The presentation may contain content that is deemed objectionable to a particular viewer because of the view expressed or the conduct depicted. The views expressed are provided for learning purposes only, and do not necessarily express the views, or opinions, of Strayer University, your professor, or those participating in videos or other media.

Week 2 Checklist

- Complete and submit Week 2 Quiz 1 covering Chapters 21 and 22 - 40 Points

- Read the following from your textbook:

-

- Chapter 23: The Baroque Court – Europe; the Americas

- Chapter 24: The Rise of the Enlightenment in England

- Explore the Week 2 Music Folder

- View the Week 2 Lecture videos

- Do the Week 2 Explore Activities

- Participate in the Week 2 Discussion (choose only one (1) of the discussion options) - 20 Points

We will have a break: I will take roll, we will do our Discussion at 9:45 before you are dismissed.

All Hail the Sun King! I'm Painting If You're Paying, English Enlightenment: We Know More, Now What?

https://blackboard.strayer.edu/bbcswebdav/institution/HUM/112/1146/Week2/Lecture/lecture.html

A video clip from Neil Tyson, explaining how the Middle east suddenly went from a region of Science and development, into the socially backward land of today. 4:13

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UNh751L8Uec

Milton Friedman - Capitalism, Slavery and Colonialism, 5:22

Did western democracies gain their wealth through slavery and colonialism? Professor Friedman answers. http://www.LibertyPen.com Source: Milton Friedman Speaks Buy it: http://www.freetochoose.net/store/pro...

https://youtu.be/e-fTYCCbXZ4

As Islam fell behind the West scientifically, the regressive nature of Islam should be clear; moreover, as the West developed free institutions based on constitutional monarchs, and ultimately, liberal constitutions, the Muslim majority countries were still characterized by absolute or despotic monarchs. Despots or monarchs still rule the Middle East today.

Absolute monarchy or despotic monarchy is a monarchical form of government in which the monarch has absolute power among his or her people. An absolute monarch wields unrestricted political power over the sovereign state and its people. Absolute monarchies are often hereditary but other means of transmission of power are attested. Absolute monarchy differs from constitutional monarchy, in which a monarch's authority in a constitutional monarchy is legally bounded or restricted by a constitution.

In theory, the absolute monarch exercises total power over the land, yet in practice the monarchy is counterbalanced by political groups from among the social classes and castes of the realm, such as the aristocracy, clergy, and middle and lower classes.

Some monarchies have weak or symbolic legislatures and other governmental bodies that the monarch can alter or dissolve at will. Countries where the monarch still maintains absolute power are Brunei,[4] Qatar,[5] Oman,[6] Saudi Arabia,[7] Swaziland,[8] the emirates comprising the United Arab Emirates,[9] and Vatican City.[10]

Did Obama Bow to Saudi King? :12

https://youtu.be/9WlqW6UCeaY

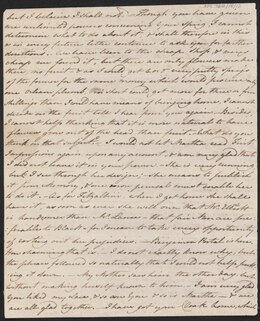

Fig. 23.1 Hyacinthe Rigaud, Louis XIV, King of France. 1701

Oil on canvas, 9'1" × 6'4⅜". Musée du Louvre, Paris. In his ermine coronation robes, his feet adorned in shoes with high, red heels, Louis both literally and figuratively looks down his nose at the viewer, his sense of superiority fully captured by Rigaud.

Who should Americans bow to?

What contrast can be drawn between the "Sun King" and George Washington?

Who should Americans bow to?

What contrast can be drawn between the "Sun King" and George Washington?

George Washington, in prayer before battle.

All Hail the Sun King!

I'm Painting if You're Paying

English Enlightenment: We Know More, Now What?

Pre-Built Course Content

https://blackboard.strayer.edu/bbcswebdav/institution/HUM/112/1146/Week2/Lecture/lecture.html

HUM112 Music Clips for Week 2

In this week's readings (chaps. 23-24), there are several musical compositions mentioned, especially on pp. 751-753, 757 (in chap. 23) and p. 790 (in chap. 24). These (or decent equivalents) can be found on YouTube. Watch and give them a listen. Here below is some background with description of each--and the link to the YouTube (and sometimes other helps).

Jean-Baptiste Lully (French: [ʒɑ̃ ba.tist ly.li]; born Giovanni Battista Lulli [dʒoˈvanni batˈtista ˈlulli]; 28 November 1632 – 22 March 1687) was an Italian-born French composer, instrumentalist, and dancer who spent most of his life working in the court of Louis XIV of France. He is considered a master of the French baroque style. Lully disavowed any Italian influence in French music of the period. He became a French subject in 1661.

