We will have two ten-minute breaks: at 7:30 - 7:40; and, at 9:00 pm - 9:10 pm. I will take roll after the second break before you are dismissed at 10 pm.

Facing the Divine: Exploring African masks as art connecting humans to the realm of spirits.

Pre-Built Course Content

Gothic architecture is a style of architecture that flourished during the high and late medieval period. It evolved from Romanesque architecture and was succeeded by Renaissance architecture. Originating in 12th-century France and lasting into the 16th century, Gothic architecture was known during the period as Opus Francigenum ("French work") with the term Gothic first appearing during the later part of the Renaissance. Its characteristics include the pointed arch, the ribbed vault and the flying buttress. Gothic architecture is most familiar as the architecture of many of the great cathedrals, abbeys and churches of Europe. It is also the architecture of many castles, palaces, town halls, guild halls, universities and to a less prominent extent, private dwellings, such as dorms and rooms.

Façade of Reims Cathedral, France

Façade of Reims Cathedral, FranceIt is in the great churches and cathedrals and in a number of civic buildings that the Gothic style was expressed most powerfully, its characteristics lending themselves to appeals to the emotions, whether springing from faith or from civic pride. A great number of ecclesiastical buildings remain from this period, of which even the smallest are often structures of architectural distinction while many of the larger churches are considered priceless works of art and are listed with UNESCO as World Heritage Sites. For this reason a study of Gothic architecture is largely a study of cathedrals and churches.

The interior of the western end of Reims Cathedral

The interior of the western end of Reims CathedralA series of Gothic revivals began in mid-18th-century England, spread through 19th-century Europe and continued, largely for ecclesiastical and university structures, into the 20th century.

Overview of Reims Cathedral from north-east

Overview of Reims Cathedral from north-eastLet's go Goth! A new cathedral design points to the heavens.

Pre-Built Course Content

EXPLORE ACTIVITIES

Angkor and Benin –Southeast Asia and West Africa

- Chapter 11 (pp. 375-6), Angkor Wat (in Cambodia), history and connections to Hindu beliefs; (pp. 386-7), Benin (in Nigeria, West Africa); Review "Week 6 Music" folder

- Content blocked:

- Video on Angkor Wat at http://video.nationalgeographic.com/video/specials/ancient-mysteries/angkor-wat-temples/

Angkor Wat (Khmer: អង្គរវត្ត or "Capital Temple") is a temple complex in Cambodia and the largest religious monument in the world, with site measuring 162.6 hectares (1,626,000 sq meters).[1] It was originally constructed as a Hindu temple for the Khmer Empire, gradually transforming into a Buddhist temple toward the end of the 12th century.[2] It was built by the Khmer King Suryavarman II[3] in the early 12th century in Yaśodharapura (Khmer: យសោធរបុរៈ, present-day Angkor), the capital of the Khmer Empire, as his state temple and eventual mausoleum. Breaking from the Shaiva tradition of previous kings, Angkor Wat was instead dedicated to Vishnu. As the best-preserved temple at the site, it is the only one to have remained a significant religious center since its foundation. The temple is at the top of the high classical style of Khmer architecture. It has become a symbol of Cambodia,[4] appearing on its national flag, and it is the country's prime attraction for visitors.

Angkor Wat combines two basic plans of Khmer temple architecture: the temple-mountain and the later galleried temple. It is designed to represent Mount Meru, home of the devas in Hindu mythology: within a moat and an outer wall 3.6 kilometres (2.2 mi) long are three rectangular galleries, each raised above the next. At the centre of the temple stands a quincunx of towers. Unlike most Angkorian temples, Angkor Wat is oriented to the west; scholars are divided as to the significance of this. The temple is admired for the grandeur and harmony of the architecture, its extensive bas-reliefs, and for the numerous devatas adorning its walls.

The modern name, Angkor Wat, means "Temple City" or "City of Temples" in Khmer; Angkor, meaning "city" or "capital city", is a vernacular form of the word nokor (នគរ), which comes from the Sanskrit word nagara (Devanāgarī: नगर).[5] Wat is the Khmer word for "temple grounds", also dervied from Sanskrit vāṭa (Devanāgarī: वाट), meaning "enclosure".[6]

Angkor Wat, 4:16

https://youtu.be/zBSk55K5CSk

Benin City is a city (2006 est. pop. 1,147,188) and the capital of Edo State in southern Nigeria. It is a city approximately 40 kilometres (25 mi) north of the Benin River. It is situated 320 kilometres (200 mi) by road east of Lagos. Benin is the centre of Nigeria's rubber industry, but processing palm nuts for oil is also an important traditional industry.[1]

- Benin City's history: See and http://africa.si.edu/exhibitions/current-exhibitions/alonge/history-of-benin/; (This city is in Nigeria; don't confuse it with the modern country called Benin not far away)

Gothic Style of Cathedral Architecture

- Chapter 12 (pp. 407-413), Stained glass windows; review Week 6 Music Folder

2: 56

-

Partly built starting in 1145, and then reconstructed over a 26-year period after the fire of 1194, Chartres Cathedral marks the high point of French Gothic art. The vast nave, in pure ogival style, the porches adorned with fine sculptures from the middle of the 12th century, and the magnificent 12th- and 13th-century stained-glass windows, all in remarkable condition, combine to make it a masterpiece.

- Stained glass windows at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9727p6ozlYo

- Key differences between Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D20tG65TWic

Pre-Built Course Content

HUM111 Music for Week 6

In this week's readings (chaps. 11-12), there are three musical compositions mentioned. These (or decent equivalents) can be found on YouTube. Watch and give it a listen. Here below is some background and description of each--and the links to the YouTubes (and sometimes other helps).

