The presentation may contain content that is deemed objectionable to a particular viewer because of the view expressed or the conduct depicted. The views expressed are provided for learning purposes only, and do not necessarily express the views, or opinions, of Strayer University, your professor, or those participating in videos or other media.

We will have two ten-minute breaks: at 7:30 - 7:40; and, at 9:00 pm - 9:10 pm. I will take roll after the second break before you are dismissed at 10 pm.

Chapters 21 & 22

21 Prosperity and Change in the Twenties

21-1 The Consumer Economy

1920s Work

1920s Consumerism

21-2 The End of the Progressive Era

National Politics

Prohibition

21-3 A New Culture: The Roaring Twenties

1920s Popular Culture

The “New Negro”

Changing Roles for Women

Disillusioned Writers, Liberalizing Mores

21-4 Reactions

Religious Divisions

Immigration Restriction and Quotas

Social Intolerance

The Election of 1928

22 The Great Depression and the New Deal

22-1 The Economics and Politics of Depression

Statistics

Hoover

22-2 The Depression Experience in America

Urban America

Rural America

Cultural Politics

Radicalizing Politics

The Election of 1932

22-3 The New Deal

The First New Deal

Critics of the First New Deal

The Second New Deal

Decline and Consolidation

22-4 The Effects of the New Deal

Chapter 21 Prosperity and Change in the Twenties

The 1920s (pronounced "nineteen-twenties", commonly abbreviated as the "Twenties") was a decade of the Gregorian calendar that began on January 1, 1920 and ended on December 31, 1929. In North America, it is frequently referred to as the "Roaring Twenties" or the "Jazz Age", while in Europe the period is sometimes referred to as the "Golden Age Twenties" because of the economic boom following World War I. French speakers refer to the period as the "années folles" ("Crazy Years"), emphasizing the era's social, artistic, and cultural dynamism.

The economic prosperity experienced by many countries during the 1920s (especially the United States) was similar in nature to that experienced in the 1950s and 1990s. Each period of prosperity was the result of a paradigm shift in global affairs. These shifts in the 1920s, 1950s, and 1990s, occurred as the result of the conclusion of World War I and Spanish flu, World War II, and the Cold War, respectively.

The 1920s saw foreign oil companies begin operations throughout South America. Venezuela became the world's second largest oil producing nation.

Prosperity in the 1920s was not ubiquitous, however. The German Weimar Republic experienced a severe economic downturn as a result of the enormous debts it agreed to repay as part of the Treaty of Versailles. The economic crisis that resulted led to a devaluation of the Mark in 1923 and to severe economic problems. The economic hardships experienced by Germans during this period resulted in an environment conducive to the rise of the Nazi Party.

The 1920s were also characterized by the rise of radical political movements, especially in regions that were once part of empires. Communism spread as a consequence of the October Revolution and the Bolsheviks' victory in the Russian Civil War. Fear of the spread of Communism led to the emergence of Far Right political movements and Fascism in Europe. Economic problems contributed to the emergence of dictators in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, to include Józef Piłsudski in the Second Polish Republic, and Peter and Alexander Karađorđević in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

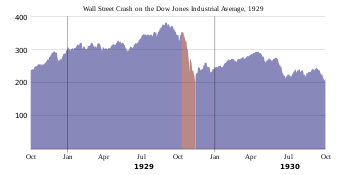

The devastating Wall Street Crash in October 1929 is generally viewed as a harbinger of the end of 1920s prosperity in North America and Europe.

From left, clockwise: Third Tipperary Brigade Flying Column No. 2 under Sean Hogan during the Irish Civil War; Prohibition agents destroying barrels of alcohol in accordance to the 18th amendment, which made alcoholic beverages illegal throughout the entire decade; In 1927, Charles Lindbergh embarks on the first solo nonstop flight from New York to Paris on the Spirit of St. Louis; A crowd gathering on Wall Street after the 1929 stock market crash, which led to the Great Depression; Benito Mussolini and Fascist Blackshirts during the March on Rome in 1922; the People's Liberation Army attacking government defensive positions in Shandong, during the Chinese Civil War; The Women's suffrage campaign leads to the ratification of the 19th amendment in the United States and numerous countries granting women the right to vote and be elected; Babe Ruth becomes the most iconic baseball player of the time.