Armide is an opera by Jean-Baptiste Lully. The libretto by Philippe Quinault is based on Torquato Tasso's poem La Gerusalemme liberata (Jerusalem Delivered). The work is in the form of a tragédie en musique, a genre invented by Lully and Quinault.

Critics in the 18th century regarded Armide as Lully's masterpiece. It continues to be well-regarded, featuring some of the best-known music in French baroque opera and being arguably ahead of its time in its psychological interest. Unlike most of his operas, Armide concentrates on the sustained psychological development of a character — not Renaud, who spends most of the opera under Armide's spell, but Armide, who repeatedly tries without success to choose vengeance over love.

Jean-Baptiste Lully (French: [ʒɑ̃ ba.tist ly.li]; born Giovanni Battista Lulli [dʒoˈvanni batˈtista ˈlulli]; 28 November 1632 – 22 March 1687) was an Italian-born French composer, instrumentalist, and dancer who spent most of his life working in the court of Louis XIV of France. He is considered a master of the French baroque style. Lully disavowed any Italian influence in French music of the period. He became a French subject in 1661.

Armide is an opera by Jean-Baptiste Lully. The libretto by Philippe Quinault is based on Torquato Tasso's poem La Gerusalemme liberata (Jerusalem Delivered). The work is in the form of a tragédie en musique, a genre invented by Lully and Quinault.

Critics in the 18th century regarded Armide as Lully's masterpiece. It continues to be well-regarded, featuring some of the best-known music in French baroque opera and being arguably ahead of its time in its psychological interest. Unlike most of his operas, Armide concentrates on the sustained psychological development of a character — not Renaud, who spends most of the opera under Armide's spell, but Armide, who repeatedly tries without success to choose vengeance over love.

- Lully: Armide, Act 2 - Enfin, il est en ma puissance ("At last, he is in my power"; p. 752)

Lyrics translated at http://operatoriobeginners.wordpress.com/2011/08/29/french-baroque-3-translation-of-opera-text/.

‘Enfin, il est en ma puissance’ (Armida’s soliloquy from Armide, Act 2, Scene 5 [1686])

Text by Philippe Quinault; English translation by John Underwood

Armida, a dagger in her hand

At last, he is in my power,

This fatal foe, this proud victor.

Sleep’s charm delivers him to my revenge.

I’ll pierce his invincible heart.

He it was who freed my captive slaves,

Now may he feel my rage …

Armida makes to strike Rinaldo, but discovers she cannot pursue her plan of taking his life.

What feeling troubles me, what makes me hesitate?

What is it that Pity says to me on his behalf?

Come, strike! … Ye gods, what holds me back?

Now to it! … I am trembling! Take revenge … I am sighing!

Is it thus that today I am avenged?

My anger dissolves whenever I approach him.

The more I look at him, the vainer is my rage.

My trembling arm refuses me my hatred.

Ah, what cruelty it would be to take his life!

Everything gives way for this young hero.

Who would believe that he was born for war alone?

He seems to have been made only for love.

Is it only by his death that I would be avenged?

Ah, would love’s punishments not be enough?

Since he found in my eyes not charms enough,

At least by my spells I’ll make him dote [on me],

That I might hate him, if I can.

Come, confirm my desires,

Demons, assume the shapes of sweet breezes.

I yield to this victor, I am won by pity;

Come hide my weakness and shame

In far distant deserts: now bend

your course, lead us to the world’s end.

The Demons, changed into Zephyrs, carry Rinaldo and Armida off.

Note: The French name forms ‘Armide’ and ‘Renaud’ are given here in their Italian equivalents, ‘Armida’ and ‘Rinaldo’. The story of the opera is taken from an epic Italian poem by Torquato Tasso, Jerusalemme liberata (completed in 1575). – Lully’s and Quinault’s version of just a part of this epic tale was immensely popular, and remained in the repertoire in Paris until 1764.

‘Enfin, il est en ma puissance’ (Armida’s soliloquy from Armide, Act 2, Scene 5 [1686])

Text by Philippe Quinault; English translation by John Underwood

Armida, a dagger in her hand

At last, he is in my power,

This fatal foe, this proud victor.

Sleep’s charm delivers him to my revenge.

I’ll pierce his invincible heart.

He it was who freed my captive slaves,

Now may he feel my rage …

Armida makes to strike Rinaldo, but discovers she cannot pursue her plan of taking his life.

What feeling troubles me, what makes me hesitate?

What is it that Pity says to me on his behalf?

Come, strike! … Ye gods, what holds me back?

Now to it! … I am trembling! Take revenge … I am sighing!

Is it thus that today I am avenged?