West Africa: Yoruba Traditional Talking Drums (chap. 11, p. 387), 5:32

The music of the Yoruba people is perhaps best known for an extremely advanced drumming tradition,[88] especially using the dundun[89] hourglass tension drums. The representation of musical instruments on sculptural works from Ile-Ife, indicates, in general terms a substantial accord with oral traditions. A lot of these musical instruments date back to the classical period of Ile-Ife, which began at around the 10th century A.D. Some were already present prior to this period, while others were created later. The hourglass tension drum (Dùndún) for example, may have been introduced around the 15th century (1400's), the Benin bronze plaques of the middle period depicts them. Others like the double and single iron clapper-less bells are examples of instruments that preceded classical Ife.[90] Yoruba folk music became perhaps the most prominent kind of West African music in Afro-Latin and Caribbean musical styles. Yorùbá music left an especially important influence on the music of Trinidad, the Lukumi religious traditions,[91] practice and the music of Cuba.[92]

Royal Gbèdu drums

Today, the word Gbedu has also come to be used to describe forms of Nigerian Afrobeat and Hip Hop music. The fourth major family of Yoruba drums is the Bàtá family which are well decorated double faced drums, with various tones. They were historically played in sacred rituals. They are believed to have been introduced by Shango, an Orisha, during his earthly incarnations as a warrior king. Traditional Yoruba drummers are known as Àyán. The Yoruba believe that Àyángalúwas the first drummer. He is also believed to be the spirit or muse that inspires drummers during renditions. This is why some Yoruba family names contain the prefix 'Ayan-' such as Ayangbade, Ayantunde, Ayanwande.[94] Ensembles using the dundun play a type of music that is also called dundun.[89] The Ashiko (Cone shaped drums), Igbin, Gudugudu (Kettledrums in the Dùndún family), Agidigbo and Bèmbé are other drums of importance. The leader of a dundun ensemble is the oniyalu meaning; ' Owner of the mother drum ', who uses the drum to "talk" by imitating the tonality of Yoruba. Much of this music is spiritual in nature, and is often devoted to the Orisas.

Agogo metal gongs

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HUuykOe9doU (see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B4oQJZ2TEVI&list=PLF7DC628F7164F441 [6:02] for discussion of the traditional form.

Cf. King Sunny Ade & His African Beats - Me Le Se (Live on KEXP), 7:43

"King" Sunny Adé (born Sunday Adeniyi, 22 September 1946) is a Nigerian musician, singer-songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, and a pioneer of modern world music. He has been classed as one of the most influential musicians of all time.[1]

Refer to http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=osNAy1DNkOQ&list=RDZedutGxrkAw for modernized version)

The Yoruba tribe of West Africa uses three types of batá drums to do musical signaling that simulates Yoruba talking. Read p. 387 (in chap. 11) carefully about the background of this "Talking Drum" music and then listen to the YouTubes at the links above.

----------------------

Alleluia, Dies Sanctificatus (chap. 12, p. 417; compare chap. 10, p. 347) Léonin (this selection was also in Week 5; it is discussed in both chapters 10 and 12)

Léonin (also Leoninus, Leonius, Leo) (fl. 1150s — d. ? 1201) was the first known significant composer of polyphonic organum. He was probably French, probably lived and worked in Paris at the Notre Dame Cathedral and was the earliest member of the Notre Dame school of polyphony and the ars antiqua style who is known by name. The name Léonin is derived from "Leoninus," which is the Latin diminutive of the name Leo; therefore it is likely that Léonin's given French name was Léo.

All that is known about him comes from the writings of a later student at the cathedral known as Anonymous IV, an Englishman who left a treatise on theory and who mentions Léonin as the composer of the Magnus Liber, the "great book" of organum. Much of the Magnus Liber is devoted to clausulae—melismatic portions of Gregorian chant which were extracted into separate pieces where the original note values of the chant were greatly slowed down and a fast-moving upper part is superimposed. Léonin might have been the first composer to use the rhythmic modes, and maybe he invented a notation for them. According to W.G. Waite, writing in 1954: "It was Léonin's incomparable achievement to introduce a rational system of rhythm into polyphonic music for the first time, and, equally important, to create a method of notation expressive of this rhythm."[1]

The Magnus Liber was intended for liturgical use. According to Anonymous IV, "Magister Leoninus (Léonin) was the finest composer of organum; he wrote the great book (Magnus Liber) for the gradual and antiphoner for the sacred service." All of the Magnus Liber is for two voices, although little is known about actual performance practice: the two voices were not necessarily soloists.

According to Anonymous IV, Léonin's work was improved and expanded by the later composer Pérotin. See also Medieval music.

The musicologist Craig Wright believes that Léonin may have been the same person as a contemporaneous Parisian poet, Leonius, after whom Leonine verse may have been named. This could make Léonin's use of meter even more significant.[2]

4:23

The mystery of the Incarnation of the Word lies at the heart of the Christian faith. It is celebrated just after the longest night of the year, when (in the northern hemisphere) the days begin to lengthen until we reach the summer solstice, which is associated with the figure of John the Baptist. To celebrate this moment, the Church deploys an exceptional virtually uninterrupted liturgical cycle in which the usual Offices are interspersed with four Masses.

The music is that of the ancient chant of the Church of Rome, one of the oldest repertories of which traces have remained in the collective memory of mankind. Up to the thirteenth century this repertory accompanied the papal liturgy. It disappeared with the installation of the papacy in Avignon, and sank into oblivion. Rediscovered in the early twentieth century, it aroused little enthusiasm among musicians, and only began to be studied properly, first from the liturgical, then from the musicological perspective, in the second half of the century. At this time, to distinguish it from Gregorian chant, it was named Old Roman chant.

Old Roman chant occupies a central position in the history of music. It is the keystone which gives meaning and coherence to what ought to be the musical consciousness of Western Europe and far beyond. For, looking back to the period before, it gives us the key to the filiation between the chant of the Temple of Jerusalem and the heritage of Greek music. Through the magic of music, sung texts become icons. Time is deployed with sovereign slowness confers on the sound a hieratic immanence in which time and space are united in a single vibrant truth.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wBs-qf8AUCc (for text and translation, see http://williamhawley.net/scorepages/alleluiadies/alleluiadiestxt.htm )

Polyphony

In music, polyphony is a texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice which is called monophony, and in difference from musical texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chords which is called homophony.

