Nevertheless, Nietzsche served in the Prussian forces during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) as a medical orderly. In his short time in the military, he experienced much and witnessed the traumatic effects of battle. He also contracted diphtheria and dysentery.[citation needed] Walter Kaufmann speculates that he might also have contracted syphilis at a brothel along with his other infections at this time.[42][43] On returning to Basel in 1870, Nietzsche observed the establishment of the German Empire and Otto von Bismarck's subsequent policies as an outsider and with a degree of skepticism regarding their genuineness. His inaugural lecture at the university was "Homer and Classical Philology". Nietzsche also met Franz Overbeck, a professor of theology who remained his friend throughout his life. Afrikan Spir, a little-known Russian philosopher responsible for the 1873 Thought and Reality, and Nietzsche's colleague the famed historian Jacob Burckhardt, whose lectures Nietzsche frequently attended, began to exercise significant influence on him during this time.[44]

Nietzsche had already met Richard Wagner in Leipzig in 1868 and later Wagner's wife, Cosima. Nietzsche admired both greatly and, during his time at Basel, he frequently visited Wagner's house in Tribschen in Lucerne. The Wagners brought Nietzsche into their most intimate circle and enjoyed the attention he gave to the beginning of the Bayreuth Festival. In 1870, he gave Cosima Wagner the manuscript of "The Genesis of the Tragic Idea" as a birthday gift. In 1872, Nietzsche published his first book, The Birth of Tragedy. However, his colleagues within his field, including Ritschl, expressed little enthusiasm for the work, in which Nietzsche eschewed the classical philologic method in favor of a more speculative approach. In his polemic Philology of the Future, Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff dampened the book's reception and increased its notoriety. In response, Rohde (then a professor in Kiel) and Wagner came to Nietzsche's defense. Nietzsche remarked freely about the isolation he felt within the philological community and attempted unsuccessfully to transfer to a position in philosophy at Basel instead.

Nietzsche in c. 1872.

With the publication in 1878 of Human, All Too Human (a book of aphorisms ranging from metaphysics to morality to religion to gender studies), a new style of Nietzsche's work became clear, highly influenced by Afrikan Spir's Thought and Reality[45] and reacting against the pessimistic philosophy of Wagner and Schopenhauer. Nietzsche's friendship with Deussen and Rohde cooled as well. In 1879, after a significant decline in health, Nietzsche had to resign his position at Basel. (Since his childhood, various disruptive illnesses had plagued him, including moments of shortsightedness that left him nearly blind, migraine headaches, and violent indigestion. The 1868 riding accident and diseases in 1870 may have aggravated these persistent conditions, which continued to affect him through his years at Basel, forcing him to take longer and longer holidays until regular work became impractical.)

Independent philosopher (1879–88)

Living off his pension from Basel and aid from friends, Nietzsche travelled frequently to find climates more conducive to his health and lived until 1889 as an independent author in different cities. He spent many summers in Sils Maria near St. Moritz in Switzerland. He spent his winters in the Italian cities of Genoa, Rapallo, and Turin and the French city of Nice. In 1881, when France occupied Tunisia, he planned to travel to Tunis to view Europe from the outside but later abandoned that idea, probably for health reasons.[46] Nietzsche occasionally returned to Naumburg to visit his family, and, especially during this time, he and his sister had repeated periods of conflict and reconciliation.While in Genoa, Nietzsche's failing eyesight prompted him to explore the use of typewriters as a means of continuing to write. He is known to have tried using the Hansen Writing Ball, a contemporary typewriter device. In the end, a past student of his, Heinrich Köselitz or Peter Gast, became a sort of private secretary to Nietzsche. In 1876, Gast transcribed the crabbed, nearly illegible handwriting of Nietzsche for the first time with Richard Wagner in Bayreuth.[47] He subsequently transcribed and proofread the galleys for almost all of Nietzsche's work from then on. On at least one occasion on February 23, 1880, the usually broke Gast received 200 marks from their mutual friend, Paul Rée.[48] Gast was one of the very few friends Nietzsche allowed to criticize him. In responding most enthusiastically to Zarathustra, Gast did feel it necessary to point out that what were described as "superfluous" people were in fact quite necessary. He went on to list the number of people Epicurus, for example, had to rely on even to supply his simple diet of goat cheese.[49]