My anger dissolves whenever I approach him.

The more I look at him, the vainer is my rage.

My trembling arm refuses me my hatred.

Ah, what cruelty it would be to take his life!

Everything gives way for this young hero.

Who would believe that he was born for war alone?

He seems to have been made only for love.

Is it only by his death that I would be avenged?

Ah, would love’s punishments not be enough?

Since he found in my eyes not charms enough,

At least by my spells I’ll make him dote [on me],

That I might hate him, if I can.

Come, confirm my desires,

Demons, assume the shapes of sweet breezes.

I yield to this victor, I am won by pity;

Come hide my weakness and shame

In far distant deserts: now bend

your course, lead us to the world’s end.

The Demons, changed into Zephyrs, carry Rinaldo and Armida off.

Note: The French name forms ‘Armide’ and ‘Renaud’ are given here in their Italian equivalents, ‘Armida’ and ‘Rinaldo’. The story of the opera is taken from an epic Italian poem by Torquato Tasso, Jerusalemme liberata (completed in 1575). – Lully’s and Quinault’s version of just a part of this epic tale was immensely popular, and remained in the repertoire in Paris until 1764.

Jean-Baptiste Lully composed the opera Armide in the late 1600s, during the reign of Louis XIV. Read p. 752 carefully as it describes that work and this part of it. Armide (=Armida) is the female character, the main character. Armida lives in Muslim culture and is variously described as a sorceress, an enchantress, and a witch. She has been asked to thwart the efforts of the crusader knight Renaud, even murder him. She does succeed in casting a spell on him, but finds that she also has fallen in love with him, so following through with murder seems impossible. She approaches to do the deed--that is the setting for this song from the end of Act II of the opera. The story itself was based on a fictional epic poem of the 1500s.

- Elizabeth-Claude Jacquet de la Guerre: Pieces de clavecin ("Pieces for the Harpischord"; p. 753)

Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre (full name Élisabeth-Claude Jacquet de la Guerre; born Élisabeth Jacquet, 17 March 1665, Paris – 27 June 1729, Paris) was a French musician, harpsichordist and composer.

This female composer and musician had performed in the court of Louis XIV since she was age 5. This composition was for a dance. Read the description on p. 753. Note the sound of the harpischord (clavecin), precursor to the modern piano.

At the court of Louis XIV she was noticed by Madame de Montespan, and was kept on in her entourage. She later married the organist Marin de La Guerre in 1684 and left the court. Thereafter she was known as Elisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre.

After her marriage she taught and gave concerts at home and throughout Paris, and gained much acclaim. A quote from Titon du Tillet speaks of her "marvellous facility for playing preludes and fantasies off the cuff.

Sometimes she improvises one or another for a whole half hour with tunes and harmonies of great variety and in quite the best possible taste, quite charming her listeners." (Le Parnasse Français, 1732) Elisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre was one of the few well-known women composers of her time.

Recently there has been a renewal of interest in her compositions and a number have been recorded. Her first publication was her Premier Livre de Pièces de Clavessin, printed in 1687. It was one of the few collections of harpsichord pieces printed in France in the 17th-century, along with those of Chambonnières, Lebègue and d'Anglebert.

On 15 March 1694, the production of her opera Céphale et Procris at the Académie Royale de Musique was the first written by a woman in France. The next year, 1695, she composed a set of trio sonatas which, with those of Marc-Antoine Charpentier, François Couperin, Jean-Féry Rebel and Sébastien de Brossard, are among the earlist French examples of the sonata.

The next few years heralded the deaths of almost all of her near relations: her only son, mother, father, husband and brother Nicolas, and were not productive times. 1707 saw the publication of Pièces de Clavecin qui peuvent se jouer sur le Viollon, a new set of harpsichord pieces, followed by six Sonates pour le Viollon et pour le Clavecin.

These works are an early example of the new genre of accompanied harpsichord works, where the instrument is used in an obbligato role with the violin; Rameau's Pieces de Clavecin en Concerts are somewhat of the same type.

The dedication of the 1707 work speaks of the continuing admiration and patronage of Louis XIV: "Such happiness for me, Sire, if my latest work may receive as glorious a reception from Your Majesty as I have enjoyed almost from the cradle, for, Sire, if I may remind you, you never spurned my youthful offerings.

You took pleasure in seeing the birth of the talent that I have devoted to you; and you honoured me even then with your commendations, the value of which I had no understanding at the time. My slender talents have since grown. I have striven even harder, Sire, to deserve your approbation, which has always meant everything to me...." She returned to vocal composition with the publication of two books of Cantates françoises sur des sujets tirez de l'Ecriture in 1708 and 1711.