Within the context of the Western musical tradition, the term is usually used to refer to music of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. Baroque forms such as fugue, which might be called polyphonic, are usually described instead as contrapuntal. Also, as opposed to the species terminology of counterpoint, polyphony was generally either "pitch-against-pitch" / "point-against-point" or "sustained-pitch" in one part with melismas of varying lengths in another.[1] In all cases the conception was probably what Margaret Bent (1999) calls "dyadic counterpoint",[2] with each part being written generally against one other part, with all parts modified if needed in the end. This point-against-point conception is opposed to "successive composition", where voices were written in an order with each new voice fitting into the whole so far constructed, which was previously assumed.

The term polyphony is also sometimes used more broadly, to describe any musical texture that is not monophonic. Such a perspective considers homophony as a sub-type of polyphony.[3]

Melismatic

Melisma (Greek: μέλισμα, melisma, song, air, melody; from μέλος, melos, song, melody), plural melismata, in music, is the singing of a single syllable of text while moving between several different notes in succession. Music sung in this style is referred to as melismatic, as opposed to syllabic, in which each syllable of text is matched to a single note.

Read p. 417 (in chap. 12) carefully, and then briefly glance back at p. 347 (in chap. 10). Then consider the term polyphony (two or more lines of melody; p. 347) as you listen to this, as well as the other terms suggested.This selection is a partricular form called “melismatic”. The composer (Léonin) worked in the Notre Dame Cathedral (Paris) in the late 1100s AD. Alleluia, Dies Sanctificatus (="Hallelujah, A Holy Day") is a chant normally sung at Christmas. This was one of the polyphonic chants in Léonin’s Magnus Liber Organi (his “Big Book of Polyphony”!). You can see how chant is developing even further from those examples in the earlier chants covered in Week 5.

Viderunt Omnes (by Pérotin) (chap. 12, pp. 417-418), 11:50

"Viderunt Omnes" is a traditional Gregorian chant of the 11th century. The work is based on an ancient gradual of the same title.

The chant was subsequently expanded upon by composers of the Notre Dame school who developed it as type of early polyphony known as organum. Thought to be written for Christmas, the polyphonic settings would have retained the same liturgical purpose as the original gradual, while being musically enhanced for the festivities. The cantus firmus, or tenor, "holds" the original chant, while the other parts develop complex melismas on the vowels. The various settings of Viderunt Omnes provide context for specific trends in medieval music.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KA6oq_UYbyA

This polyphonic composition by Pérotin was designed for singing in a large Gothic cathedral in the late 1100s and early 1200s AD. Our book notes the use of “counterpoint”. Viderunt Omnes (="All Have Seen"). See p. 418 for the Latin lyrics and translation.

Gothic Cathedrals

Birth of the Gothic, Abbot Suger and the ambulatory in the Basilica of St. Denis, 1140-44, 5:17

More free lessons at: http://www.khanacademy.org/video?v=2E... Ambulatory, Basilica of Saint Denis, Paris, 1140-44.

Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

http://youtu.be/2EciWH-1ya4

Chartres Cathedral

Chartres Cathedral, also known as Cathedral of Our Lady of Chartres (French: Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Chartres), is a medieval Catholic cathedral of the Latin Church located in Chartres, France, about 80 kilometres (50 mi) southwest of Paris. It is considered one of the finest examples of French Gothic architecture and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The current cathedral, mostly constructed between 1194 and 1250, is the last of at least five which have occupied the site since the town became a bishopric in the 4th century.

The cathedral is in an exceptional state of preservation. The majority of the original stained glass windows survive intact, while the architecture has seen only minor changes since the early 13th century. The building's exterior is dominated by heavy flying buttresses which allowed the architects to increase the window size significantly, while the west end is dominated by two contrasting spires – a 105-metre (349 ft) plain pyramid completed around 1160 and a 113-metre (377 ft) early 16th-century Flamboyant spire on top of an older tower. Equally notable are the three great façades, each adorned with hundreds of sculpted figures illustrating key theological themes and narratives.

Since at least the 12th century the cathedral has been an important destination for travellers – and remains so to this day, attracting large numbers of Christian pilgrims, many of whom come to venerate its famous relic, the Sancta Camisa, said to be the tunic worn by the Virgin Mary at Christ's birth, as well as large numbers of secular tourists who come to admire the cathedral's architecture and historical merit.

One of the most beautiful and mysterious cathedrals in the world is the famous Chartres Cathedral in Chartres, France.

Forty-four magnificent stained-glass windows, including three rose windows, tell the story of the world from creation to the day of judgment. The 12th Century labyrinth in the nave paving is the largest and best preserved surviving example of a medieval labyrinth in France.

Who were the architects, the so called Masters of the Compasses? Where did they get the courage and confidence to build such a complex and magnificent cathedral as Chartres?

18 Chartres Cathedral Part 2 - Secrets in Plain Sight 4:55

Secrets In Plain Sight is an awe inspiring exploration of great art, architecture, and urban design which skillfully unveils an unlikely intersection of geometry, politics, numerical philosophy, religious mysticism, new physics, music, astronomy, and world history.

Exploring key monuments and their positions in Egypt, Stonehenge, Jerusalem, Rome, Paris, London, Edinburgh, Washington DC, New York, and San Francisco brings to light a secret obsession shared by pharaohs, philosophers and kings; templars and freemasons; great artists and architects; popes and presidents, spanning the whole of recorded history up to the present time.

