Two ten-minute breaks: 7:30 and 9 pm; Discussion 9:45, Dismiss, 10:15.

3 The Stability of Ancient Egypt FLOOD AND SUN 67

The Nile and Its Culture 68

Egyptian Religion: Cyclical Harmony 70

Pictorial Formulas in Egyptian Art 71

The Old Kingdom 74

The Stepped Pyramid at Saqqara 74

Three Pyramids at Giza 75

Monumental Royal Sculpture: Perfection and Eternity 78

The Sculpture of the Everyday 79

The Middle Kingdom at Thebes 81

Middle Kingdom Literature 81

Middle Kingdom Sculpture 81

The New Kingdom 83

Temple and Tomb Architecture and Their Rituals 83

Akhenaten and the Politics of Religion 87

The Return to Thebes and to Tradition 89

The Late Period, the Kushites, and the Fall of Egypt 91

The Kushites 92

Egypt Loses Its Independence 92

READINGS

3.1 from Memphis, “This It Is Said of Ptah” (ca. 2300 bce) 71

3.2 The Teachings of Khety (ca. 2040–1648 bce) 95

3.3 from Akhenaten’s Hymn to the Sun (14th century bce) 88

3.4 from a Book of Going Forth by Day 90

FEATURES

CONTEXT

Major Periods of Ancient Egyptian History 70

Some of the Principal Egyptian Gods 71

The Rosetta Stone 77

CLOSER LOOK Reading the Palette of Narmer 72

MATERIALS & TECHNIQUES Mummification 86

CONTINUITY & CHANGE Mutual Influence through Trade 93

4 The Aegean World and the Rise of Greece TRADE, WAR, AND VICTORY 97

The Cultures of the Aegean 97

The Cyclades 98

Minoan Culture in Crete 99

Mycenaean Culture on the Mainland 102

The Homeric Epics 105

The Iliad 107

The Odyssey 108

The Greek Polis 110

Behavior of the Gods 112

The Competing Poleis 113

The Sacred Sanctuaries 114

Male Sculpture and the Cult of the Body 118

Female Sculpture and the Worship of Athena 120

Athenian Pottery 121

The Poetry of Sappho 123

The Rise of Athenian Democracy 124

Toward Democracy: Solon and Pisistratus 124

Cleisthenes and the First Athenian Democracy 125

READINGS

4.1 from Homer, Iliad, Book 16 (ca. 750 bce) 128

4.1a from Homer, Iliad, Book 24 (ca. 750 bce) 108

4.2 from Homer, Odyssey, Book 9 (ca 725 bce) 130

4.2a from Homer, Odyssey, Book 4 (ca. 725 bce) 108

4.2b from Homer, Odyssey, Book 1 (ca. 725 bce) 109

4.3 from Hesiod, Works and Days (ca. 700 bce) 112

4.4 from Hesiod, Theogony (ca. 700 bce) 112

4.5 Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian Wars 113

4.6a–b Sappho, lyric poetry 124

4.7 from Aristotle’s Athenian Constitution 125

FEATURES

CONTEXT The Greek Gods 114

CLOSER LOOK The Classical Orders 116

CONTINUITY & CHANGE Egyptian and Greek Sculpture 126

Week 2 Explore

- Chapter 3 (pp. 86-8), Egyptian music

- Egyptian love poetry at http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/ancient/2000egypt-love.asp and http://www.humanistictexts.org/egyptlov.htm [not found]; as in the Old Testament’s “Song of Solomon,” the terms “brother” and “sister” are terms of affection and do not refer to a biological relationship

- Chapter 3 (pp. 74-5, 86, 89-91), Egyptian mummification and beliefs about afterlife

- Egyptian mummification and burial at http://www.ancientegypt.co.uk/mummies/explore/main.html

- Atlanta Michael Carlos Museum at http://carlos.emory.edu/COLLECTION/EGYPT/egypt01.html

- Egyptologist explains mummification at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ancient/afterlife-ancient-egypt.html

Ancient Greek Athletics and Female Status

- Chapter 4 (p. 118), Olympics. Chapters 4 (pp. 113-114), women in Sparta; For Athens later, see pp. 137-8.

- British Museum’s Running Girl artifact at http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/gr/b/bronze_figure_of_a_girl.aspx

- Philadelphia’s Penn Museum on Women and Greek athletics at http://www.penn.museum/sites/olympics/olympicsexism.shtml

HUM111 Music for Week 2

How The Rosetta Stone Unlocked Hieroglyphics, 2:45

Thanks to the British Museum! Go help choose their first YouTube series: https://youtu.be/luXVd6M-wQM The Rosetta Stone is one of the most famous archaeological finds in history: and it was the key to cracking Egyptian hieroglyphics. And while it took scholars years to work it out, there was one clue in there that helped unlock everything that followed. After hours in the British Museum, I went to explain...

https://youtu.be/yeQ-6eyMQ_o

Egyptian Mummification Process, 3:33

Takes students through the actual steps of mummification and gives visuals.

https://youtu.be/WBlwUM9uFes

2:45

- The Nile and its Culture

- The Old Kingdom

- The Middle Kingdom at Thebes

- The New Kingdom

- The Late Period, the Kushites, and the Fall of Egypt

https://youtu.be/KvgplApUIRE

Thinking Ahead

History and Civilization in Cyclades, 7:57

The name "Cyclades" derives from the islands that form a circle ("kyklos" in Greek) around the sacred island of Delos, in the Aegean Sea. Greek mythology mentions that the Cyclades were created by Poseidon, which transfigured the Nymphs Cyclades into islets when they angered him. The Cycladic civilization flourished in the 3rd millennium BC, mostly because of the strategic geographical position of the island complex as well as of their mineral richness.

Every island presents its special characteristics and its own beauty; however, all of them share the fascinating coexistence of blue and white in the Cycladic architecture, the endless sandy beaches, the rocky landscapes the traditional settlements, the blue color of the sky and the Aegean Sea, the wind and the blinding sunshine.

https://youtu.be/umNf888sVc8

The significant Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Cycladic culture is best known for its schematic flat female idols carved out of the islands' pure white marble centuries before the great Middle Bronze Age ("Minoan") culture arose in Crete, to the south. These figures have been stolen from burials to satisfy the Cycladic antiquities market since the early 20th century. Only about 40% of the 1,400 figurines found are of known origin, since looters destroyed evidence of the rest.

A distinctive Neolithic culture amalgamating Anatolian and mainland Greek elements arose in the western Aegean before 4000 BC, based on emmer wheat and wild-type barley, sheep and goats, pigs, and tuna that were apparently speared from small boats (Rutter). Excavated sites include Saliagos and Kephala (on Keos), which showed signs of copper-working. Each of the small Cycladic islands could support no more than a few thousand people, though Late Cycladic boat models show that fifty oarsmen could be assembled from the scattered communities (Rutter). When the highly organized palace-culture of Crete arose, the islands faded into insignificance, with the exception of Delos, which retained its archaic reputation as a sanctuary through the period of Classical Greek civilization (see Delian League).

The chronology of Cycladic civilization is divided into three major sequences: Early, Middle and Late Cycladic. The early period, beginning c. 3000 BC segued into the archaeologically murkier Middle Cycladic c. 2500 BC. By the end of the Late Cycladic sequence (c. 2000 BC) there was essential convergence between Cycladic and Minoan civilization.