The Roaring Twenties brought about several novel and highly visible social and cultural trends. These trends, made possible by sustained economic prosperity, were most visible in major cities like New York, Chicago, Paris, Berlin and London. "Normalcy" returned to politics in the wake of hyper-emotional patriotism during World War I, jazz blossomed, and Art Deco peaked. For women, knee-length skirts and dresses became socially acceptable, as did bobbed hair with a marcel wave. The women who pioneered these trends were frequently referred to as flappers.[4]

The era saw the large-scale adoption of automobiles, telephones, motion pictures and electricity, unprecedented industrial growth, accelerated consumer demand and aspirations, and significant changes in lifestyle and culture. The media began to focus on celebrities, especially sports heroes and movie stars. Large baseball stadiums were built in major U.S. cities, in addition to palatial cinemas. The decade also saw the advent of television, albeit on a very limited scale.[5]

In most Western countries women gained the right to vote. The 1920s also marked the start of urban migration in the United States. By the end of the decade, the population in urban areas surpassed that of the population in rural areas.

United States

- Prohibition of alcohol occurs in the United States. Prohibition in the United States began January 16, 1919, with the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S.Constitution, effective as of January 17, 1920, and it continued throughout the 1920s. Prohibition was finally repealed in 1933. Organized crime turns to smuggling and bootlegging of liquor, led by figures such as Al Capone, boss of the Chicago Outfit.

- The Immigration Act of 1924 places restrictions on immigration. National quotas curbed most Eastern and Southern European nationalities, further enforced the ban on immigration of East Asians, Indians and Africans, and put mild regulations on nationalities from the Western Hemisphere (Latin Americans).

- The major sport was baseball and the most famous player was Babe Ruth.

- The Lost Generation (which characterized disillusionment), was the name Gertrude Stein gave to American writers, poets, and artists living in Europe during the 1920s. Famous members of the Lost Generation include Cole Porter, Gerald Murphy, Patrick Henry Bruce, Waldo Peirce, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Zelda Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, John Dos Passos, and Sherwood Anderson.

- A peak in the early 1920s in the membership of the Ku Klux Klan of 4 to 5 million members (after its reemergence in 1915), followed by a rapid decline down to an estimated 30,000 members by 1930.

- The Scopes Trial (1925), which declared that John T. Scopes had violated the law by teaching evolution in schools, creating tension between the competing theories of creationism and evolutionism.

Economics

- Economic boom ended by "Black Tuesday" (October 29, 1929); the stock market crashes, leading to the Great Depression. The market actually began to drop on Thursday October 24, 1929 and the fall continued until the huge crash on Tuesday October 29, 1929.

- The New Economic Policy is created by the Bolsheviks in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

- The Dawes Plan, which lasted from 1924 to 1928.

- Average annual inflation for the decade was virtually zero but individual years ranged from a high of 3.47% in 1925 to a deflationary -11% in 1921.[8]

Summary

Roaring Twenties

Religious Divisions

Professional Sports (references to amateur as well)

The "New" Woman

Jazz swept through the nation in the 1920s, putting on display the dramatic prosperity of the era, as well as the acceptance of a new role for women and the celebration and abduction of African American cultural forms.

SMALL GROUP WORK

Political Cartoons

Age of Prosperity

http://americainclass.org/sources/becomingmodern/prosperity/text1/text1.htm

Crash

http://americainclass.org/sources/becomingmodern/prosperity/text4/text4.htm

1920s American Culture: City Life & Values

http://study.com/academy/lesson/1920s-american-culture-city-life-values.html

American Art, Pop Culture & Literature of the 1920s

http://study.com/academy/lesson/american-art-pop-culture-literature-of-the-1920s.html

21-1 The Consumer Economy

During the 1920s, the United States became the wealthiest nation in the world. It took several years for the American economy to recover from its conversion to wartime production during World War I, when goods like guns and naval ships were produced in lieu of consumer items. But by 1921, the American economy was on an upward surge. American per capita incomes grew by more than 30 percent during the decade, industrial output increased by 60 percent, and unemployment in most parts of the country stayed below 5 percent. Immense corporations dominated the economy, making their mark on national culture. And most people enjoyed rising wages and rising standards of living. In 1929, five out of every six privately owned cars in the world belonged to Americans.