To the end of his life, Gast and Overbeck remained consistently faithful friends. Malwida von Meysenbug remained like a motherly patron even outside the Wagner circle. Soon Nietzsche made contact with the music-critic Carl Fuchs. Nietzsche stood at the beginning of his most productive period. Beginning with Human, All Too Human in 1878, Nietzsche would publish one book or major section of a book each year until 1888, his last year of writing; that year, he completed five.

Lou Salomé, Paul Rée and Nietzsche, 1882.

By 1882 Nietzsche was taking huge doses of opium but was still having trouble sleeping.[52] In 1883, while staying in Nice, he was writing out his own prescriptions for the sedative chloral hydrate, signing them "Dr. Nietzsche".[53]

After severing his philosophical ties with Schopenhauer (who was long dead and never met Nietzsche) and his social ties with Wagner, Nietzsche had few remaining friends. Now, with the new style of Zarathustra, his work became even more alienating and the market received it only to the degree required by politeness. Nietzsche recognized this and maintained his solitude, though he often complained about it. His books remained largely unsold. In 1885, he printed only 40 copies of the fourth part of Zarathustra and distributed only a fraction of these among close friends, including Helene von Druskowitz.

In 1883 he tried and failed to obtain a lecturing post at the University of Leipzig. It was made clear to him that, in view of his attitude towards Christianity and his concept of God, he had become effectively unemployable by any German university. The subsequent "feelings of revenge and resentment" embittered him: "And hence my rage since I have grasped in the broadest possible sense what wretched means (the depreciation of my good name, my character, and my aims) suffice to take from me the trust of, and therewith the possibility of obtaining, pupils."[54]

In 1886 Nietzsche broke with his publisher Ernst Schmeitzner, disgusted by his antisemitic opinions. Nietzsche saw his own writings as "completely buried and unexhumeable in this anti-Semitic dump" of Schmeitzner—associating the publisher with a movement that should be "utterly rejected with cold contempt by every sensible mind".[55] He then printed Beyond Good and Evil at his own expense. He also acquired the publication rights for his earlier works and over the next year issued second editions of The Birth of Tragedy, Human, All Too Human, Daybreak, and The Gay Science with new prefaces placing the body of his work in a more coherent perspective. Thereafter, he saw his work as completed for a time and hoped that soon a readership would develop. In fact, interest in Nietzsche's thought did increase at this time, if rather slowly and hardly perceptibly to him. During these years Nietzsche met Meta von Salis, Carl Spitteler, and Gottfried Keller.

In 1886, his sister Elisabeth also married the antisemite Bernhard Förster and travelled to Paraguay to found Nueva Germania, a "Germanic" colony—a plan Nietzsche responded to with mocking laughter.[56][not in citation given] Through correspondence, Nietzsche's relationship with Elisabeth continued through cycles of conflict and reconciliation, but they met again only after his collapse. He continued to have frequent and painful attacks of illness, which made prolonged work impossible.

In 1887 Nietzsche wrote the polemic On the Genealogy of Morals. During the same year, he encountered the work of Fyodor Dostoevsky, to whom he felt an immediate kinship.[57] He also exchanged letters with Hippolyte Taine and Georg Brandes. Brandes, who had started to teach the philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard in the 1870s, wrote to Nietzsche asking him to read Kierkegaard, to which Nietzsche replied that he would come to Copenhagen and read Kierkegaard with him. However, before fulfilling this promise, he slipped too far into illness. In the beginning of 1888, Brandes delivered in Copenhagen one of the first lectures on Nietzsche's philosophy.