There is some tension between the dating systems used for Cycladic civilization, one "cultural" and one "chronological". Attempts to link them lead to varying combinations; the most common are outlined below:

Minoan

The Minoans!!! Ancient Civilization of Crete, Greece in 3D High Definition, 3:59

The Minoan civilization was an Aegean Bronze Age civilization that arose on the island of Crete and other Aegean islands and flourished from approximately 3650 to 1400 BC.[1] It was rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century through the work of British archaeologist Arthur Evans. Historian Will Durant referred to it as "the first link in the European chain."[2]

It was not until roughly 5000 BC in the late Neolithic period, that the first signs of advanced agriculture appeared in the Aegean, marking the first signs of civilization. The term "Minoan" refers to the mythic King Minos. Minos was associated in Greek myth with the labyrinth and the minotaur, which Evans identified with the site at Knossos, the largest Bronze Age Minoan site. The poet Homer recorded a tradition that Crete once had 90 cities.[3]

The Minoans were primarily a mercantile people engaged in overseas trade. Their pottery provides the best means of dating. As traders and artists, their cultural influence reached far beyond the island of Crete — throughout the Cyclades, to Egypt's Old Kingdom, to copper-bearing Cyprus, Canaan, and the Levantine coasts beyond, and to Anatolia. Some of its best art is preserved in the city of Akrotiri, on the island of Santorini, very near the Thera eruption.

Though we cannot read their language (Linear A), and there is much dispute, it is generally assumed there was little internal armed conflict in Minoan Crete itself, until the following Mycenaean period. The armed Mycenaeans or the eruption at Thera are two popular theories for the eventual demise of Minoan civilization around 1,400 BC.

https://youtu.be/P3Ez8drCIvc

There is recent stone tool evidence that humans – either prehuman hominins or early modern humans – reached the island of Crete perhaps as early as 130,000 years ago; however, the evidence for the first anatomically modern human presence dates to 10,000–12,000 years ago.[3][4] It was not until 5000 BCE in the Neolithic period that the first signs of advanced agriculture appeared in the Aegean, marking the beginning of civilization.

The "Palace" and Grave Circle A at Mycenae, c. 1600-1100 B.C.E., 4:12

Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris More free lessons at: http://www.khanacademy.org/video?v=S7...

https://youtu.be/S7HJB0PtiW0

Mycenaean Greece refers to the last phase of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece (c. 1600–1100 BCE). It represents the first advanced civilization in mainland Greece, with its palatial states, urban organization, works of art and writing system.[1]

Among the centers of power that emerged, the most notable were those of Pylos, Tiryns, Midea in the Peloponnese, Orchomenos, Thebes, Athens in Central Greece and Iolcos in Thessaly. The most prominent site was Mycenae, in Argolid, to which the culture of this era owes its name. Mycenaean and Mycenaean-influenced settlements also appeared in Epirus,[2][3] Macedonia,[4][5] on islands in the Aegean Sea, on the coast of Asia Minor, the Levant,[6] Cyprus[7] and Italy.[8]

Mycenaean Greece perished with the collapse of Bronze-Age culture in the eastern Mediterranean. Various theories have been proposed for the end of this civilization, among them the Dorian invasion or activities connected to the “Sea People”. Additional theories such as natural disasters and climatic changes have been also suggested. The Mycenaean period became the historical setting of much ancient Greek literature and mythology, including the Trojan Epic Cycle.[9]

Homer (Ancient Greek: Ὅμηρος [hómɛːros], Hómēros) is best known as the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey. He was believed by the ancient Greeks to have been the first and greatest of the epic poets. Author of the first known literature of Europe, he is central to the Western canon.

The science behind the myth: Homer's "Odyssey" - Matt Kaplan, 4:31

View full lesson: http://ed.ted.com/lessons/the-science... Homer's "Odyssey" recounts the adventures of the Greek hero Odysseus during his journey home from the Trojan War. Though some parts may be based on real events, the encounters with monsters, giants and magicians are considered to be complete fiction. But might there be more to these myths than meets the eye? Matt Kaplan explains why there might be more reality behind the "Odyssey" than many realize. Lesson by Matt Kaplan, animation by Mike Schell.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CVo225pUaSA

AN AUTHENTIC READING ORIGINAL GREEK WITH ORIGINAL TRANSLATION OF HOMER'S ILIAD LINES 1- 25, 2:48

ORIGINAL TRANSLATION A 1-25 Cherish the wrath in song. Goddess. Of Peleus' son Achilleus' destructiveness. The tens of thousands of Achaians whose pains were set into place. Many strong souled heroes, to Hades gone before there time. They then the spoils and tools of war beseech birds of prey of all kinds. This be Zeus' everlasting council. 5 Out, should we not then, with the first that set them apart in rivalry Atreides, also king of the high council of men, and Zeus-like Achilleus. Who shall we say of the Gods set common rivalry upon both warriors? Leto's and Zeus' son: Since then, ruling lameness through disease, upon the army he let loose this evil. Causing the tribes to perish. 10 It was pointless for Chryseus to prepare prayers for Atreide. While then coming quickly around the ships of the Achaians in a fury, he had also brought for his daughter the fixed ransom. With wreaths in hand as well as far-shooting Apollo's golden high sceptre. And releasing it always upon the Achaians. 15 The Atreides' then naturally were two. Commanders of the people. ‹‹Atreides and also you other Achaians with the well-wrought greaves. To you may the Gods grant, them who have bed-chambers on Olympus, complete destruction of Priam's city. Blessing your home-coming afterwards. The child of mine release friends. The ransom accept. 20 Regard with awe Zeus' son far-shooting Apollo.›› There the other Achaians of which all shouted out to accept in reverence the holy and pure ranson. But not Atreides Agamemnon who chose to delight in anger. Yet badly he discharged.

Holding the highest of word he spoke:

https://youtu.be/kSDO9FnWFWA

When he lived, as well as whether he lived at all, is unknown. Herodotus estimates that Homer lived no more than 400 years before his own time, which would place him at around 850 BCE or later.[1]

Pseudo-Herodotus estimates that he was born 622 years before Xerxes I placed a pontoon bridge over the Hellespont in 480 BCE, which would place him at 1102 BCE, 168 years after the fall of Troy in 1270 BCE. These two end points are 252 years apart, representative of the differences in dates given by the other sources.[2]

The importance of Homer to the ancient Greeks is described in Plato's Republic, which portrays him as the protos didaskalos, "first teacher", of the tragedians, the hegemon paideias, "leader of Greek culture", and the ten Hellada pepaideukon, "teacher of [all] Greece".[3]

Homer's works, which are about fifty percent speeches,[4] provided models in persuasive speaking and writing that were emulated throughout the ancient and medieval Greek worlds.[5]

Fragments of Homer account for nearly half of all identifiable Greek literary papyrus finds in Egypt.[6]

The Greeks of the sixth and early fifth centuries BCE understood by the works of "Homer", generally, "the whole body of heroic tradition as embodied in hexameter verse".[59]

The entire Epic Cycle was included.

The genre included further poems on the Trojan War, such as the Little Iliad, the Nostoi, the Cypria, and the Epigoni, as well as the Theban poems about Oedipus and his sons.

Other works, such as the corpus of Homeric Hymns, the comic mini-epic Batrachomyomachia ("The Frog-Mouse War"), and the Margites, were also attributed to him.