As the series of videos reveals how profound ancient knowledge inherited from Egypt has been encoded in units of measurement, in famous works of art, in the design of major buildings, in the layout of city streets and public spaces, and in the precise placement of obelisks and other important monuments upon the Earth, the viewer is led to perceive an elegant harmonic system linking the human body with the architectural, urban, planetary, solar, and galactic scales.

https://youtu.be/wfObQbY2Tww

Rise of the University

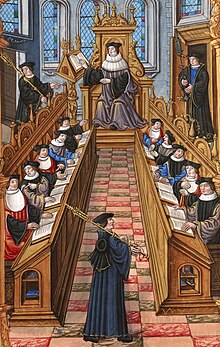

Augustine of Hippo’s On Christian Doctrine was required reading, as were Boethius’s writings on music and arithmetic. To obtain their bachelor of arts (BA) degree, students took oral exams after three to five years of study. Further study to acquire mastery of a special field led to the master of arts (MA) degree and might qualify a student to teach theology or practice medicine or law. Four more years of study were required to acquire the title of doctor (from the Latin, doctus, “learned”), culminating in a defense of a thesis before a board of learned examiners.

The University of Paris was chartered in 1200, and soon after came Oxford and Cambridge universities in England. These northern universities emphasized the study of theology. In Paris, a house or college system was organized, at first to provide students with housing and then to help them focus their education. The most famous of these was organized by Robert de Sorbon in 1257 for theology students. The Sorbonne, named after him, remains today the center of Parisian student life.

European higher education took place for hundreds of years in Christian cathedral schools or monastic schools (scholae monasticae), in which monks and nuns taught classes; evidence of these immediate forerunners of the later university at many places dates back to the 6th century.[10] The earliest universities were developed under the aegis of the Latin Church by papal bull as studia generalia and perhaps from cathedral schools. It is possible, however, that the development of cathedral schools into universities was quite rare, with the University of Paris being an exception.[11] Later they were also founded by Kings (University of Naples Federico II, Charles University in Prague, Jagiellonian University in Kraków) or municipal administrations (University of Cologne, University of Erfurt). In the early medieval period, most new universities were founded from pre-existing schools, usually when these schools were deemed to have become primarily sites of higher education. Many historians state that universities and cathedral schools were a continuation of the interest in learning promoted by monasteries.[12]

The first universities in Europe with a form of corporate/guild structure were the University of Bologna (1088), the University of Paris (c. 1150, later associated with the Sorbonne), and the University of Oxford (1167).

The University of Bologna began as a law school teaching the ius gentium or Roman law of peoples which was in demand across Europe for those defending the right of incipient nations against empire and church. Bologna's special claim to Alma Mater Studiorum[clarification needed] is based on its autonomy, its awarding of degrees, and other structural arrangements, making it the oldest continuously operating institution[7] independent of kings, emperors or any kind of direct religious authority.[13][14]

Meeting of doctors at the University of Paris. From a medieval manuscript.

In Europe, young men proceeded to university when they had completed their study of the trivium–the preparatory arts of grammar, rhetoric and dialectic or logic–and the quadrivium: arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy.

All over Europe rulers and city governments began to create universities to satisfy a European thirst for knowledge, and the belief that society would benefit from the scholarly expertise generated from these institutions. Princes and leaders of city governments perceived the potential benefits of having a scholarly expertise develop with the ability to address difficult problems and achieve desired ends. The emergence of humanism was essential to this understanding of the possible utility of universities as well as the revival of interest in knowledge gained from ancient Greek texts.[18]

The rediscovery of Aristotle's works–more than 3000 pages of it would eventually be translated –fuelled a spirit of inquiry into natural processes that had already begun to emerge in the 12th century. Some scholars believe that these works represented one of the most important document discoveries in Western intellectual history.[19] Richard Dales, for instance, calls the discovery of Aristotle's works "a turning point in the history of Western thought."[20] After Aristotle re-emerged, a community of scholars, primarily communicating in Latin, accelerated the process and practice of attempting to reconcile the thoughts of Greek antiquity, and especially ideas related to understanding the natural world, with those of the church. The efforts of this "scholasticism" were focused on applying Aristotelian logic and thoughts about natural processes to biblical passages and attempting to prove the viability of those passages through reason. This became the primary mission of lecturers, and the expectation of students.

Sapienza University of Rome is the largest university in Europe and one of the most prestigious European universities.[21]

Their endowment by a prince or monarch and their role in training government officials made these Mediterranean universities much different to Islamic madrasas, controlled as they were by a religious authority. Madrasas were generally smaller and individual teachers, rather than the madrasa itself, granted the license or degree.[25] A minority view, represented by scholars like Arnold H. Green and Hossein Nasr have argued that starting in the 10th century, some medieval Islamic madrasahs became universities.[26][27] None of the madrasahs blossomed into an institution such as a medieval, European University. George Makdisi and others,[28] in fact, argue that the European university has no parallel in the medieval Islamic world.[29]

Numerous other scholars regard the university as uniquely European in origin and characteristics.[30][31]

Many scholars (including Makdisi) have argued that early medieval universities were influenced by the religious madrasahs in Al-Andalus, the Emirate of Sicily, and the Middle East (during the Crusades).[32][33][34] The majority view of scholars see this argument as overstated.[35] Lowe and Yasuhara have recently drawn on the well-documented influences of scholarship from the Islamic world on the universities of Western Europe to call for a reconsideration of the development of higher education, turning away from a concern with local institutional structures to a broader consideration within a global context.[36]

An important idea in the definition of a university is the notion of academic freedom. The first documentary evidence of this comes from early in the life of the first university. The University of Bologna adopted an academic charter, the Constitutio Habita,[6] in 1158 or 1155,[7] which guaranteed the right of a traveling scholar to unhindered passage in the interests of education. Today this is claimed as the origin of "academic freedom".[8] This is now widely recognised internationally [except in the Islamic Middle East] - on 18 September 1988 430 university rectors signed the Magna Charta Universitatum,[9] marking the 900th anniversary of Bologna's foundation. The number of universities signing the Magna Charta Universitatum continues to grow, drawing from all parts of the world.

One important way to contrast an early madrassah with a modern University is to compare them.