Although Nietzsche had previously announced at the end of On The Genealogy of Morals a new work with the title The Will to Power: Attempt at a Revaluation of All Values, he eventually seems to have abandoned this idea and instead used some of the draft passages to compose Twilight of the Idols and The Antichrist in 1888.[58]

His health seemed to improve, and he spent the summer in high spirits. In the fall of 1888, his writings and letters began to reveal a higher estimation of his own status and "fate". He overestimated the increasing response to his writings, however, especially to the recent polemic, "The Case of Wagner". On his 44th birthday, after completing Twilight of the Idols and The Antichrist, he decided to write the autobiography Ecce Homo. In its preface—which suggests Nietzsche was well aware of the interpretive difficulties his work would generate—he declares, "Hear me! For I am such and such a person. Above all, do not mistake me for someone else".[59] In December, Nietzsche began a correspondence with August Strindberg and thought that, short of an international breakthrough, he would attempt to buy back his older writings from the publisher and have them translated into other European languages. Moreover, he planned the publication of the compilation Nietzsche Contra Wagner and of the poems that made up his collection Dionysian Dithyrambs.

Psychological illness and death (1889–1900)

Drawing by Hans Olde from the photographic series, The Ill Nietzsche, late-1899.

In the following few days, Nietzsche sent short writings—known as the Wahnzettel ("Madness Letters")—to a number of friends including Cosima Wagner and Jacob Burckhardt. Most of them were signed "Dionysos", though some were also signed "der Gekreuzigte" meaning "the crucified one". To his former colleague Burckhardt, Nietzsche wrote: "I have had Caiaphas put in fetters. Also, last year I was crucified by the German doctors in a very drawn-out manner. Wilhelm, Bismarck, and all anti-Semites abolished."[62] Additionally, he commanded the German emperor to go to Rome to be shot and summoned the European powers to take military action against Germany.[63]

The house Nietzsche stayed in while in Turin

(background, right), as seen from across Piazza Carlo Alberto, where he

is said to have had his breakdown. To the left is the rear façade of

the Palazzo Carignano.

In 1893, Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth returned from Nueva Germania in Paraguay following the suicide of her husband. She read and studied Nietzsche's works and, piece by piece, took control of them and their publication. Overbeck eventually suffered dismissal and Gast finally co-operated. After the death of Franziska in 1897, Nietzsche lived in Weimar, where Elisabeth cared for him and allowed visitors, including Rudolf Steiner (who in 1895 had written one of the first books praising Nietzsche),[64][page needed] to meet her uncommunicative brother. Elisabeth at one point went so far as to employ Steiner as a tutor to help her to understand her brother's philosophy. Steiner abandoned the attempt after only a few months, declaring that it was impossible to teach her anything about philosophy.[65]

Peter Gast would "correct" Nietzsche's writings after the philosopher's breakdown and did so without his approval.

In 1898 and 1899 Nietzsche suffered at least two strokes. This partially paralyzed him, leaving him unable to speak or walk. He likely suffered from clinical hemiparesis/hemiplegia on the left side of his body by 1899. After contracting pneumonia in mid-August 1900, he had another stroke during the night of 24–25 August and died at about noon on 25 August.[76] Elisabeth had him buried beside his father at the church in Röcken bei Lützen. His friend and secretary Gast gave his funeral oration, proclaiming: "Holy be your name to all future generations!"[77] Nietzsche had written in Ecce Homo (at that point still unpublished) of his fear that one day his name would be regarded as "holy".

Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche compiled The Will to Power from Nietzsche's unpublished notebooks and published it posthumously. Because his sister arranged the book based on her own conflation of several of Nietzsche's early outlines and took great liberties with the material, the scholarly consensus has been that it does not reflect Nietzsche's intent. (For example, Elisabeth removed aphorism 35 of The Antichrist, where Nietzsche rewrote a passage of the Bible.) Indeed, Mazzino Montinari, the editor of Nietzsche's Nachlass, called it a forgery.[78]

Citizenship, nationality, ethnicity