Two other poems, the Capture of Oechalia and the Phocais were also assigned Homeric authorship.

Epics

Herodotus mentions both the Iliad and the Odyssey as works of Homer.[60]He quotes a few lines from them both, which are the same in today’s editions.

The passage quoted from the Iliad mentions that Paris stopped at Sidon before bringing Helen to Troy.

From the fact that the Cypria has Paris going directly to Troy from Sparta, Herodotus concludes that it was not written by Homer. The doubting process had begun.

In Works and Days, Hesiod says that he crossed to Euboea to contend in the games held by the sons of Amphidamas at Chalcis.[61]

There he won with a hymnos and took away the prize of a tripod, which he dedicated to the Muses of Mount Helicon, where he first began with aoide, “song.”

One of the vitae, the “Certamen”, picks up this theme. Homer and Hesiod were contemporaries, it says.

They both attended the funeral games of Amphidamas, conducted by his son, Ganyctor, and both contended in the contest of sophia, “wit.”

In it, one was required to ask a question of the other, who must reply in verse.

Unable to decide, the judge had them each recite from their poems.

Hesiod quoted Works and Days; Homer, ‘Iliad’, both as they are now, but neither poem can have been the modern.

Hesiod cannot have described beforehand the very event in which he was participating.

The Iliad is supposed to have been written already.

It is not called that, however. The victory was given to Hesiod because his poem was about peace, but Homer’s, about war.

After the contest, Homer continued his wandering, composing and reciting epic poetry.

The “Certamen” mentions the Thebais, quoting the first line, which differs but little from the first line of the Iliad as it is now.

It had 7000 lines, as did the subsequent Epigoni, with a similar first line.

The “Certamen” qualifies the attribution to Homer with “some say ….” Subsequently he wrote the epitaph for Midas’ tomb, for which he got a silver bowl, and then the Odyssey in 12,000 lines (today’s is 12110).

He had already written the Iliad in 15,500 lines (today’s is 15693). Just these three epics alone are 34,500 lines, word-for-word, we are asked to believe, without reference to the rest of the prodigious Epic Cycle.

Then he went to Athens, and to Argos, where he delivered lines 559-568 of Book 2 of the Iliad with the addition of two more not in the current version.

Subsequently he went to Delos, where he delivered the Hymn to Apollo, and was made a citizen of all the Ionian states. Going finally to Ios he slipped on some clay and suffered a fatal fall.

The term “Epic Cycle” (Epikos Kuklos) refers to a series of ten epic poems written by different authors purporting to tell an interconnected sequence of stories covering all Greek mythology. Themes were selected from them for Greek drama as well. The name appears in the Chrestomathia of Eutychius Proclus, a synopsis of Greek literature, known only through further abridged fragments written by Photios I of Constantinople. No etymology was given. Evelyn-White hypothesizes that they were “written round” the Iliad and Odyssey and had a “clearly imitative” structure.[62] In this view Homer need have written no more than the Iliad, or the Iliad and Odyssey, with the Homeridae responsible for all the rest. The unity of theme and structure came from the close association of the authors in the guild or school.

Proclus does not subscribe to the authorships of the “Certamen”. He provides the names of other authors where they were available in his sources. These 10 epics, of which only Photius’ abridgements of Proclus’ synopses survive, and scattered fragments of other authors in other times, are as follows.

First and oldest, the “War of the Titans” (Titanomachia), eight fragments, is said to have been written by either Eumelus of Corinth, floruit 760-740 BCE, or Arctinus of Miletus, floruit in the First Olympiad, starting 776 BCE.[63]

The Theban Cycle consists of three epics:[64] “Story of Oedipus” (Oidipodeia), 6600 lines by Cinaethon of Sparta, floruit 764 BCE;[65] “Thebaid” (Thebais), attributed to Homer;[66] and “Epigoni (Epigonoi), attributed to Homer.[67] The Trojan Cycle consists of six epics and the Iliad and Odyssey, eight in all:[62] “Cyprian Lays” (kupria) in 11 books, attributed to either Homer, Stasinus, a younger contemporary of Homer, or one Hegesias;[68] “Aethiopis” (Aithiopis) in five books, sequent of the Iliad, which is a sequent of Cypria, by Arctinus;[69] “Little Iliad” (Ilias Mikra) in four books by Lesches of Mitylene, floruit 660 BCE;[70] “Sack of Ilium” (Iliou Persis) by Arctinus;[71] “Returns” (Nostoi) by Agias of Troezen,[72] floruit 740 BCE; and “Telegony” (Telegonia), by Eugammon of Cyrene, floruit 567 BCE.

The Greek Polis, 4:16

A basic documentary on the role of the Polis in ancient Greek society.

https://youtu.be/6r3kY4p5beY

The Ancient Greek city-state developed during the Archaic period as the ancestor of city, state, and citizenship and persisted (though with decreasing influence) well into Roman times, when the equivalent Latin word was civitas, also meaning "citizenhood", while municipium applied to a non-sovereign local entity.

The term "city-state", which originated in English (alongside the German Stadtstaat), does not fully translate the Greek term. The poleis were not like other primordial ancient city-states like Tyre or Sidon, which were ruled by a king or a small oligarchy, but rather political entities ruled by their bodies of citizens. The traditional view of archaeologists—that the appearance of urbanization at excavation sites could be read as a sufficient index for the development of a polis—was criticised by François Polignac in 1984[1][a] and has not been taken for granted in recent decades: the polis of Sparta, for example, was established in a network of villages. The term polis, which in archaic Greece meant "city", changed with the development of the governance center in the city to signify "state" (which included its surrounding villages). Finally, with the emergence of a notion of citizenship among landowners, it came to describe the entire body of citizens. The ancient Greeks did not always refer to Athens, Sparta, Thebes, and other poleis as such; they often spoke instead of the Athenians, Lacedaemonians, Thebans and so on. The body of citizens came to be the most important meaning of the term polis in ancient Greece.

The Greek term that specifically meant the totality of urban buildings and spaces is ἄστυ (pronounced [ásty]).

The polis in Ancient Greek philosophy

Plato analyzes the polis in The Republic, whose Greek title, Πολιτεία (Politeia), itself derives from the word polis. The best form of government of the polis for Plato is the one that leads to the common good. The philosopher king is the best ruler because, as a philosopher, he is acquainted with the Form of the Good. In Plato's analogy of the ship of state, the philosopher king steers the polis, as if it were a ship, in the best direction.Books II–IV of The Republic are concerned with Plato addressing the makeup of an ideal polis. In The Republic, Socrates is concerned with the two underlying principles of any society: mutual needs and differences in aptitude. Starting from these two principles, Socrates deals with the economic structure of an ideal polis. According to Plato, there are five main economic classes of any polis: producers, merchants, sailors/shipowners, retail traders, and wage earners. Along with the two principles and five economic classes, there are four virtues. The four virtues of a "just city" include, wisdom, courage, moderation, and justice. With all of these principles, classes, and virtues, it was believed that a "just city" (polis) would exist.