Al-Azhar University (AHZ-har; Arabic: جامعة الأزهر (الشريف) Jāmiʻat al-Azhar (al-Sharīf), IPA: [ˈɡæmʕet elˈʔɑzhɑɾ eʃʃæˈɾiːf], "the (honorable) Azhar University") is a university in Cairo, Egypt. Associated with Al-Azhar Mosque in Islamic Cairo, it is Egypt's oldest degree-granting university and is renowned as "Sunni Islam’s most prestigious university".[1] In addition to higher education, Al-Azhar oversees a national network of schools with approximately two million students.[2] As of 1996, over 4000 teaching institutes in Egypt were affiliated with the University.[3]

Founded in 970 or 972 by the Fatimids as a centre of Islamic learning, its students studied the Qur'an and Islamic law in detail, along with logic, grammar, rhetoric, and how to calculate the lunar phases of the moon. It is today the chief centre of Arabic literature and Islamic learning in the world.[4] In 1961 additional non-religious subjects were added to its curriculum.[5]

Its mission is to propagate Islam and Islamic culture. To this end, its Islamic scholars (ulamas) render edicts (fatwas) on disputes submitted to them from all over the Sunni Islamic world regarding proper conduct for Muslim individuals and societies. Al-Azhar also trains Egyptian government-appointed preachers in proselytization (da'wa).

Its library is considered second in importance in Egypt only to the Egyptian National Library and Archives. In May 2005, Al-Azhar in partnership with a Dubai information technology enterprise, IT Education Project (ITEP) launched the H.H. Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum Project to Preserve Al Azhar Scripts and Publish Them Online (the "Al-Azhar Online Project") with the mission of eventually providing online access to the library's entire rare manuscripts collection (comprising about seven million pages).[6][7]

A "University" in the Islamic world is much closer to what in the West we would call a seminary which promotes theological dogma.

In point of contrast, freedom of thought is not encouraged at an Islamic University.

In October 2007, Muhammad Sayyid Tantawy, then the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, drew allegations of stifling freedom of speech when he asked the Egyptian government to toughen its rules and punishments against journalists. During a Friday sermon in the presence of Egyptian Prime Minister Ahmed Nazif and a number of ministers, Tantawy was alleged to have stated that journalism which contributes to the spread of false rumours rather than true news deserved to be boycotted, and that it was tantamount to sinning for readers to purchase such newspapers. Tantawy, a supporter of then Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, also called for a punishment of eighty lashes to "those who spread rumors" in an indictment of speculation by journalists over Mubarak's ill health and possible death.[25][26] This was not the first time that he had criticized the Egyptian press regarding its news coverage nor the first time he in return had been accused by the press of opposing freedom of speech. During a religious celebration in the same month, Tantawy had released comments alluding to "the arrogant and the pretenders who accuse others with the ugliest vice and unsubstantiated charges". In response, Egypt's press union issued a statement suggesting that Tantawy appeared to be involved in inciting and escalating a campaign against journalists and freedom of the press.[27]

We can not imagine that a Western University, e.g., a modern Catholic University, would advocate lashes for journalists; however, this is common in modern Islamic Universities. In addition, the course of study at an Islamic University does not include Western subjects, or non-Muslim religions.

Héloïse and Abelard

The quality of its teaching most distinguished the University of Paris. Because books were available only in handwritten manuscripts, they were extremely expensive, so students relied on lectures and copious note-taking for their instruction. Peter Abelard (1079–ca. 1144), a brilliant logician and author of the treatise Sic et Non (“Yes and No”), was one of the most popular lecturers of his day. Crowds of students routinely gathered to hear him. He taught by the dialectical method—that is, by presenting different points of view and seeking to reconcile them. This method of teaching originates in the Socratic method, but whereas Socratic dialogue consisted of a wise teacher who was questioned by students, or even fools, Abelard’s dialectical method presumed no such hierarchical relationships. Everything, to him, was open to question. “By doubting,” he famously argued, “we come to inquire, and by inquiring we arrive at truth.”

Needless to say, the Church found it difficult to deal with Abelard, who demonstrated time and again that various Church Fathers—and the Bible itself—held hopelessly opposing views on many issues. Furthermore, the dialectical method itself challenged the unquestioning faith in God and the authority of the Church. Abelard was particularly opposed by Bernard of Clairvaux, who in 1140 successfully prosecuted him for heresy. By then, Abelard’s reputation as a teacher had not faded, but his moral position had long been suspect. In 1119, he had pursued a love affair with his private student, Héloïse. Abelard not only felt that he had betrayed a trust by falling in love with her and subsequently impregnating her, but he was further humiliated by Héloïse’s angry uncle, in whose home he had tutored and seduced the girl. Learning of the pregnancy, the uncle hired thugs to castrate Abelard in his bed. Abelard retreated to the monastery at Saint-Denis, accepting the protection of the powerful Abbot Suger. Héloïse joined a convent and later served as abbess of Paraclete, a chapel and oratory founded by Abelard.

Famous Love Stories: The Letters of Abelard and Heloise, 4:18

https://youtu.be/0NY75SqBrDo

Medieval era

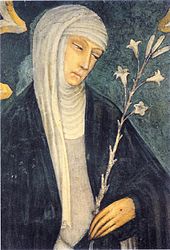

St. Clare of Assisi played an important role in the 13th century Franciscan movement.

Doctor of the Church St. Catherine of Sienna was an influential 14th-century theologian who worked to bring the Avignon Papacy back to Rome.

St. Joan of Arc led a French military campaign against the English.