1920s Consumerism, 3:38

https://youtu.be/NvtsYZjL-wI

1920s Work

Working at Ford in the 1920s - Part One, 4:22

In the 1920s, Ford Motor Co. was considered the leader in manufacturing technology and practices. Elements of Taylor's scientific management were combined with what economists now call "efficiency wages" (wages well above the general market - the famous $5 day). In this video, workers and others of that era reflect on working at Ford. Some are positive; others not. This is Part One.

https://youtu.be/QtYRLtT8bvY

Good Times

The economy was healthy for several reasons. For one, the industrial production of Europe had been destroyed by the war, making American goods the dominant products available in Europe. New techniques of production and pay were another significant factor in the booming American economy. Henry Ford was a leader in developing both. First, he revolutionized the automobile industry with his development of the assembly line, a mechanized belt that moved a car chassis down a line where each man performed a single small task, over and over again. Although this innovation dramatically sped up production, it alienated workers from the final product they were making because they worked on only one small aspect of a larger product. Ford had a wonderful solution to this problem: he realized that, in order to keep selling cars by the thousands, he would have to pay his workers enough for them to become customers too. His 1914 innovation, the five-dollar day (when a salary of $1.50 per day was standard), shocked other businessmen at first, but by the 1920s, other business owners were coming to understand that they could mass-produce consumer goods only if they also created a supply of consumers. In the 1920s, the economy began to transition from being driven by large industries (such as railroads and steel) to being driven by consumer dollars.

The American Economy Boom of the 1920s, 4:14

https://youtu.be/PdDuiZwmAfo

Welfare Capitalism

Along with recognizing the need to pay higher wages, many manufacturers began to think of their factories not just as places of work but also as social settings, where men and women spent a large part of their waking hours. A handful of pioneers in welfare capitalism, such as the Heinz Company (producer of soup, ketchup, and baked beans), reasoned that happy workers would be more productive than resentful ones. Heinz and other companies improved lighting and ventilation and also provided company health plans, recreation centers, and even psychologists to tend to their employees. Many companies shortened the workweek. And in some firms, company unions replaced the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in representing workers' grievances to management.

1920s Consumerism

Despite these obstacles, ordinary working-class people enthusiastically entered the consumer society of the 1920s, buying a wide assortment of laborsaving devices. Speeding this process, domestic electrification spread rapidly throughout the United States, giving most urban families electric lighting and power for the first time. People could now aspire to own new inventions like cars, refrigerators, toasters, radios, telephones, washing machines, vacuums, and phonographs, as well as nationally marketed foods, clothes, and cosmetics.

Advertisements

These new consumer products spawned advertisements, which were everywhere in the 1920s: on the radio and on billboards, in magazines and newspapers, even painted on rocks and trees. With nationwide marketing came nationwide advertising campaigns by giant companies like Kellogg's, Gillette, Palmolive, and Nabisco. Most of the money that consumers paid when they bought goods like toothpaste was used to pay for advertising rather than for the actual product. Supermarkets were another 1920s invention, replacing the old over-the-counter stores. Now the customer, instead of asking a clerk for items one by one, chose items from open shelves, put them into a basket, and paid for them all at once.

Albert Lasker, Alfred Sloan, and Bruce Barton were all pioneers of the field of marketing and advertising, heightening the American public's interest in orange juice (through a 1910s advertising campaign to increase consumption of oranges), tampons (by going into schools to explain to schoolgirls the process of menstruation—and how to manage it by using tampons), and baked goods (by inventing the maternal icon Betty Crocker). Bruce Barton's noteworthy 1925 book, The Man Nobody Knows, depicted Jesus Christ as the world's most successful businessman, who formulated a resonating message (as revealed in the New Testament) and an institutional infrastructure (the Apostles) to spread the Gospel. According to Barton, Jesus was the businessman all Americans should emulate.

0:02 / 0:06 History Brief: Mass Production and Advertising in the 1920s, 4:36

For teaching resources covering this material, check out our 1920s workbook: http://www.amazon.com/Roaring-Twentie... In this video, the impact of mass production, buying on credit, and advertising in the 1920s are discussed.

https://youtu.be/KJeN6RSqbOc

21-2 The End of the Progressive Era

National Politics

These perilous but generally good economic times had an effect on politics. After the unprecedented challenges of the Progressive era, when politicians sought to rein in the most egregious effects of the Industrial Revolution, the 1920s saw the rise of a dominant Republican Party that embraced a “business-first” philosophy. These Republicans presided over national politics throughout the decade, holding the presidency from 1920 until 1933.

1920's USA Boom: Explained, 4:08

This video provides an explanation of the 1920's economic boom in the United States.

https://youtu.be/O7nlvOszNVU

Red Scare

Before the economic “good times” took hold, however, America confronted a Red Scare, or fear that the United States was vulnerable to a communist takeover. Why a Red Scare? In 1917, Vladimir Lenin and his Russian Bolshevik Party (who were called the “Reds” during the Russian Civil War) seized power in Russia, declaring the advent of world communism and the end of all private property. According to the plan spelled out by Karl Marx, Lenin believed that his communist revolution would spread to all the major industrial nations, and he called for workers' uprisings everywhere. This development prompted a number of American politicians and businessmen to fear for the safety of the American capitalist system.