Archaic and classical poleis

The basic and indicating elements of a polis are:- Self-governance, autonomy, and independence (city-state)

- Agora: the social hub and financial marketplace, on and around a centrally located, large open space

- Acropolis: the citadel, inside which a temple had replaced the erstwhile Mycenaean anáktoron (palace) or mégaron (hall)

- Greek urban planning and architecture, public, religious, and private (see Hippodamian plan)

- Temples, altars, and sacred precincts: one or more are dedicated to the poliouchos, the patron deity of the city; each polis kept its own particular festivals and customs (Political religion, as opposed to the individualized religion of later antiquity). Priests and priestesses, although often drawn from certain families by tradition, did not form a separate collegiality or class; they were ordinary citizens who on certain occasions were called to perform certain functions.

- Gymnasia

- Theatres

- Walls: used for protection from invaders

- Coins: minted by the city, and bearing its symbols

- Colonies being founded by the oikistes of the metropolis

- Political life: it revolved around the sovereign Ekklesia (the assembly of all adult male citizens for deliberation and voting), the standing boule and other civic or judicial councils, the archons and other officials or magistrates elected either by vote or by lot, clubs, etc., and sometimes punctuated by stasis (civil strife between parties, factions or socioeconomic classes, e.g., aristocrats, oligarchs, democrats, tyrants, the wealthy, the poor, large, or small landowners, etc.). They practised direct democracy.

- Publication of state functions: laws, decrees, and major fiscal accounts were published, and criminal and civil trials were also held in public.

- Synoecism, conurbation: Absorption of nearby villages and countryside, and the incorporation of their tribes into the substructure of the polis. Many of a polis' citizens lived in the suburbs or countryside. The Greeks regarded the polis less as a territorial grouping than as a religious and political association: while the polis would control territory and colonies beyond the city itself, the polis would not simply consist of a geographical area. Most cities were composed of several tribes or phylai, which were in turn composed of phratries (common-ancestry lineages), and finally génea (extended families).

- Social classes and citizenship: Dwellers of the polis were generally divided into four types of inhabitants, with status typically determined by birth:

- Citizens with full legal and political rights—that is, free adult men born legitimately of citizen parents. They had the right to vote, be elected into office, and bear arms, and the obligation to serve when at war.

- Citizens without formal political rights but with full legal rights: the citizens' female relatives and underage children, whose political rights and interests were meant to be represented by their adult male relatives.

- Citizens of other poleis who chose to reside elsewhere (the metics, μέτοικοι, métoikoi, literally "transdwellers"): though free-born and possessing full rights in their place of origin, they had full legal rights but no political rights in their place of residence. Metics could not vote, be elected to office, bear arms, or serve in war. They otherwise had full personal and property rights, albeit subject to taxation.

- Slaves: chattel in full possession of their owner, and with no privileges other than those that their owner would grant (or revoke) at will.

New York Kouros, c. 590–580 B.C.E., 5:52

Marble Statue of a Kouros (New York Kouros), c. 590–580 B.C.E. (Attic, archaic), Naxian marble, 194.6 x 51.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) More free lessons at: http://www.khanacademy.org/video?v=Ax...

https://youtu.be/Ax8vcxRtmHY

In Ancient Greek kouros means "youth, boy, especially of noble rank." The term kouros, was first proposed for what were previously thought to be depictions of Apollo by V. I. Leonardos in 1895 in relation to the youth from Keratea,[2] and adopted by Henri Lechat as a generic term for the standing male figure in 1904.[3] Such statues are found across the Greek-speaking world, the preponderance of these were found in sanctuaries of Apollo with more than one hundred from the sanctuary of Apollo Ptoios, Boeotia, alone.[4] These free-standing sculptures were typically marble, but also the form is rendered in limestone, wood, bronze, ivory and terracotta. They are typically life-sized, though early colossal examples are up to 3 meters tall.

The female sculptural counterpart of the kouros is the kore.

Who or what inspired the rise of democracy in Athens?

Focusing on the interaction of Homeric epic and the visual arts, this is the second of five modules on the Ancient Greek Hero as portrayed in classical literature, song, performance, art, and cult.

Register for The Ancient Greek Hero (Hours 6-11) from Harvard University at https://www.edx.org/course/harvardx/h...

About this Course

HUM 2.2x. The second of five modules in The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours, “Hours 6-11: Signs of the Hero in Epic and Iconography” explores the interactions of text and image in a culture where the “text” is not a written document but a live performance and where the “image” is not based on anything that is written down but exists as a free-standing medium of the visual arts, expressing the same myths that are being systematically expressed by the medium of Homeric poetry. Almost all of the images we will be studying are samples of a form of vase painting known as the “Black Figure” technique. We will practice how to “read” such a medium, analyzing what it tells us about ancient Greek heroes like Achilles, in conjunction with our “reading” the performance tradition of the Homeric Iliad itself.

It is important to keep in mind, as we read these images and texts together, that the myths expressed by these media were meant to be taken very seriously. In the ancient Greek song culture, myth was not mere fiction. Just the opposite: myth was a formulation of eternal cosmic truths! So, the myths conveyed by the images of the paintings we will study are just as “truthful,” from the standpoint of ancient Greek song culture, as are the related myths conveyed by the Homeric Iliad. We need to read both the texts and the images of these myths as an accurate formulation of an integral system of thought the expresses most clearly and authoritatively all those things that really matter in life.

Additionally, this module foregrounds the historical fact, explored more fully in the third module (“Hours 12-15: The Cult of Heroes”), that the heroes who were characters in the myths of ancient Greek epic, lyric, and other verbal media were at the same time worshipped as superhuman forces by the communities where their bodies were thought to be hidden from outsiders. When we take for example the Homeric Odyssey, we find that the main hero of this epic, Odysseus, was a cult hero, not only an epic hero. And the agenda that center on the idea of a cult hero, like the prospect of immortalization after death, can be clearly seen in the overall plot of the Odyssey, especially in the memorable scene where the hero experiences his homecoming to Ithaca at the same moment when the sun rises as he wakes from a mystical overnight sleep while sailing homeward.

See other courses in this series:

Module 1, “Hours 1-5: Epic and Lyric”

Module 3, “Hours 12-15: Cult of Heroes”

Module 4, “Hours 16-21: The Hero in Tragedy”

Module 5, “Hours 22-24: Plato and Beyond”

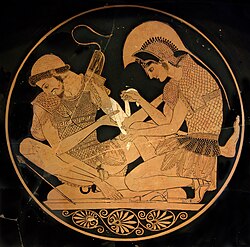

Achilles tending the wounded Patroclus

(Attic red-figure kylix, c. 500 BC)

Although the story covers only a few weeks in the final year of the war, the Iliad mentions or alludes to many of the Greek legends about the siege; the earlier events, such as the gathering of warriors for the siege, the cause of the war, and related concerns tend to appear near the beginning.

Then the epic narrative takes up events prophesied for the future, such as Achilles' looming death and the sack of Troy, prefigured and alluded to more and more vividly, so that when it reaches an end, the poem has told a more or less complete tale of the Trojan War.

The Iliad is paired with something of a sequel, the Odyssey, also attributed to Homer. Along with the Odyssey, the Iliad is among the oldest extant works of Western literature, and its written version is usually dated to around the eighth century BC.[2] Recent statistical modelling based on language evolution gives a date of 760–710 BC.[3] In the modern vulgate (the standard accepted version), the Iliad contains 15,693 lines; it is written in Homeric Greek, a literary amalgam of Ionic Greek and other dialects.