St. Teresa of Ávila, a 16th-century Doctor of the Church, is considered one of the most important Catholic mystics.[11]

Depiction by Rubens, 1615

Blainey cites the ever growing veneration of the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene as evidence of a high standing for female Christians at that time. The Virgin Mary, was conferred such titles as Mother of God and Queen of Heaven and, in 863, her feast day, the "Feast of Our Lady", was declared equal in importance to those of Easter and Christmas. Mary Magdalene's Feast Day was celebrated in earnest from the 8th century and composite portraits of her were built up from Gospel references to other women Jesus met.[14]

According to historian Shulamith Shahar, "[s]ome historians hold that the Church played a considerable part in fostering the inferior status of women in medieval society in general" by providing a "moral justification" for male superiority and by accepting practices such as wife-beating.[15] Despite these laws, some women, particularly abbesses, gained powers that were never available to women in previous Roman or Germanic societies.[16]

Although historians have argued that church teachings emboldened secular authorities to give women fewer rights than men, they also helped form the concept of chivalry.[17] Chivalry was influenced by a new Church attitude towards Mary, the mother of Jesus.[18] This "ambivalence about women's very nature" was shared by most major religions in the Western world.[19] The development of Marian devotions and the image of the Virgin Mary as the "second Eve" also influenced the status of women during the Middle Ages. The increasing popularity of devotion to the Virgin Mary (the mother of Jesus) secured maternal virtue as a central cultural theme of Catholic Europe. Art historian Kenneth Clarke wrote that the 'Cult of the Virgin' in the early 12th century "had taught a race of tough and ruthless barbarians the virtues of tenderness and compassion".[20]

Women who had been looked down upon as daughters of Eve, came to be regarded as objects of veneration and inspiration. The medieval development of chivalry, with the concept of the honor of a lady and the ensuing knightly devotion to it, was derived from Mariological thinking, and contributed to it.[21] The medieval veneration of the Virgin Mary was contrasted to disregard for ordinary women, especially those outside aristocratic circles. At a time when women could be viewed as the source of evil, the concept of the Virgin Mary as mediator to God positioned her as a source of refuge for man, affecting the changing attitudes towards women.[22]

In Celtic Christianity, abbesses could preside over houses containing both monks and nuns (male and female religious), a practice brought to continental Europe by Celtic missionaries.[23] Irish hagiography holds that, as Europe was entering the Medieval Age, the abbess Brigit of Kildare was founding monasteries across Ireland. The Celtic Church played an important role in restoring Christianity to Western Europe following the Fall of Rome, thus the work of nuns like Brigid is significant in Christian history.[24]

Leading churchwomen held a high rank within medieval society. Abbesses, as female superiors of monastic houses, were powerful figures whose influence could rival that of male bishops and abbots: "They treated with kings, bishops, and the greatest lords on terms of perfect equality;. . . they were present at all great religious and national solemnities, at the dedication of churches, and even, like the queens, took part in the deliberation of the national assemblies...".[25] In England, abbesses of major houses attended all great religious and national solemnities, such as deliberations of the national assemblies and ecclesiastical councils. In Germany the major abbesses were ranked among the princes of the Empire, enabling them to sit and vote in the Diet. They lived in fine estates, and recognised no church superior save the Pope. Similarly in France, Italy and Spain, female superiors could be very powerful figures.[26]

In the important Franciscan movement of the 13th century, a significant part was played by women religious. Clare of Assisi was one of the first followers of Saint Francis of Assisi. She founded the Order of Poor Ladies, a contemplative monastic religious order for women in the Franciscan tradition, and wrote their Rule of Life—the first monastic rule known to have been written by a woman. Following her death, the order she founded was renamed in her honor as the Order of Saint Clare, commonly referred to today as the Poor Clares.[27]

Catherine of Sienna (1347–1380) was a Dominican tertiary and mystic of considerable influence who was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church in 1970. Considered by her contemporaries to have high levels of spiritual insight, she worked with the sick and poor, experienced "visions", gathered disciples, and participated in the highest levels of public life through corresponding with the princes of Italy, consulting with papal legates, and acting as a diplomat negotiating among the city states of Italy. She counseled for reform of the clergy and was influential in convincing Pope Gregory XI to leave Avignon and restore the Holy See to Rome.[28]

According to Bynum, during the 12th-15th centuries there was an unprecedented flowering of mysticism among female members of religious orders in the Catholic Church. Petra Munro describes these women as "transgressing gender norms" by violating the dictates of the Apostle Paul that "women should not speak, teach or have authority" (1 Timothy 2:12). Munro notes that, although the number of female mystics was "significant", we tend to be more familiar with male figures such as Augustine of Hippo, Bernard of Clairvaux, Francis of Assisi, Thomas Acquinas or Meister Eckhart than with Hildegard of Bingen, Julian of Norwich, Mechthild of Magdeburg, Hadewijch of Antwerp or Teresa of Avila.[12]

An example is provided by the 12th-century Speculum Virginum (Mirror of Virgins in Latin) document which provides one of the earliest comprehensive theologies of cloistered religious life.[29] The growth of the various manuscripts of the Speculum Virginum in the Middle Ages had a particular resonance for women who sought a dedicated religious life. Yet, its effect on the development of female monastic life also influenced the proliferation of male monastic orders.[30] These monastic orders came to include key Catholic figures such as Teresa of Ávila, now recognized as a Doctor of the Church, whose influence on practices such as Christian meditation has continued.[11][31][32]

Arguably the most famous female Catholic saint of the period is Joan of Arc. Considered a national heroine of France, she began life as a pious peasant girl. As with other saints of the period, Joan is said to have experienced supernatural dialogues that gave her spiritual insight and directed her actions. But, unlike typical heroines of the period, she donned male attire and, claiming divine guidance, sought out King Charles VII of France to offer help in a military campaign against the English. Taking up a sword, she achieved military victories before being captured. Her English captors and their Burgundian allies arranged for her to be tried as a "witch and heretic", after which she was convicted and burned at the stake. A papal inquiry later declared the trial illegal. A hero to the French, Joan inspired sympathy even in England, and in 1909 she was canonised as a Catholic saint.[33] She remains an important figure in Western culture.

Catholic monarchs

Saint Jadwiga of Poland is the patron saint of queens.