On top of this, the pieces of a revolutionary puzzle seemed to be moving into place in the United States. American socialism had been growing with the labor movement. The Socialist Party presidential candidate, Eugene V. Debs, won almost 1 million votes in the election of 1920—from his prison cell. He had been jailed for making speeches against U.S. participation in World War I, which he denounced as a capitalist endeavor. Many towns elected socialist mayors and council members, especially in the industrialized Northeast and along the northern stretches of the Mississippi River. And during World War I a variety of anarchists had bombed courthouses, police stations, churches, and even people's homes.

Sacco and Vanzetti

Italian immigrant suspects in a 1920 payroll heist, who were arrested, tried, and convicted of robbery and murder despite a flimsy trail of evidence

The Red Scare & Sacco and Vanzetti, 3:22

Dr. Byrd teaches about the fear of Communism that swept the U.S. during the 1920s.

https://youtu.be/8vU0LdSYB84

Prohibition

There was, however, one volatile issue that came to the forefront of American politics in the 1920s: Prohibition, or the outlawing of alcohol. After extensive political lobbying extending back before the Civil War, and empowered by the anti-German sentiment of the First World War (Germans being known for their extensive brewing tradition), Prohibition became the law of the land in 1919. The Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution prohibited the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors” in the United States.

Prohibition in the United States: National Ban of Alcohol, 4:22

https://youtu.be/_CE4u6jI_rc

21-3 A New Culture: The Roaring Twenties

With the economy seemingly good, radical politics largely on the run, and national politics not terribly interesting, many Americans turned to a vast array of leisure activities. New technology, including movie-making equipment, phonographic records, and expanded commercial radio, enhanced a vibrant social atmosphere, especially in the nation's cities. The “Roaring Twenties,” as they were sometimes called, witnessed a dramatic expansion of popular culture. However, this interest in lighter fare led some to political and intellectual disillusionment, based on the sense that Americans were leaving behind the ideals of the Progressive era in favor of less socially engaged interests. Others were more interested in using culture to break stifling bonds of long-standing restrictions. African Americans, women, and leftist intellectuals were some of the groups pushing against the old social limitations.

It was...The Roaring Twenties (includes VIDEO & PIX), 5:31

Watch this short video of the Roaring 1920's! You will be amazed at what you see and the things you didn't know about...The Roaring Twenties!

https://youtu.be/Xmqc_wJN4_M

1920s Popular Culture

In the 1920s breakthroughs in several media allowed the public to enjoy new diversions.

“Go to a motion picture … and let yourself go…. Out of the cage of everyday existence! If only for an afternoon or an evening—escape!”

—Saturday Evening Post, 1923

0:02 / 4:05 Pop Culture in the 1920's

https://youtu.be/J70eUyzC-S8

Movies

Thomas Edison and other inventors had developed moving films at the turn of the century. After a slow couple of years, films caught on in the 1910s, and by 1920 a film industry had developed in Hollywood, California, where there was plenty of open space, three hundred sunny days a year for outdoor filming, and 3,000 miles between it and Edison's patents. Far away in California, ignoring the patents, which had made most of the top-quality moviemaking equipment very expensive, was relatively easy.

Hollywood Glamour - 1920's Fashion Movie, 5:24

Hollywood Fashion and beauty from the 1920's ! A women's fashion film featuring prominent actresses of the silent movie period, modeling the latest trends in 1920's fashion. This film shows some beautiful vintage women's clothing,hairstyles and hats. Full Murray Glass film from - http://emgee.freeyellow.com/

https://youtu.be/nj1zjakXvQY

Music

Along with the movies, jazz music came into vogue during the 1920s. Originally derived as part of African American culture, jazz followed ragtime music by “crossing over” to white audiences during the 1920s. Most jazz stars of the 1920s were black men such as pianist Duke Ellington and trumpeter Louis Armstrong, some of the first African Americans to have enthusiastic white fans. Before the 1920s, Americans who wanted to listen to jazz (or any other kind of music) had had to create their own sounds or attend a concert. The invention of the phonograph, pioneered by Edison in the 1870s and popularized in the first years of the 1900s, birthed the record industry. This enabled fans to listen to their favorite artists on their gramophones as many times as they wanted.