Greek text of the Odyssey's opening passage

The Odyssey (/ˈɒdəsi/;[1] Greek: Ὀδύσσεια Odýsseia, pronounced [o.dýs.sej.ja] in Classical Attic) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer.

It is, in part, a sequel to the Iliad, the other work ascribed to Homer. The poem is fundamental to the modern Western canon, and is the second oldest extant work of Western literature, the Iliad being the oldest. Scholars believe it was composed near the end of the 8th century BC, somewhere in Ionia, the Greek coastal region of Anatolia.[2]

The poem mainly focuses on the Greek hero Odysseus (known as Ulysses in Roman myths) and his journey home after the fall of Troy. It takes Odysseus ten years to reach Ithaca after the ten-year Trojan War.[3] In his absence, it is assumed he has died, and his wife Penelope and son Telemachus must deal with a group of unruly suitors, the Mnesteres (Greek: Μνηστῆρες) or Proci, who compete for Penelope's hand in marriage.

It continues to be read in the Homeric Greek and translated into modern languages around the world. Many scholars believe that the original poem was composed in an oral tradition by an aoidos (epic poet/singer), perhaps a rhapsode (professional performer), and was more likely intended to be heard than read.[2]

The details of the ancient oral performance, and the story's conversion to a written work inspire continual debate among scholars. The Odyssey was written in a poetic dialect of Greek—a literary amalgam of Aeolic Greek, Ionic Greek, and other Ancient Greek dialects—and comprises 12,110 lines of dactylic hexameter.[4][5] Among the most noteworthy elements of the text are its non-linear plot, and the influence on events of choices made by women and serfs, besides the actions of fighting men. In the English language as well as many others, the word odyssey has come to refer to an epic voyage.

The Odyssey has a lost sequel, the Telegony, which was not written by Homer. It was usually attributed in antiquity to Cinaethon of Sparta. In one source, the Telegony was said to have been stolen from Musaeus by Eugamon or Eugammon of Cyrene (see Cyclic poets).

From the film, 300

300 is a 2007 American epic fantasy war film based on the 1998 comic series of the same name by Frank Miller and Lynn Varley. Both are fictionalized retellings of the Battle of Thermopylae within the Persian Wars. The film was directed by Zack Snyder, while Miller served as executive producer and consultant. It was filmed mostly with a super-imposition chroma key technique, to help replicate the imagery of the original comic book.

The plot revolves around King Leonidas (Gerard Butler), who leads 300 Spartans into battle against the Persian "god-King" Xerxes (Rodrigo Santoro) and his invading army of more than 300,000 soldiers.

As the battle rages, Queen Gorgo (Lena Headey) attempts to rally support in Sparta for her husband. The story is framed by a voice-over narrative by the Spartan soldier Dilios (David Wenham). Through this narrative technique, various fantastical creatures are introduced, placing 300 within the genre of historical fantasy.

300 was released in both conventional and IMAX theaters in the United States on March 9, 2007, and on DVD, Blu-ray Disc, and HD DVD on July 31, 2007. The film received mixed reviews, receiving acclaim for its original visuals and style, but criticism for favoring visuals over characterization and its depiction of the ancient Persians in Iran, a characterization which some had deemed racist; however, the film was a box office success, grossing over $450 million, with the film's opening being the 24th largest in box office history at the time. A sequel, 300: Rise of an Empire, which is based on Miller's unpublished graphic novel prequel Xerxes, was released on March 7, 2014.

https://youtu.be/QkWS9PiXekE

The Sacred Sanctuaries

The sacred geography of Ancient Greece.

The ancient Greek wised men claimed that the ancient Greek sanctuaries and cities were not founded in random places, but there was a mathematical and geometrical link between them. This claim meant to be proved nowadays by the use of modern resources. The equal distances between cities and sanctuaries that continually are being discovered, is the evidence that ancient Greece is a vast geometric world. The huge question is how the ancient Greek succeeded to use perfectly such a technology without the modern tools we have today? Which is the lost knowledge that it hasn' t been reached nowadays? A big thanks to my dear friend Kassandreia for the translation in English Music song : Jean Michel Jarre - Oxygene 2

https://youtu.be/fS4MeCZJ4XI

Olympia and the Olympic Games

View full lesson:

http://ed.ted.com/lessons/the-ancient-origins-of-the-olympics-armand-d-angour#review

Thousands of years in the making, the Olympics began as part of a religious festival honoring the Greek god Zeus in the rural Greek town of Olympia.

But how did it become the greatest show of sporting excellence on earth? Armand D’Angour explains the evolution of the Olympics.

Lesson by Armand D'Angour, animation by Diogo Viegas.

https://youtu.be/VdHHus8IgYA

Male Sculpture and the Cult of the Body

https://youtu.be/Q5IWDhXtsmE

Egyptian Influences

https://youtu.be/4JWGBMAgjqs

Time Travelling for Democracy: Athenian Democracy vs. American Democracy, 5:29

A man and woman are working in a government laboratory when the man discovers that a fellow scientist has perished during time travel. The female scientist offers to go in his place for the purpose of warning the Athenians of their doomed democracy. When she arrives in Ancient Athens, she meets an Athenian man whom she attempts to warn. Meanwhile, they discuss the differences between American and Athenian democracies before the female scientist heads back to the future, only to meet her own doom.

https://youtu.be/7hsJQTndbCM

Female Sculpture and the Worship of Athena

Classical studies professor John Oakley previews the upcoming Athenian Potters and Painters conference as well as the complementary exhibition at the Muscarelle Museum of Art.

https://youtu.be/hcUkpc81164

The Poetry of Sappho

https://youtu.be/zQPLDqPdrN4

Consider these two great epics of heroes and choices, along with their virtues and flaws. Dip into these bedrock stories of the western tradition.

Iliad and the Odyssey

https://blackboard.strayer.edu/bbcswebdav/institution/HUM/111/1146/Week3/WYLTKM-IliadOdyssey/story.html

Why Greece Matters- Victor Davis Hanson, 41:39

Why Greece Matters is a lecture on the positive influence ancient Greece has had on the development and formation of the West.

http://youtu.be/r-pOwv6ZIbM

Early Civilizations in Greece, 2:20

To meet the overall objectives we will cover the following topics in Part 1:

Minoan culture

The Minoan civilization flourished on the island of Crete from 2700 B.C. to 1450 B.C. Most historians believe it was destroyed by the Mycenaeans from the Greek mainland. The Mycenaean civilization consisted of powerful monarchies that flourished between 1600 B.C. and 1100 B.C. After the collapse of this civilization, Greece entered a period known as the Dark Age. Food production decreased, and the population declined. At the same time, Greeks sailed extensively on the Aegean Sea and settled on islands and in Asia Minor. Iron replaced bronze in the making of tools and weapons. During the eighth century, the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet, and Homer wrote his famous epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, chronicling the Trojan War.

Timeline of Minoan, Greek, and Roman Art

Cf. http://prezi.com/ma0ewu-xq47a/?utm_campaign=share&utm_medium=copy

- Mycenaean culture

Compare and Contrast

Use the diagram to help you study for the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations.