Her last publication, 15 years before her death, was a collection of secular Cantates Françoises (c. 1715). In the inventory of her possessions after her death, there were three harpsichords: a small instrument with white and black keys, one with black keys, and a large double manual Flemish harpsichord.

Embedding disabled by request

https://youtu.be/wHCKCMUqCEU

- Henry Purcell: Dido and Aeneas, Dido’s Lament (p. 75) Henry Purcell (/ˈpɜːrsəl/;[1] c. 10 September 1659[Note 1] – 21 November 1695) was an English composer. Although incorporating Italian and French stylistic elements into his compositions, Purcell's legacy was a uniquely English form of Baroque music. He is generally considered to be one of the greatest English composers; no other native-born English composer approached his fame until Edward Elgar. Dido and Aeneas (Z. 626)[1] is an opera in a prologue and three acts, written by the English Baroque composer Henry Purcell with a libretto by Nahum Tate. The dates of the composition and first performance of the opera are uncertain. It was composed no later than July 1688,[2] and had been performed at Josias Priest's girls' school in London by the end of 1689.[3] Some scholars argue for a date of composition as early at 1684.[4][5] The story is based on Book IV of Virgil's Aeneid.[6] It recounts the love of Dido, Queen of Carthage, for the Trojan hero Aeneas, and her despair when he abandons her. A monumental work in Baroque opera, Dido and Aeneas is remembered as one of Purcell's foremost theatrical works.[6] It was also Purcell's first opera, as well as his only all-sung dramatic work. One of the earliest English operas, it owes much to John Blow's Venus and Adonis, both in structure and in overall effect.[6] The influence of Cavalli's opera Didone is also apparent.

For lyrics see: http://www.absolutelyrics.com/lyrics/view/alison_moyet

/dido's_lament,3a_when_i_am_laid_in_earth; but don't buy the ring tone.

/dido's_lament,3a_when_i_am_laid_in_earth; but don't buy the ring tone.

"Dido's Lament", by Purcell, is also called "When I am laid in earth". The story it relates to is from Book 4 of the ancient epic poem by Vergil called The Aeneid. Dido, the Queen of Carthage, and Aeneas, the warrior prince from ancient Troy, had fallen in love. But, Aeneas was determined to fulfill his duty and divine destiny and go to Italy to found a new kingdom; eventually that becomes Rome. Aeneas is pulled by duty and destiny, and as queen, Dido cannot leave with him. In anguish of his departure, she makes arrangements to put herself to death on a funeral pyre. Thus--the lament. On "Dido's Lament": This song is one ARIA in Purcell's opera called Dido and Aeneas. Read the great description of this on p. 757.

When I am laid, am laid in earth, may my wrongs create

No trouble, no trouble in, in thy breast.

When I am laid, am laid in earth, may my wrongs create

No trouble, no trouble in, in thy breast.

Remember me, remember me, but ah!

Forget my fate.

Remember me, but ah!

Forget my fate.

Remember me, remember me, but ah!

Forget my fate.

Remember me, but ah!

Forget my fate.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C3TUWU_yg4s Henry Purcell - When I am laid in earth (Dido's Lament) - Dido and Aeneas - Tatiana Troyanos, 3:45

Henry Purcell - When I am laid in earth (Dido's Lament, aria) - Dido and Aeneas - Tatiana Troyanos. When I am laid, am laid in earth, May my wrongs create No trouble, no trouble in thy breast; Remember me, remember me, but ah! forget my fate. Remember me, but ah! forget my fate. See: - Dido's Lament: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dido%27s... - Henry Purcell: http://www.baroquemusic.org/bqxpurcel... - Dido and Aeneas: http://www.naxos.com/education/opera_... - Tatiana Troyanos (mezzo-soprano): http://www.allmusic.com/artist/tatian... - Origin of the story in Aeneid by Virgil: http://en.wikipedia.org

/wiki/Aeneid https://youtu.be/vK06iwXT0Jw

When I am laid, am laid in earth, may my wrongs create

No trouble, no trouble in, in thy breast.

When I am laid, am laid in earth, may my wrongs create

No trouble, no trouble in, in thy breast.

Remember me, remember me, but ah!

Forget my fate.

Remember me, but ah!

Forget my fate.

Remember me, remember me, but ah!

Forget my fate.

Remember me, but ah!