The Jazz Age of the 1920's, 3:10

https://youtu.be/48jUyAK_4Uo

Professional Sports

Radio promoted an interest in professional and college sports in the 1920s, especially baseball, boxing, and college football. Listeners could get real-time play-byplay, hearing the actions of their favorite local team or boxer. The increased popularity of sports during the 1920s made celebrities out of the best players, the biggest of whom was the New York Yankees' slugger Babe Ruth. It was during the 1920s that baseball truly became “America's pastime,” and the 1927 New York Yankees are still considered by many to be the best baseball team of all time.

Sports in the 1920's, 2:24

Summary of Sports in the 1920s

A succinct look into sports during the 1920s, featuring Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey, Harold Grange, and Charles Lindbergh. Authors: Caleb Woolley, Connor Bolte, Joshua Lay, and Corrigan Burks

https://youtu.be/yRUzrfTOjRk

21-3b The "New Negro"

African American jazz musicians blossomed as the musical facet of a larger ferment among African Americans in the 1920s, known collectively as the Harlem Renaissance. Following the First World War and the race riots that followed, many African Americans had grown frustrated with America's entrenched racism and became motivated to challenge the prevailing order. They sought to establish themselves as different from their parents' generation, which they saw as unnecessarily kowtowing to white interests in an effort to advance through accommodation. Instead, the younger generation of African Americans declared it would rather “die fighting” than be further subjugated in American society. This new generation epitomized what one Harlem Renaissance leader, the philosopher Alain Locke, called “the new Negro.”

Despite its seemingly political goals, the Harlem Renaissance was mostly a literary celebration, as prominent authors like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston emerged under its auspices. As African Americans moved north to escape sharecropping and the social segregation of the South, many headed to the large northern cities. No neighborhood grew more than Harlem, which was by real estate code the only large neighborhood in New York City where black people could live as a group.

Several intellectuals, such as W. E. B. Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson, sought to politicize the growing number of urban black people, although few leaders had much luck organizing politically. The NAACP, meanwhile, pursued a legal strategy to end forced segregation in America's cities. Throughout much of the twentieth century, the NAACP brought these challenges to America's courts, forcing the court system to evaluate the segregation that persisted in the United States. Whether the courts were willing to confront and overturn segregation was another matter altogether.

Black History in America The Harlem Renaissance, 5:30

The Harlem Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned the 1920s. At the time, it was known as the "New Negro Movement", named after the 1925 anthology by Alain Locke. The Movement also included the new African-American cultural expressions across the urban areas in the Northeast and Midwest United States affected by the Great Migration (African American), of which Harlem was the largest. Though it was centered in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City, in addition, many francophone black writers from African and Caribbean colonies who lived in Paris were also influenced by the Harlem Renaissance.

https://youtu.be/ltJqqartR2U

Marcus Garvey

The Harlem Renaissance was not a political movement, though, and the legal strategies of the NAACP were unlikely to provoke a social movement. Marcus Garvey occupied this vacuum. The first black nationalist leader to foment a broad movement in the United States, Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association in 1914 and moved its headquarters to Harlem in 1916. Through parades, brightly colored uniforms, and a flamboyant style of leadership, Garvey advocated a celebration of blackness, the creation of black-owned and -operated businesses, and the dream of a return of all black people to Africa. Indeed, he created his own line of steamships, the “Black Star Line,” with the intention of tying together black-owned businesses in Africa, the Caribbean, and the United States. His organization won over more than 1 million members worldwide, although most mainstream American politicians ignored him. More damningly, the antipathy he suffered from other African American civil rights workers curtailed his power further. He suffered a harsh decline in the early 1920s, indicted for mail fraud while selling stock in the Black Star Line, and, in 1927, he was deported back to Jamaica, his birthplace.

Marcus Mosiah Garvey, 4:02

Born in Jamaica, Marcus Garvey (1887-1940) became a leader in the black nationalist movement by applying the economic ideas of Pan-Africanists to the immense resources available in urban centers. After arriving in New York in 1916, he founded the Negro World newspaper, an international shipping company called Black Star Line and the Negro Factories Corporation. During the 1920s, his Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) was the largest secular organization in African-American history. Indicted for mail fraud by the U.S. Justice Department in 1923, he spent two years in prison before being deported to Jamaica, and later died in London.

https://youtu.be/MVuisWJJFD8

21-3c Changing Roles for Women

Women won the right to vote with the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, one of the final great reforms of the Progressive era. The first election in which they voted put Harding into office. Many people expected the amendment to have dramatic consequences in national politics, but the female vote was actually split evenly between the candidates. Rather than swaying the balance in any one direction, unmarried women generally voted the same as their fathers, and married women generally voted the same as their husbands.