Saint Elizabeth of Portugal, a famous Franciscan tertiary.

Queen Isabella I of Castille (Isabella the Catholic) helped unify Spain and spread Catholicism to the Americas.

Maria Theresa of Austria was Holy Roman Empress and a powerful figure in Central European politics.

As sponsor of Christopher Columbus' 1492 mission to cross the Atlantic, the Spanish Queen Isabella I of Castille (known as Isabella the Catholic), was an important figure in the growth of Catholicism as a global religion. Spain and Portugal sent explorers and settlers to follow Columbus' route and establish vast Empires in the Americas, where they converted Native Americans to Catholicism. Her marriage to Ferdinand II of Aragon had ensured the unity of the Spanish Kingdom and the royal couple agreed to hold equal authority. Spanish Pope Alexander VI conferred on them the title "Catholic". As part of legal reforms to consolidate their authority, Isabella and Ferdinand instigated the Spanish Inquisition. The Catholic Monarchs then conquered the last Moorish bastion in Spain at Granada in January 1492 and seven months later, Columbus sailed for the Americas. The Catholic Encyclopedia credits Isabella as an extremely able ruler and one who "fostered learning not only in the universities and among the nobles, but also among women". Of Isabella and Ferdinand, it says: "The good government of the Catholic sovereigns brought the prosperity of Spain to its apogee, and inaugurated that country's Golden Age."[37]

The Reformation swept through Europe during the 16th Century, ending centuries of unity among Western Christendom and bringing Protestantism into being as both a religious and political opponent of Catholicism. For the first time in centuries, the religion of an heir to the throne became an intensely important political issue. After the refusal of Pope Clement VI to grant an annulment in the marriage of King Henry VIII to Catherine of Aragon, Henry established himself as supreme governor of the church in England. Rivalry between Catholic and Protestant heirs ensued. Mary I of England was his eldest daughter and succeeded the throne after the death of her Protestant younger half-brother Edward VI. Later nicknamed "Bloody Mary" for her actions against Protestants, she was the daughter of Catherine of Aragon; she remained loyal to Rome and sought to restore the Roman Church in England. Her re-establishment of Roman Catholicism was reversed after her death in 1558 by her successor and younger half-sister, Elizabeth I. Rivalry emerged between Elizabeth and the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots, finally settled with the execution of Mary in 1587. The religion of an heir or monarch's spouse complicated intermarriage between royal houses of Europe through coming centuries, as northern European nations became predominately Protestant.

Consorts of the Holy Roman Emperors were given the title of Holy Roman Empress. The throne was reserved for males, thus there was never a Holy Roman Empress regnant, though women such as Theophanu and Maria Theresa of Austria controlled the power of rule and served as de facto Empresses regnant. The powerful Maria Theresa acquired her right to the throne of the Habsburg dominions by means of the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713, allowing for female succession - but had to fight the War of the Austrian Succession to secure that right. Following victories, her husband, Francis Stephen, was chosen as Holy Roman Emperor in 1745, confirming Maria Theresa's status as a European leader. A liberal-minded autocrat, she was a patron of sciences and education and sought to alleviate the suffering of the serfs. On religion she pursued a policy of cujus regio, ejus religio, keeping Catholic observance at court and frowning on Judaism and Protestantism. The ascent of her son as co-regnant Emperor saw restrictions placed on the power of the Church in the Empire. She reigned for 40 years, and mothered 16 children including Marie-Antoinette, the ill-fated Queen of France.[38] With her husband she founded the Catholic Habsburg-Lorraine Dynasty, who remained central players in European politics into the 20th century.

Of the remaining European monarchies, all are now constitutional monarchies, with some still ruled by Catholic dynasties, including the Spanish and Belgian Royal Families and the House of Grimaldi. Many non-aristocratic Catholic women have served in public office in the modern era.

General Education & Teaching Tips : Women's Clothes in the Middle Ages 1:53

https://youtu.be/XwlKibJxKs0

Women's clothes in the Middle Ages were typically ornate and luxurious for noblewomen, with long sleeves, high waists and tall hats; but clothes were fairly simple for peasant women. Discover more about the clothing for women in the Middle Ages with advice from an educator in this free video on general education.

Expert: Laura Turner

Bio: Laura Turner received her B.A. in English from the University of the South in Sewanee, Tenn., graduating magna cum laude with honors. Her plays have been seen and heard from Alaska to Tennessee.

Filmmaker: Todd Green

The Catholic Church: Builder of Civilization - The University System, Ep 5 [Part 2], 9:56

EWTN's series on the Catholic Church, hosted by Dr. Thomas E. Woods, Jr.

The Catholic Church has long been the protector of knowledge and learning.

http://youtu.be/VMeFawTXhOQ

Who is the Dumb Ox?

An altarpiece in Ascoli Piceno, Italy,

An altarpiece in Ascoli Piceno, Italy,by Carlo Crivelli (15th century)

St. Thomas Aquinas, Genius and Saint, 2:53

Tommaso d'Aquino, OP (1225 – 7 March 1274), also known as Saint Thomas Aquinas (/əˈkwaɪnəs/), is a Doctor of the Church. He was an Italian[3][4] Dominican friar Roman Catholic priest, who was an immensely influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism, within which he is also known as the "Doctor Angelicus" and "Doctor Communis".[5] The name "Aquinas" identifies his ancestral origins in the county of Aquino (in the present-day Lazio region), an area where his family held land until 1137.

Thomas Aquinas and Scholasticism

In 1245, Thomas Aquinas (1225–74), a 20-year-old Dominican monk from Italy, arrived at the University of Paris to study theology, walking into a theological debate that had been raging for nearly 100 years, ever since the conflict between Abelard and Bernard: How does the believer come to know God? With the heart? With the mind? Or with both? Do we come to know the truth intuitively or rationally? Aquinas took on these questions directly and soon became the most distinguished student and lecturer at the university.