Lecture on Earlier Greece

- The Cyclades

- Minoan Culture in Crete

- Mycenaean Culture on the Mainland

- The Homeric Epics

https://youtu.be/XMlhD97Zwag

- The Rise of the Greek City-States

- Rise of the Greek City-States

- http://gmicksmithsocialstudies.blogspot.com/2012/07/world-history-i-chapter-4-ancient_6675.html

- The Sacred Sanctuaries

- The Athens of Peisistratus

- The FIrst Athenian Democracy

Lecture on Athens and the Hellenistic World

- The Good Life and the Politics of Athens

- Rebuilding the Acropolis

- Philosophy and the Polis

- The Theater of the People

- Theater of Ancient Greece

- http://prezi.com/pp2yhpcyxwnv/?utm_campaign=share&utm_medium=copy&rc=ex0share

- The Hellenistic World

Alexander and the Hellenistic Era

http://gmicksmithsocialstudies.blogspot.com/2012/07/world-history-i-chapter-4-ancient_5032.html

Question 1: Multiple Choice

-

Why did the Neolithic era witness increased pottery creation?

Why did the Neolithic era witness increased pottery creation?Given Answer:  Fragile pottery was impractical for Paleolithic hunter-gatherers.

Fragile pottery was impractical for Paleolithic hunter-gatherers.Correct Answer:  Fragile pottery was impractical for Paleolithic hunter-gatherers.

Fragile pottery was impractical for Paleolithic hunter-gatherers.

Question 2: Multiple Choice

-

The Ise shrine is razed and then rebuilt every 20 years to

The Ise shrine is razed and then rebuilt every 20 years toGiven Answer:  ritually celebrate renewal.

ritually celebrate renewal.Correct Answer:  ritually celebrate renewal.

ritually celebrate renewal.

Question 3: Multiple Choice

-

According to the most recent discoveries, Stonehenge was constructed as a

According to the most recent discoveries, Stonehenge was constructed as aGiven Answer:  burial ground.

burial ground.Correct Answer:  burial ground.

burial ground.

Question 4: Multiple Choice

-

In the Zuni emergence tale, the Pueblo people originated in

In the Zuni emergence tale, the Pueblo people originated inGiven Answer:  the womb of Mother Earth.

the womb of Mother Earth.Correct Answer:  the womb of Mother Earth.

the womb of Mother Earth.

Question 5: Multiple Choice

-

Japanese emperors claimed divinity as

Japanese emperors claimed divinity asGiven Answer:  direct descendants of the sun goddess.

direct descendants of the sun goddess.Correct Answer:  direct descendants of the sun goddess.

direct descendants of the sun goddess.

Question 6: Multiple Choice

-

Why is the Epic of Gilgamesh a first in known literary works?

Why is the Epic of Gilgamesh a first in known literary works?Given Answer:  It is the first to confront the idea of death

It is the first to confront the idea of deathCorrect Answer:  It is the first to confront the idea of death

It is the first to confront the idea of death

Question 7: Multiple Choice

-

What classic struggle do Gilgamesh and Enkidu represent?

What classic struggle do Gilgamesh and Enkidu represent?Given Answer:  Nature versus civilization

Nature versus civilizationCorrect Answer:  Nature versus civilization

Nature versus civilization

Question 8: Multiple Choice

-

What were ziggurats most likely designed to resemble?

What were ziggurats most likely designed to resemble?Given Answer:  A mountain

A mountainCorrect Answer:  A mountain

A mountain

Question 9: Multiple Choice

-

Which of the following differentiates the Hebrews from other Near Eastern cultures?

Which of the following differentiates the Hebrews from other Near Eastern cultures?Given Answer:  They worshipped a single god

They worshipped a single godCorrect Answer:  They worshipped a single god

They worshipped a single god

Question 10: Multiple Choice

As noted in the chapter's "Continuity and Change' section, what most distinguishes Mesopotamia from Egypt?

|

|||||

| |||||

3 The Stability of Ancient Egypt FLOOD AND SUN 67

The Nile and Its Culture 68

Egyptian Religion: Cyclical Harmony 70

Pictorial Formulas in Egyptian Art 71

The Old Kingdom 74

The Stepped Pyramid at Saqqara 74

Three Pyramids at Giza 75

Monumental Royal Sculpture: Perfection and Eternity 78

The Sculpture of the Everyday 79

The Middle Kingdom at Thebes 81

Middle Kingdom Literature 81

Middle Kingdom Sculpture 81

The New Kingdom 83

Temple and Tomb Architecture and Their Rituals 83

Akhenaten and the Politics of Religion 87

The Return to Thebes and to Tradition 89

The Late Period, the Kushites, and the Fall of Egypt 91

The Kushites 92

Egypt Loses Its Independence 92

READINGS

3.1 from Memphis, “This It Is Said of Ptah” (ca. 2300 bce) 71

3.2 The Teachings of Khety (ca. 2040–1648 bce) 95

3.3 from Akhenaten’s Hymn to the Sun (14th century bce) 88

3.4 from a Book of Going Forth by Day 90

FEATURES

CONTEXT

Major Periods of Ancient Egyptian History 70

Some of the Principal Egyptian Gods 71

The Rosetta Stone 77

CLOSER LOOK Reading the Palette of Narmer 72

MATERIALS & TECHNIQUES Mummification 86

CONTINUITY & CHANGE Mutual Influence through Trade 93

4 The Aegean World and the Rise of Greece TRADE, WAR, AND VICTORY 97

The Cultures of the Aegean 97

The Cyclades 98

Minoan Culture in Crete 99

Mycenaean Culture on the Mainland 102

The Homeric Epics 105

The Iliad 107

The Odyssey 108

The Greek Polis 110

Behavior of the Gods 112

The Competing Poleis 113

The Sacred Sanctuaries 114

Male Sculpture and the Cult of the Body 118

Female Sculpture and the Worship of Athena 120

Athenian Pottery 121

The Poetry of Sappho 123

The Rise of Athenian Democracy 124

Toward Democracy: Solon and Pisistratus 124

Cleisthenes and the First Athenian Democracy 125

READINGS

4.1 from Homer, Iliad, Book 16 (ca. 750 bce) 128

4.1a from Homer, Iliad, Book 24 (ca. 750 bce) 108

4.2 from Homer, Odyssey, Book 9 (ca 725 bce) 130

4.2a from Homer, Odyssey, Book 4 (ca. 725 bce) 108

4.2b from Homer, Odyssey, Book 1 (ca. 725 bce) 109

4.3 from Hesiod, Works and Days (ca. 700 bce) 112

4.4 from Hesiod, Theogony (ca. 700 bce) 112

4.5 Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian Wars 113

4.6a–b Sappho, lyric poetry 124

4.7 from Aristotle’s Athenian Constitution 125

FEATURES

CONTEXT The Greek Gods 114

CLOSER LOOK The Classical Orders 116

CONTINUITY & CHANGE Egyptian and Greek Sculpture 126

Question 1: Multiple Choice

-

Why did the Egyptian sculptors idealize rulers in their sculptures?

Why did the Egyptian sculptors idealize rulers in their sculptures?Given Answer:  The rulers' perfection mirrored the perfection of the gods themselves

The rulers' perfection mirrored the perfection of the gods themselvesCorrect Answer:  The rulers' perfection mirrored the perfection of the gods themselves

The rulers' perfection mirrored the perfection of the gods themselves

Question 2: Multiple Choice

-

Why are archaeologists so certain that Egypt had contact with other civilizations?