Changing Role of Women in the 1920s, 4:06

https://youtu.be/6STbnT32V2k

21-3d Disillusioned Writers, Liberalizing Mores

The 1920s also saw the coming of age of American literature. An influential group of writers, including poets T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound and novelists John Dos Passos, Ernest Hemingway, and Gertrude Stein, found commercial America vulgar—so distasteful that they declined to participate altogether. They went to Europe, usually to London and Paris, where they formed intellectual expatriate communities. But in their self-exile they remained preoccupied by their American roots and wrote some of the most effective American literature of their age. Together, the writers of the 1920s are referred to as “the Lost Generation,” mainly because of their disillusionment with the Progressive ideals that had been exposed as fraudulent during the First World War.

The Lost Generation Writers (Story Time with Mr. Beat), 3:39

Here's the story of the writers, poets, and artists who came of age during World War One, commonly referred to as The Lost Generation. Music by Electric Needle Room. Produced by Matt Beat. All images found in the public domain.

Subscribe to the Story Time with Mr. Beat podcast! https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/s...

Once upon a time there was city, named Paris, France. During the 1920s, lots of Americans moved there to escape institutionalized racism and the associated race riots, xenophobia, censorship, materialism, and Prohibition. Perhaps most importantly, they escaped there because they could get a lot more stuff for their money due to a strong American dollar compared to a weaker French franc.

Many of these American expatriates, or people living outside their home country, were writers and artists. They felt like they had more artistic freedom there than the United States. Perhaps the most famous of this group was a writer named Ernest Hemingway. He wrote a book called The Sun Also Rises. Published in 1926, the book is about a group of American expatriates who travel from Paris to watch the running of the bulls in Pamplona, Spain, among other things. At the beginning of the book, Hemingway quoted his friend and fellow writer Gertrude Stein, who called him and his friends “The Lost Generation.” Stein herself apparently heard the term from someone else, but regardless, from this point forward the writers who came of age during World War One widely became known as The Lost Generation.

All of these writers were American. While Hemingway, Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and T.S. Eliot were among the most famous associated with this group, other authors and artists that get lumped in include James Joyce, Sherwood Anderson, John Dos Passos, John Steinbeck, William Faulkner, Aldous Huxley, Isadora Duncan, and Alan Seeger. Even composers like Aaron Copland get associated with the group.

The Lost Generation writers often wrote about exaggerated experiences from their own lives. Generally these experiences revolved around World War One and the years following it. They used common themes in their writing such as the pointing out the ridiculously frivolous and materialistic lifestyles of the very rich, the breakdown of traditional gender roles, or the death of the American dream. Perhaps no novel better demonstrates all of the themes than the classic novel, The Great Gatsby, written by F. Scott Fitzgerald and published in 1925.

Why were they called a lost generation? Perhaps it was the general lack of purpose or ambition caused by having our their hopes and dreams crushed by the war. Having seen pointless death and destruction on a wide scale, many of them had lost faith in the more traditional way of life. Because of this, some became careless with their actions, not setting goals or working toward something great.

Eventually, the term Lost Generation referred to ALL Americans who came of age experiencing The Great War. Basically, we’re talking Americans born between 1883ish and 1900ish. It’s through the art, though, we feel like we really get to know who this generation was and what they truly felt while going through such a stressful and anxious time.

https://youtu.be/GHgdb3_JHrs

21-4 Reactions

With all these changes swirling around, many Americans felt uncomfortable with what they saw as the liberal mores of the youth culture and the diminishing of community life prompted by the Industrial Revolution. Some of these dissenters found a home in Protestant fundamentalism. Others rejected what they viewed as an increasing acceptance of cosmopolitanism and moral relativity. If the 1920s were an age of social and intellectual liberation, they also gave birth to new forms of reaction that created a clash of values.

The 20s - Moral Questions, 4:07

https://youtu.be/NEbD5QIvW3Q

21-4a Religious Divisions

Protestants have always been denominationally divided, but in the 1920s, a split between modernists and fundamentalists became readily apparent, leading to a landmark court case.