He was the foremost classical proponent of natural theology and the father of Thomism. His influence on Western thought is considerable, and much of modern philosophy developed or opposed his ideas, particularly in the areas of ethics, natural law, metaphysics, and political theory. Unlike many currents in the Church of the time,[6] Thomas embraced several ideas put forward by Aristotle—whom he called "the Philosopher"—and attempted to synthesize Aristotelian philosophy with the principles of Christianity.[7] The works for which he is best known are the Summa Theologica and the Summa contra Gentiles. His commentaries on Sacred Scripture and on Aristotle form an important part of his body of work.

Scholasticism, 3:04

https://youtu.be/f9GJYS1WOCM

Furthermore, Thomas is distinguished for his eucharistic hymns, which form a part of the Church's liturgy.[8]

The Catholic Church honors Thomas Aquinas as a saint and regards him as the model teacher for those studying for the priesthood, and indeed the highest expression of both natural reason and speculative theology. In modern times, under papal directives, the study of his works was long used as a core of the required program of study for those seeking ordination as priests or deacons, as well as for those in religious formation and for other students of the sacred disciplines (philosophy, Catholic theology, church history, liturgy, and canon law).[9]

Also honored as a Doctor of the Church, Thomas is considered the Catholic Church's greatest theologian and philosopher. Pope Benedict XV declared: "This (Dominican) Order ... acquired new luster when the Church declared the teaching of Thomas to be her own and that Doctor, honored with the special praises of the Pontiffs, the master and patron of Catholic schools."[10]

A brief story of the life of St Thomas Aquinas. Up to this day he is revered as the great Doctor of the Church for having delivered such crucial concepts for the development of sacred theology and church philosophy.

http://youtu.be/547O4Oum_Ak

THE RADIANT STYLE AND THE COURT OF LOUIS IX

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis, was a Capetian King of France who reigned from 1226 until his death. Louis was crowned in Reims at the age of 12, following the death of his father Louis VIII the Lion, although his mother, Blanche of Castile, ruled the kingdom until he reached maturity. During Louis's childhood, Blanche dealt with the opposition of rebellious vassals and put an end to the Albigensian crusade which had started 20 years earlier.

As an adult, Louis IX faced recurring conflicts with some of the most powerful nobles, such as Hugh X of Lusignan and Peter of Dreux. Simultaneously, Henry III of England tried to restore his continental possessions, but was defeated at the battle of Taillebourg. His reign saw the annexation of several provinces, notably Normandy, Maine and Provence.

Louis IX was a reformer and developed French royal justice, in which the king is the supreme judge to whom anyone is able to appeal to seek the amendment of a judgment. He banned trials by ordeal, tried to prevent the private wars that were plaguing the country and introduced the presumption of innocence in criminal procedure. To enforce the correct application of this new legal system, Louis IX created provosts and bailiffs.

According to his vow made after a serious illness, and confirmed after a miraculous cure, Louis IX took an active part in the Seventh and Eighth Crusade in which he died from dysentery. He was succeeded by his son Philip III.

Louis's actions were inspired by Christian values and Catholic devotion. He decided to punish blasphemy, gambling, interest-bearing loans and prostitution, and bought presumed relics of Christ for which he built the Sainte-Chapelle. He also expanded the scope of the Inquisition and ordered the burning of Talmuds. He is the only canonized king of France, and there are consequently many places named after him.

Last Words of Saint Louis IX, King of France, 1270, 7:44

King Louis IX, a saint and King of France, is well known for his exploits in the Crusades. He was also one of the most respected, trusted rulers of the thirteenth century. Here we take a look at his last words as he lay dying during the Eighth Crusade, left to his son, Philip III of France. This testament is found in Jean of Joinville's Life of Saint Louis.

http://youtu.be/abWzoFlLAXQ

The New Mendicant Orders

Aside from cathedrals, civic leaders also engaged in building projects for the new urban religious orders: the Dominicans, founded by the Spanish monk Dominic de Guzman (ca. 1170–1221), whose most famous theologian was Thomas Aquinas; and the Franciscans, founded by Francis of Assisi (ca. 1181–1226). Unlike the traditional Benedictine monastic order, which functioned apart from the world, the Dominicans and the Franciscans were reformist orders, dedicated to active service in the cities, especially among the common people. Their growing popularity reflected the growing crisis facing the mainstream Church, as isolation and apparent disregard for laypeople plagued it well into the sixteenth century.

Origins, Traditions, Rules and Connections, 5:23

Part I of the conversation between Conventual Franciscan Fr. Paul

Schloemer, OFM Conv., and Dominican Fr. Elias Henritzy, O.P., introduces

our speakers, and begins with St. Dominic, St. Francis.

https://youtu.be/PqdbvLgFVug

The Appeal of Saint Francis

Both the Dominican and Franciscan orders were sanctioned by Pope Innocent III (papacy 1198–1216). Innocent exercised papal authority as no pope had before him. He went so far as to claim that the pope was to the emperor as the sun was to the moon, a reference to the fact that the emperor received his “brilliance” (that is, his crown) from the hand of the pope. Innocent established the papacy as a self-sustaining financial and bureaucratic institution. He formalized the Church hierarchy, from pope to parish priest, and gave full sanction to the doctrine of transubstantiation (the belief that the bread and wine of sacrament become the true body and blood of Christ when consecrated by a priest), and also made annual confession and Easter communion mandatory for all adult Christians.

Saint Francis of Assisi (Italian: San Francesco d'Assisi); born Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, but nicknamed Francesco; 1181/1182 – October 3, 1226) was an Italian Catholic friar and preacher. He founded the men's Order of Friars Minor, the women’s Order of St. Clare, and the Third Order of Saint Francis for men and women not able to live the lives of itinerant preachers, followed by the early members of the Order of Friars Minor, or the monastic lives of the Poor Clares. Francis is one of the most venerated religious figures in history.

St. Francis Of Assisi HD, 2:43

https://youtu.be/qYynL7fH0P8