Forget my fate.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C3TUWU_yg4s Henry Purcell - When I am laid in earth (Dido's Lament) - Dido and Aeneas - Tatiana Troyanos, 3:45

Henry Purcell - When I am laid in earth (Dido's Lament, aria) - Dido and Aeneas - Tatiana Troyanos. When I am laid, am laid in earth, May my wrongs create No trouble, no trouble in thy breast; Remember me, remember me, but ah! forget my fate. Remember me, but ah! forget my fate. See: - Dido's Lament: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dido%27s... - Henry Purcell: http://www.baroquemusic.org/bqxpurcel... - Dido and Aeneas: http://www.naxos.com/education/opera_... - Tatiana Troyanos (mezzo-soprano): http://www.allmusic.com/artist/tatian... - Origin of the story in Aeneid by Virgil: http://en.wikipedia.org

/wiki/Aeneid https://youtu.be/vK06iwXT0Jw

- Handel: Messiah, Hallelujah Chorus (p. 790)

This famous chorus is part of the renowned ORATORIO called Messiah. Read p. 790 carefully for the description of the term "oratorio" and note how it differs from opera. Then read that page for its description of this work in particular. Handel took the common Christian approach and understanding of scriptures as predicting and praising Jesus as the Christ, the Messiah. Most of the lyrics are taken from scriptural passages, especially those found in the Biblical books of Isaiah, Luke, and Revelation.

Messiah (HWV 56)[1] is an English-language oratorio composed in 1741 by George Frideric Handel, with a scriptural text compiled by Charles Jennens from the King James Bible, and from the version of the Psalms included with the Book of Common Prayer. It was first performed in Dublin on 13 April 1742 and received its London premiere nearly a year later. After an initially modest public reception, the oratorio gained in popularity, eventually becoming one of the best-known and most frequently performed choral works in Western music.[n 1]

Handel's reputation in England, where he had lived since 1712, had been established through his compositions of Italian opera. He turned to English oratorio in the 1730s in response to changes in public taste; Messiah was his sixth work in this genre. Although its structure resembles that of opera, it is not in dramatic form; there are no impersonations of characters and no direct speech. Instead, Jennens's text is an extended reflection on Jesus Christ as Messiah. The text begins in Part I with prophecies by Isaiah and others, and moves to the annunciation to the shepherds, the only "scene" taken from the Gospels. In Part II, Handel concentrates on the Passion and ends with the "Hallelujah" chorus. In Part III he covers the resurrection of the dead and Christ's glorification in heaven.

Handel wrote Messiah for modest vocal and instrumental forces, with optional settings for many of the individual numbers. In the years after his death, the work was adapted for performance on a much larger scale, with giant orchestras and choirs. In other efforts to update it, its orchestration was revised and amplified by (among others) Mozart. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries the trend has been towards reproducing a greater fidelity to Handel's original intentions, although "big Messiah" productions continue to be mounted. A near-complete version was issued on 78 rpm discs in 1928; since then the work has been recorded many times.

EMI have just released a DVD of King's College Choir performing Handel's Messiah. You can buy both the DVD and CD from the The Shop at King's, King's Parade, Cambridge or online from the Friends of King's website - www.kingsfriends.org or on the EMI website: www.emiclassics.com/dvds.php The Messiah DVD captures an extraordinary performance in the magnificent setting of the College Chapel. The performance was recorded during this year's Easter at Kings festival and was screened in over 85 cinemas across Europe and North America. It was the first time a choral concert had been broadcast live throughout cinemas. The critically-acclaimed concert features the Academy of Ancient Music conducted by Stephen Cleobury together with with soloists Ailish Tynan, Alice Coote, Allan Clayton and Matthew Rose, and the King's College Choir. The concert commemorated both the 250th anniversary of the death of George Frideric Handel and the 800th anniversary of the University of Cambridge.

https://youtu.be/C3TUWU_yg4s

The Arts and Royalty

- Chapter 23 (pp. 742-755); Rubens; Poussin; Moliere; royalty using the arts; review the Week 2 “Music Folder”

- Rubens and Poussin at http://www.visitmuseums.com/exhibition/from-baroque-to-classicism-rubens-poussin-and-17th-85 and http://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/bio/p/poussin/biograph.html

Rubens and Poussin

The grand master of baroque, Pierre-Paul Rubens arrived in Paris in 1625 with his series of canvases depicting the life of Mary of Medicis, Queen of France and widow of Henri IV. Commissioned four years before by the Queen, this imposing series of 24 pieces was destined to decorate the west wing of the Luxembourg palace in Paris. Today it hangs in the Louvre.

At the start of the 17th century, 70% of production from Antwerp was exported, a major portion of which to France. In Paris, Saint-Germain des Prés village fair, hosted by Nordic merchants, sold a great many Flemish works of art.

Under the reign of Henri IV, then the regency of Mary of Medicis, Flemish painters with Pierre-Paul Rubens foremost among them, obtained the lion’s share of royal commissions, including Philippe de Champaigne for portraits or Frans Snyders for animal art.

This strong presence in France motivated French artists, such as the Le Nain brothers, to adopt Flemish subjects and models.