Modernists

On the one hand, a group of Protestants calling themselves modernists consciously sought to adapt their Protestant faith to the findings of scientific theories such as evolution and evidence that called into question the literalness of the Bible, something called biblical criticism. As these twin impulses became increasingly accepted by scholars, some liberal Protestants stopped thinking of the Bible as God's infallible word. Instead, they regarded it as a collection of ancient writings, some of them historical, some prophetic, and some mythological. In the modernists' view, represented in the writings of the notable preacher Harry Emerson Fosdick, God did not literally make the world in six days, Adam and Eve weren't actual people, and there was no real flood covering the whole earth. Men like Fosdick contended that these events were mythic explanations of human origins. Jesus was as central as ever, the divine figure standing at the center of history and transforming it, but Jesus would surely encourage his people to learn modern science and comparative religion, and to focus on other studies that enriched their knowledge of God's world and spread peace and tolerance far and wide. Not to do so was to be intolerant, and this was no way to act in a pluralistic world.

modernists

Protestants who consciously sought to adapt their Protestant faith to the findings of scientific theories, such as evolution and evidence that questioned the literalness of the Bible

fundamentalists

Protestants who insisted that the Bible should be understood as God's revealed word, absolutely true down to the last detail; they asserted and upheld the main points of traditional Christian doctrine, including biblical inerrancy, the reality of miracles, and the Virgin birth

Fundamentalists

On the other hand, the group of Protestants who have come to be known as fundamentalists (after the publication in the 1910s of a series of pamphlets labeled “the Fundamentals”) insisted that the Bible should be understood as God's revealed word, absolutely true down to the last detail. In their view, the main points of traditional Christian doctrine, including biblical inerrancy, the reality of miracles, and the Virgin birth, must be asserted and upheld. Most fundamentalists were troubled by evolution, not only because it denied the literal truth of Genesis but also because it implied that humans, evolving from lower species, were the outcome of random mutations, rather than a creation of God in His own image. Traveling evangelists such as Billy Sunday, an ex-major league baseball player, and Aimee Semple McPherson denounced evolution and all other deviations from the Gospel as the Devil's work. They also attacked the ethos of the social gospel (for more on the social gospel, see Chapter 19).

Scopes Monkey Trial

In 1925, the conflict between modernists and fundamentalists came to a head in Dayton, Tennessee, in the Scopes Monkey Trial. The case revolved around a state law that prohibited the teaching of evolution in Tennessee schools. John Scopes, a young teacher, offered to deliberately break the law to test its constitutionality (in order to obtain publicity for this struggling “New South” town) with the understanding that the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) would pay the costs to defend him. The trial drew journalists from all over America and was one of the first great media circuses of the century.

Scopes Monkey Trial

Famous 1925 court case that revolved around a state law prohibiting the teaching of evolution in Tennessee schools; John Scopes, a young teacher, offered to deliberately break the law to test its constitutionality

Religion in America during the 1920s, 9:50

This lesson focuses on understanding the formation of religion in America, paying particular attention to the rise of fundementalism and pentecostalism as reactions against evolution and religious modernism. If you are a teacher, this lesson follows along with the worksheet found here: http://db.tt/K4prz7pe Please feel free to use the worksheet to your heart's content as long as you are not charging any money for it.

https://youtu.be/gSUYNU6TbL8

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)

Organization founded in 1920 that was dedicated to fighting infringements on civil liberties, including free speech

Americanization

Notion that all American immigrant groups should leave behind their old ways and melt into the Anglo-Saxon mainstream

melting pot

Concept that all the nation's people contributed their cultural traits to a single mix, creating something altogether new

cultural pluralism

Idea that each cultural group should retain its uniqueness and not be forced to change by a restrictive state or culture

Americanization, 2:29

https://youtu.be/geMjlJXlw9g

At the trial, the nation's most prominent defense lawyer, Clarence Darrow, volunteered to help Scopes. William Jennings Bryan, the three-time Democratic presidential candidate and former secretary of state, volunteered to assist the prosecution. Darrow, an agnostic, actually called Bryan as a witness for the defense and questioned him about the origins of the earth. Did not the geological evidence prove the immense age of its rocks? asked Darrow. “I'm not interested in the age of rocks but in the Rock of Ages!” countered Bryan, who believed the earth was about 6,000 years old. Scopes was convicted (the conviction was later overturned on a technicality) and fined $100, and the law against teaching evolution remained in effect. Press coverage by urbane journalists such as H. L. Mencken and Joseph Wood Krutch ridiculed the anti-evolutionists, but fundamentalism continued to dominate rural Protestantism, especially in the South and Midwest.