Why are archaeologists so certain that Egypt had contact with other civilizations?Given Answer:  Egyptian artifacts have been discovered throughout the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Mesopotamian worlds

Egyptian artifacts have been discovered throughout the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Mesopotamian worldsCorrect Answer:  Egyptian artifacts have been discovered throughout the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Mesopotamian worlds

Egyptian artifacts have been discovered throughout the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Mesopotamian worlds

Question 3: Multiple Choice

-

Which god did the Egyptians believe the king personified?

Which god did the Egyptians believe the king personified?Given Answer:  Horus

HorusCorrect Answer:  Horus

Horus

Question 4: Multiple Choice

-

Why is Nebamun Hunting Birds a sort of visual pun?

Why is Nebamun Hunting Birds a sort of visual pun?Given Answer:  The artist depicts actions that reflect sexual procreation, not hunting

The artist depicts actions that reflect sexual procreation, not huntingCorrect Answer:  The artist depicts actions that reflect sexual procreation, not hunting

The artist depicts actions that reflect sexual procreation, not hunting

Question 5: Multiple Choice

-

The Egyptian word for sculpture is the same as the word for what other act?

The Egyptian word for sculpture is the same as the word for what other act?Given Answer:  Giving birth

Giving birthCorrect Answer:  Giving birth

Giving birth

Question 6: Multiple Choice

-

Why is the palace at Knossos known as the House of the Double Axes?

Why is the palace at Knossos known as the House of the Double Axes?Given Answer:  Representations of double axes decorated it

Representations of double axes decorated itCorrect Answer:  Representations of double axes decorated it

Representations of double axes decorated it

Question 7: Multiple Choice

-

What are the three orders of classical Greek architecture?

What are the three orders of classical Greek architecture?Given Answer:  Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian

Doric, Ionic, and CorinthianCorrect Answer:  Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian

Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian

Question 8: Multiple Choice

-

What is the Greek concept of arête?

What is the Greek concept of arête?Given Answer:  Being the best one can be

Being the best one can beCorrect Answer:  Being the best one can be

Being the best one can be

Question 9: Multiple Choice

-

The term ceramics comes from which of the following?

The term ceramics comes from which of the following?Given Answer:  Kerameikos, a cemetery in Athens

Kerameikos, a cemetery in AthensCorrect Answer:  Kerameikos, a cemetery in Athens

Kerameikos, a cemetery in Athens

Question 10: Multiple Choice

How do Minoan frescoes differ from Egyptian frescoes?

|

|||||

| |||||

Question 1: Multiple Choice

-

Why were Egyptians buried with Books of Going Forth by Day (Books of the Dead)?

Why were Egyptians buried with Books of Going Forth by Day (Books of the Dead)?Given Answer:  To help them survive the ritual of judgment

To help them survive the ritual of judgmentCorrect Answer:  To help them survive the ritual of judgment

To help them survive the ritual of judgment

Question 2: Multiple Choice

-

Why did Egyptian artists paint human's faces, arms, legs, and feet in profile?

Why did Egyptian artists paint human's faces, arms, legs, and feet in profile?Given Answer:  They believed it was the most characteristic view

They believed it was the most characteristic viewCorrect Answer:  They believed it was the most characteristic view

They believed it was the most characteristic view

Question 3: Multiple Choice

-

The Egyptian word for sculpture is the same as the word for what other act?

The Egyptian word for sculpture is the same as the word for what other act?Given Answer:  Giving birth

Giving birthCorrect Answer:  Giving birth

Giving birth

Question 4: Multiple Choice

-

Why did the Egyptians bury their dead on the west side of the Nile?

Why did the Egyptians bury their dead on the west side of the Nile?Given Answer:  Because of the symbolic reference to death and rebirth, as the sun sets in the west

Because of the symbolic reference to death and rebirth, as the sun sets in the westCorrect Answer:  Because of the symbolic reference to death and rebirth, as the sun sets in the west

Because of the symbolic reference to death and rebirth, as the sun sets in the west

Question 5: Multiple Choice

-

Why can the reliefs on Ramses II's pylon gate at Luxor be viewed as propaganda rather than historical?

Why can the reliefs on Ramses II's pylon gate at Luxor be viewed as propaganda rather than historical?Given Answer:  The battle scene they describe was not the major success depicted

The battle scene they describe was not the major success depictedCorrect Answer:  The battle scene they describe was not the major success depicted

The battle scene they describe was not the major success depicted

Question 6: Multiple Choice

-

How do Minoan frescoes differ from Egyptian frescoes?

How do Minoan frescoes differ from Egyptian frescoes?Given Answer:  Minoan frescoes were painted with oil, not water-based, pigment

Minoan frescoes were painted with oil, not water-based, pigmentCorrect Answer:  Minoan frescoes appear on walls of homes and palaces, not tombs

Minoan frescoes appear on walls of homes and palaces, not tombs

Question 7: Multiple Choice

-

What new architectural form did the Mycenaeans develop to bury their kings?

What new architectural form did the Mycenaeans develop to bury their kings?Given Answer:  Tholos

TholosCorrect Answer:  Tholos

Tholos

Question 8: Multiple Choice

-

As discussed in the chapter's "Continuity and Change," which of the following cultures seems to have had the greatest influence on Archaic Greek sculpture?

As discussed in the chapter's "Continuity and Change," which of the following cultures seems to have had the greatest influence on Archaic Greek sculpture?Given Answer:  Cycladic

CycladicCorrect Answer:  Egyptian

Egyptian

Question 9: Multiple Choice

-

What is the Greek concept of arête?

What is the Greek concept of arête?Given Answer:  Being the best one can be

Being the best one can beCorrect Answer:  Being the best one can be

Being the best one can be

Question 10: Multiple Choice

Why are the more than 100 Aegean islands between mainland Greece and Crete known as the Cyclades?

|

|||||

| |||||

Question 1: Multiple Choice

-

Why were Egyptians buried with Books of Going Forth by Day (Books of the Dead)?

Why were Egyptians buried with Books of Going Forth by Day (Books of the Dead)?Given Answer:  To provide instructions for resurrection

To provide instructions for resurrectionCorrect Answer:  To help them survive the ritual of judgment

To help them survive the ritual of judgment

Question 2: Multiple Choice

-

Why did the Egyptians believe that a good deity like Osiris required a bad deity like Seth?

Why did the Egyptians believe that a good deity like Osiris required a bad deity like Seth?Given Answer:  Opposites were necessary for balance, harmony, and cycles

Opposites were necessary for balance, harmony, and cyclesCorrect Answer:  Opposites were necessary for balance, harmony, and cycles

Opposites were necessary for balance, harmony, and cycles

Question 3: Multiple Choice

-

What is one of the greatest changes that took place during the Middle Kingdom?

What is one of the greatest changes that took place during the Middle Kingdom?Given Answer:  Writing and literature moved from the sacred to the imaginative

Writing and literature moved from the sacred to the imaginativeCorrect Answer:  Writing and literature moved from the sacred to the imaginative

Writing and literature moved from the sacred to the imaginative

Question 4: Multiple Choice

-

Why are archaeologists so certain that Egypt had contact with other civilizations?

Why are archaeologists so certain that Egypt had contact with other civilizations?Given Answer:  Egyptian artifacts have been discovered throughout the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Mesopotamian worlds

Egyptian artifacts have been discovered throughout the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Mesopotamian worldsCorrect Answer:  Egyptian artifacts have been discovered throughout the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Mesopotamian worlds

Egyptian artifacts have been discovered throughout the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Mesopotamian worlds

Question 5: Multiple Choice

-

Why was deciphering the Rosetta Stone so significant?