The 17th century was therefore one where artistic currents changed, when the French classic school influenced the Europe of Arts, supported by the extensive political power of Louis XIV’s reign.

Poussin

French painter, a leader of pictorial classicism in the Baroque period. Except for two years as court painter to Louis XIII, he spent his entire career in Rome. His paintings of scenes from the Bible and from Greco-Roman antiquity influenced generations of French painters, including Jacques-Louis David, J.-A.-D. Ingres, and Paul Cézanne.

Childhood and early travels

Poussin was born in a small hamlet on the Seine River, the son of small farmers. He was educated at the nearby town of Les Andelys, and he apparently did not show any interest in the arts until the painter Quentin Varin visited the village in 1612 to produce several paintings for the Church of Le Grand Andely. Poussin's interest in the arts was awakened, and he decided to become a painter. As this was impossible in Les Andelys, he left his home, going first to Rouen and then to Paris to find a suitable teacher. His poverty and ignorance made this search very difficult. He found no satisfactory master and studied at different times under several minor painters. During this period Poussin endured great hardships and had to return to his paternal home, where he arrived ill and humiliated.

Recovering after a year, Poussin again set out for Paris, not only to continue his studies but also to pursue another aim. While previously in Paris, he had been exposed to the art of the Italian High Renaissance through reproductions of Raphael's paintings. These engravings, according to his biographer Giovanni Battista Passeri, inspired him to go to Rome, which was then the centre of the European art world. But only in 1624 was Poussin successful in reaching Rome, with the help of Giambattista Marino, the Italian court poet to Marie de Médicis.

First Roman period

Marino commissioned Poussin to make a series of mythological drawings illustrating Ovid's Metamorphoses. Poussin meanwhile experimented with various painting styles then current in Rome, an important influence being that of the Bolognese painter Domenichino. Poussin's culminating work of this period was a large altarpiece for St. Peter's representing the Martyrdom of St. Erasmus (1629). But it was a comparative failure with the artistic community in Rome, and Poussin never again tried to compete with the Italian masters of the Baroque style on their own ground. Thereafter he would paint only for private patrons and would confine his work to formats rarely larger than five feet in length.

Between Poussin's arrival in Rome in 1624 and his departure for France in 1640 he came to know many of Rome's most influential people, among them Cassiano dal Pozzo, secretary to Cardinal Barberini, whose rich collection of ancient Roman artifacts had a decisive influence upon Poussin's art. Through Pozzo, who became Poussin's patron, the French painter became a fervent admirer of ancient Roman civilization. From about 1629 to 1633 Poussin took his themes from classical mythology and from Torquato Tasso, and his painterly style became more romantic and poetic under the influence of such Venetian masters as Titian. Such examples of his work at this time as The Arcadian Shepherds and Rinaldo and Armida have sensuous, glowing colours and manage to communicate a true feeling for pagan antiquity.

In the mid-1630s Poussin began deliberately to turn toward Raphael and Roman antiquity for his inspiration and to evolve the purely classical idiom that he was to retain for the rest of his life. He also began painting religious themes once more. He began with stories that offered a good pageant, such as The Worship of the Golden Calf and The Rape of the Sabine Women. He went on to choose incidents of deeper moral significance in which human reactions to a given situation constitute the main interest. The most important works that exemplify this phase are those in the series of Seven Sacraments painted in 1634-42 for Pozzo. While other artists painted in the style of the Roman Baroque, Poussin tried in these works to fashion a style marked by classical clarity and monumentality. This style was inspired by Roman pre-Christian architecture and Latin books on moral conduct, as well as by the nobility and greatness of Raphael's works, which, as he believed, had renewed the spirit of antiquity.

Painter to Louis XIII

Between 1638 and 1639 Poussin's achievements in Rome attracted the attention of the French court. Louis XIII's powerful minister Cardinal Richelieu tried to persuade Poussin to return to France. Eventually Poussin reluctantly acceded to this request, journeying to Paris in 1640. Though received with great honours, Poussin nevertheless soon found himself in trouble with the ministers of the king as well as with the French artists, whom he met with the utmost arrogance. He was offered commissions for kinds of work he was not used to nor really qualified to execute, including altarpieces and the decoration of the Grande Galérie of the Louvre palace. What he produced did not elicit the praise he expected, so he left Paris in defeat in 1642 and returned to Rome. Unfortunately he did not live to see his own style of painting accepted and eventually glorified by the French Academy in the late 17th century.

Second Roman period

Many of Poussin's paintings on religious and ancient Roman subjects done in the 1640s and '50s are concerned with moments of crisis or difficult moral choice, and his heroes are those who reject vice and the pleasures of the senses in favour of virtue and the dictates of reason - e.g., Coriolanus, Scipio, Phocion, and Diogenes. Poussin's painterly style was consciously calculated to express such a mood of austere rectitude: such solemn religious works as Holy Family on the Steps (1648) exhibit only a few figures, painted in harsh colours against the severest possible background. In the landscapes Poussin began painting at this time, such as Landscape with the Body of Phocion Carried out of Athens and Landscape with Polyphemus, the disorder of nature is reduced to the order of geometry, and the forms of trees and shrubs are made to approach the condition of architecture. The composition in these paintings is worked out very carefully and has an unusual clarity of structure.

Poussin's health declined from 1660 onward, and early in 1665 he ceased to paint. He died that year and was buried in San Lorenzo in Lucina, his Roman parish church.

Assessment

Poussin believed in reason as the guiding principle of art, yet his figures are never merely cold or lifeless. They may resemble figures used by Raphael or ancient Roman sculptures in their poses, but they retain a strange and unmistakable vitality of their own. Even in Poussin's late period, when all movement, including gesture and facial expression, had been reduced to a minimum, his forms harmoniously combine vitality with intellectual order.

Philosophers Debate Politics

- Chapter 24 (pp. 776-7; 803-805)

- Hobbes: text at http://oregonstate.edu/instruct/phl201/modules/Philosophers/Hobbes/hobbes_human_nature.html; summary at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hobbes-moral/; also http://jim.com/hobbes.htm

- Locke: text at http://www.thenagain.info/Classes/Sources/Locke-2ndTreatise.html; General background of the concept at http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/teachers/lesson_plans/pdfs/unit1_12.pdf

"The Arts and Royalty; Philosophers Debate Politics" Please respond to one (1) of the following, using sources under the Explore heading as the basis of your response:

- In this week’s readings, a dispute in the French royal court is described about whether Poussin or Rubens was the better painter. Take a painting by each, either from our book or a Website below, and compare them and explain which you prefer. There is another conflict between the playwright Moliere and a well-born Parisian; Louis XIV stepped in. Explain how Louis XIV used the various arts and his motives for doing so. Identify one (1) example of a modern political leader approaching the arts this way.

- The philosophers Thomas Hobbes and John Locke disagreed on the understanding of political authority, with Locke taking what is commonly called the “liberal” view. Choose a side (be brave perhaps; take a side you actually disagree with). Using the writings of each given in our class text or at the Websites below, make your case for the side you chose and against the other side. Identify one (1) modern situation in the world where these issues are significant.

REVIEW

Revolution and Enlightenment, 1550–1800

The Scientific Revolution gave rise to a intellectual movement—the Enlightenment. Enlightenment thought provided the philosophical foundations for the American Revolution. Britain lost its colonies in North America to the newly formed United States, while Spain and Portugal held onto their profitable Latin American colonies.

The Scientific Revolution

* How did new discoveries in astronomy change the way people viewed the universe?

* What is the new scientific method and what impact did it have?

* What contributions did Newton and other scientists make to the Scientific Revolution?

The Enlightenment

The Impact of the Enlightenment

Colonial Empires and the American Revolution

Lecture

The Scientific Revolution

In What Went Wrong?, Bernard Lewis writes of the key role of the Middle East in the rise of science in the Middle Ages, before things went wrong: And then, approximately from the end of the Middle Ages, there was a dramatic change. In Europe, the scientific movement advanced enormously in the era of the Renaissance, the Discoveries, the technological revolution, and the vast changes, both intellectual and material, that preceded, accompanied, and followed them. In the Muslim world, independent inquiry virtually came to an end, and science was for the most part reduced to the veneration of a corpus of approved knowledge. There were some practical innovations — thus, for example, incubators were invented in Egypt, vaccination against smallpox in Turkey. These were, however, not seen as belonging to the realm of science, but as practical devices, and we know of them primarily from Western travelers.

Another example of the widening gap may be seen in the fate of the great observatory built in Galata, in Istanbul, in 1577. This was due to the initiative of Taqi al-Din (ca. 1526-1585), a major figure in Muslim scientific history and the author of several books on astronomy, optics, and mechanical clocks. Born in Syria or Egypt (the sources differ), he studied in Cairo, and after a career as jurist and theologian he went to Istanbul, where in 1571 he was appointed munejjim-bash, astronomer (and astrologer) in chief to the Sultan Selim II. A few years later her persuaded the Sultan Murad III to allow him to build an observatory, comparable in its technical equipment and its specialist personnel with that of his celebrated contemporary, the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe. But there the comparison ends. Tycho Brahe's observatory and the work accomplished in it opened the way to a vast new development of astronomical science. Taqi al-Din's observatory was razed to the ground by a squad of Janissaries, by order of the sultan, on the recommendation of Chief Mufti. This observatory had many predecessors in the lands of Islam; it had no successors until the age of modernization.