Why was deciphering the Rosetta Stone so significant?Given Answer:  The Stone provided the key to reading hieroglyphs

The Stone provided the key to reading hieroglyphsCorrect Answer:  The Stone provided the key to reading hieroglyphs

The Stone provided the key to reading hieroglyphs

Question 6: Multiple Choice

-

The term ceramics comes from which of the following?

The term ceramics comes from which of the following?Given Answer:  Kerameikos, a cemetery in Athens

Kerameikos, a cemetery in AthensCorrect Answer:  Kerameikos, a cemetery in Athens

Kerameikos, a cemetery in Athens

Question 7: Multiple Choice

-

Why are the more than 100 Aegean islands between mainland Greece and Crete known as the Cyclades?

Why are the more than 100 Aegean islands between mainland Greece and Crete known as the Cyclades?Given Answer:  The islands form a rough circular shape

The islands form a rough circular shapeCorrect Answer:  The islands form a rough circular shape

The islands form a rough circular shape

Question 8: Multiple Choice

-

Why is the palace at Knossos known as the House of the Double Axes?

Why is the palace at Knossos known as the House of the Double Axes?Given Answer:  Representations of double axes decorated it

Representations of double axes decorated itCorrect Answer:  Representations of double axes decorated it

Representations of double axes decorated it

Question 9: Multiple Choice

-

How do Minoan frescoes differ from Egyptian frescoes?

How do Minoan frescoes differ from Egyptian frescoes?Given Answer:  Minoan frescoes appear on walls of homes and palaces, not tombs

Minoan frescoes appear on walls of homes and palaces, not tombsCorrect Answer:  Minoan frescoes appear on walls of homes and palaces, not tombs

Minoan frescoes appear on walls of homes and palaces, not tombs

Question 10: Multiple Choice

What are the three orders of classical Greek architecture?

|

|||||

| |||||

Question 1: Multiple Choice

-

The Egyptian word for sculpture is the same as the word for what other act?

The Egyptian word for sculpture is the same as the word for what other act?Given Answer:  Giving birth

Giving birthCorrect Answer:  Giving birth

Giving birth

Question 2: Multiple Choice

-

Why did the Egyptians believe that a good deity like Osiris required a bad deity like Seth?

Why did the Egyptians believe that a good deity like Osiris required a bad deity like Seth?Given Answer:  Opposites were necessary for balance, harmony, and cycles

Opposites were necessary for balance, harmony, and cyclesCorrect Answer:  Opposites were necessary for balance, harmony, and cycles

Opposites were necessary for balance, harmony, and cycles

Question 3: Multiple Choice

-

What creature, part crocodile, part lion, and part hippopotamus, would devour the unworthy deceased at the final judgment?

What creature, part crocodile, part lion, and part hippopotamus, would devour the unworthy deceased at the final judgment?Given Answer:  Ammit

AmmitCorrect Answer:  Ammit

Ammit

Question 4: Multiple Choice

-

Why was the Palette of Narmer created?

Why was the Palette of Narmer created?Given Answer:  For a votive gift to a god or goddess

For a votive gift to a god or goddessCorrect Answer:  For a votive gift to a god or goddess

For a votive gift to a god or goddess

Question 5: Multiple Choice

-

Why is Nebamun Hunting Birds a sort of visual pun?

Why is Nebamun Hunting Birds a sort of visual pun?Given Answer:  The artist depicts actions that reflect sexual procreation, not hunting

The artist depicts actions that reflect sexual procreation, not huntingCorrect Answer:  The artist depicts actions that reflect sexual procreation, not hunting

The artist depicts actions that reflect sexual procreation, not hunting

Question 6: Multiple Choice

-

What are the three orders of classical Greek architecture?

What are the three orders of classical Greek architecture?Given Answer:  Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian

Doric, Ionic, and CorinthianCorrect Answer:  Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian

Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian

Question 7: Multiple Choice

-

Why do we think the Cycladic figurines served a mortuary function?

Why do we think the Cycladic figurines served a mortuary function?Given Answer:  Most were found in graves

Most were found in gravesCorrect Answer:  Most were found in graves

Most were found in graves

Question 8: Multiple Choice

-

Why is the palace at Knossos known as the House of the Double Axes?

Why is the palace at Knossos known as the House of the Double Axes?Given Answer:  Representations of double axes decorated it

Representations of double axes decorated itCorrect Answer:  Representations of double axes decorated it

Representations of double axes decorated it

Question 9: Multiple Choice

-

The term ceramics comes from which of the following?

The term ceramics comes from which of the following?Given Answer:  Kerameikos, a cemetery in Athens

Kerameikos, a cemetery in AthensCorrect Answer:  Kerameikos, a cemetery in Athens

Kerameikos, a cemetery in Athens

Question 10: Multiple Choice

What is the Greek concept of arête?

|

|||||

| |||||

Question 1: Multiple Choice Correct Why in part did Sparta form its own Peloponnesian League? Given Answer: Correct Athens' use of Delian Fund leagues to rebuild its acropolis Correct Answer: Athens' use of Delian Fund leagues to rebuild its acropolis out of 3 points Question 2: Multiple Choice Correct What qualities define Hellenistic art? Given Answer: Correct Animation, drama, and psychological complexity Correct Answer: Animation, drama, and psychological complexity out of 3 points Question 3: Multiple Choice Correct Why does Sophocles' Antigone oppose her uncle, Creon? Given Answer: Correct She believes that burying her brother is her democratic right Correct Answer: She believes that burying her brother is her democratic right out of 3 points Question 4: Multiple Choice Correct Why did fifth-century Greeks not see themselves as at the mercy of the gods? Given Answer: Correct They believed natural forces were knowable, not punishment from a god Correct Answer: They believed natural forces were knowable, not punishment from a god out of 3 points Question 5: Multiple Choice Correct With which cult was drama originally associated? Given Answer: Correct The cult of Dionysus Correct Answer: The cult of Dionysus out of 3 points Question 6: Multiple Choice Correct Why did Augustus permanently banish the poet Ovid from Rome? Given Answer: Correct For indiscretion and writing Ars Amatoria, a guidebook for having affairs Correct Answer: For indiscretion and writing Ars Amatoria, a guidebook for having affairs out of 3 points Question 7: Multiple Choice Correct What is the symbolic heart of a Roman domus? Given Answer: Correct The atrium Correct Answer: The atrium out of 3 points Question 8: Multiple Choice Correct Why was the Arch of Titus constructed? Given Answer: Correct To celebrate Titus's sack of the Second Temple of Jerusalem Correct Answer: To celebrate Titus's sack of the Second Temple of Jerusalem out of 3 points Question 9: Multiple Choice Correct Why, by the end of the third century, were the Romans justified in feeling politically and culturally threatened by the Christians? Given Answer: Correct Christians made up nearly one-tenth of the empire's population Correct Answer: Christians made up nearly one-tenth of the empire's population out of 3 points Question 10: Multiple Choice Correct Why was the Pantheon constructed with a 30-foot-diameter oculus (hole) in its roof? Given Answer: Correct To symbolize Jupiter's ever-watchful eye over Rome Correct Answer: To symbolize Jupiter's ever-watchful eye over Rome