The relationship between Christendom and Islam in the sciences was now reversed. Those who had been disciples now became teachers; those who had been masters became pupils, often reluctant and resentful pupils. They were willing enough to accept the products of infidel science in warfare and medicine, where they could make the difference between victory and defeat, between life and death. But the underlying philosophy and the sociopolitical context of these scientific achievements proved more difficult to accept or even recognize.

Chapter 23: The Baroque Court -- Europe: the Americas

The Weekly videos are helpful here.

The English Enlightenment, 2:17

The Sun King, 2:50

Patronage, 2:20

Click the image below to learn more about Louis XIV and Versailles, Royal Court Patronage, and the English Enlightenment.

--------------------------------------

What is the canzona's dominant rhythm? | |||||

| |||||

Question 2: Multiple Choice

-

What is a defining characteristic of Baroque art?

What is a defining characteristic of Baroque art?Given Answer:  Attention to viewers' emotional experience of a work

Attention to viewers' emotional experience of a workCorrect Answer:  Attention to viewers' emotional experience of a work

Attention to viewers' emotional experience of a work

Question 3: Multiple Choice

-

What is the meaning of the Portuguese term barroco, from which "Baroque" likely derived?

What is the meaning of the Portuguese term barroco, from which "Baroque" likely derived?Given Answer:  Misshapen pearl

Misshapen pearlCorrect Answer:  Misshapen pearl

Misshapen pearl

Question 4: Multiple Choice

-

Why is Vivaldi's The Four Seasons known as program music?

Why is Vivaldi's The Four Seasons known as program music?Given Answer:  Its purely instrumental music is connected to a story or idea

Its purely instrumental music is connected to a story or ideaCorrect Answer:  Its purely instrumental music is connected to a story or idea

Its purely instrumental music is connected to a story or idea

Question 5: Multiple Choice

-

What Greek myth inspired Monteverdi's first opera?

What Greek myth inspired Monteverdi's first opera?Given Answer:  Orpheus and Eurydice

Orpheus and EurydiceCorrect Answer:  Orpheus and Eurydice

Orpheus and Eurydice

Question 6: Multiple Choice

-

From where did Europe receive the first load of tulip bulbs?

From where did Europe receive the first load of tulip bulbs?Given Answer:  Turkey

TurkeyCorrect Answer:  Turkey

Turkey

Question 7: Multiple Choice

-

What requirement did the Dutch state place on people in public service?

What requirement did the Dutch state place on people in public service?Given Answer:  Be a member of the Dutch Reformed Church

Be a member of the Dutch Reformed ChurchCorrect Answer:  Be a member of the Dutch Reformed Church

Be a member of the Dutch Reformed Church

Question 8: Multiple Choice

-

Of what does a vanitas painting remind the viewer?

Of what does a vanitas painting remind the viewer?Given Answer:  To focus on the spiritual, not the material

To focus on the spiritual, not the materialCorrect Answer:  To focus on the spiritual, not the material

To focus on the spiritual, not the material

Question 9: Multiple Choice

-

What distinguished Bach's cantatas from the simple melodies of the Lutheran chorales on which they were based?

What distinguished Bach's cantatas from the simple melodies of the Lutheran chorales on which they were based?Given Answer:  Addition of counterpoint

Addition of counterpointCorrect Answer:  Addition of counterpoint

Addition of counterpoint

Question 10: Multiple Choice

What might the pearls In Vermeer's Woman with a Pearl Necklace represent? | |||||

| |||||

is not like our daily lives, it is more like the scenario created in a post-apocalyptic movie, but even further removed from social convention. In that world there would be no trust or fairness. You would have desires (such as food and water) that others may also want. If they are stronger then you, they could take away whatever you have or kill you. If you were stronger or lucky, maybe you would take or kill.

is not like our daily lives, it is more like the scenario created in a post-apocalyptic movie, but even further removed from social convention. In that world there would be no trust or fairness. You would have desires (such as food and water) that others may also want. If they are stronger then you, they could take away whatever you have or kill you. If you were stronger or lucky, maybe you would take or kill.  that person or get rid of them. There is strength in numbers. But, if we can band together for mutual protection from an individual, then we can also agree upon common rules that mutually protect us from each other. That is, to make and live by a social agreement by which all of us accept limitations on our liberty in exchange for common security.

that person or get rid of them. There is strength in numbers. But, if we can band together for mutual protection from an individual, then we can also agree upon common rules that mutually protect us from each other. That is, to make and live by a social agreement by which all of us accept limitations on our liberty in exchange for common security.