The Scopes Monkey Trial Explained in 5 Minutes: US History Review, 5:06

A super fast overview of this historic trial in 1925 that began to redefine how we teach science in our public school system.

https://youtu.be/woikQ-czejY

21-4b Immigration Restriction and Quotas

If modern mores were one cause of fear, another was the transformation provoked by immigration. As we have seen in chapters past, millions of immigrants entered the United States between 1880 and 1920, and in the early 1920s many congressmen and social observers articulated a fear that the “Anglo-Saxon” heritage of the United States was being “mongrelized” by “swarthy” Europeans. These Europeans (Italians, Russians, Greeks, or other people from southern and eastern Europe) would be considered white by today's standards, but they were viewed as “others” during the 1920s because they were Catholics or Jews from countries in eastern and southern Europe, and they spoke foreign languages and cooked odd-smelling foods.

1924 Immigration Act, 4:12

Social Studies Digital Storytelling Project

https://youtu.be/rV_G1dS9qrU 21-4c Social Intolerance

Perhaps unsurprisingly, along with immigration restriction a new nativism emerged in response to all the economic and social changes taking place. Immigration restriction was one arm of this nativism, and other aspects emerged as well.

The 20s - Post War Intolerance, 4:55 Sacco and Venzetti

https://youtu.be/s2yhxaC_jNw

The Resurgence of the Klan

The Ku Klux Klan, an organization formed to “redeem” the South after Reconstruction, enjoyed a revival in the 1920s after being reborn in a ceremony on Georgia's Stone Mountain in 1915. Attesting to the power of movies during this era, the Klan's resurgence was in part inspired by the positive portrayal it received in D. W. Griffith's three-hour film Birth of a Nation. This movie is often considered the most influential in American film history for its innovative techniques and sweeping dramatic arc—despite the fact that it was overtly racist and lionized the Klan. The Klan of the 1920s saw itself as the embodiment of old Protestant and southern virtues. In this new era, the Klan enlisted members in the North as well, especially in cities, thus reemerging in response to the new urban culture of the 1920s, which it blamed on immigrants. Hiram Wesley Evans, a Texas dentist, was the Klan's Imperial Wizard during these years. He declared he was pledged to defend decency and Americanism from numerous threats: race-mixing, Jews, Catholics, and the immoralities of urban sophistication.

The Klan was mainly anti-Catholic in northern and western states. For instance, Klan members won election to the legislature in Oregon and then outlawed private schools for all children ages eight to sixteen. This was meant to attack the Catholic parochial school system that had been established in response to the overt Protestantism taught in public schools in the 1800s. Oregon's Catholics fought back, eventually battling to the U.S. Supreme Court, which, in the case of Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925), upheld the Catholic Church's right to run its own school system.

This second wave of Klan activity came to a highly publicized end when one of the organization's leaders, David (D. C.) Stephenson, was convicted of the abduction, rape, and second-degree murder of a woman who ran a literacy program in Indiana. When Indiana governor Ed Jackson refused to commute his sentence in 1927, Stephenson released the names of several politicians who had been on the Klan's payroll, leading to the indictments of many politicians, including the governor, for accepting bribes. Both the Klan and several Indiana politicians were shamed in the debacle.

KKK Democrats Lynching Killing Black & White 'Radical Republicans', 7:52

The Klu Klux Klan was founded as a Democrat proxy group. Many black Americans served in the U.S. Goverment in the 1800's and beyond as part of the "Radical Republican" party. In 1912 the 'Progressive' Democrat, President Woodrow Wilson instituted racial segregation into the Federal Government. Many blacks were subsequently pushed out of the Federal Government.

More on Woodrow Wilson: Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th President of the United States and a devout Democrat. Wilson was a Presbyterian and 'intellectual elite' of 'Progressive' idea and policies, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, where he denied entrance to black Americans. Wilson was elected President as a Democrat in 1912. Early in his first term, he instituted racial segregation in the federal government. Wilson worked with a Democratic Majority Congress to pass major 'progressive' legislation that included the Federal Trade Commission, the Clayton Antitrust Act, the Federal Farm Loan Act, America's first-ever federal 'progressive' income tax in the Revenue Act of 1913 and most notably the Federal Reserve Act. It was the Federal Reserve Act that privatized much of The Federal Reserve and some say took oversight of the monetary system of The United States away from the people.

The new Democrats represent Institutionalized Racism. The strategies of Saul Alinksy and Cloward-Priven enacted through pawns like Willie Lynch have degraded and demoralized the black community.

https://youtu.be/8bEOiDjdhF4

21-4d The Election of 1928

The multitude of changes during the 1920s and the variety of reactions against them were symbolized by the candidates in the presidential election of 1928. The election pitted the Democrat Al Smith against Republican Herbert Hoover. Hoover was idealized as a nonpolitical problem solver and an advocate of big business. He represented the freewheeling Republican values of the 1920s and also epitomized America's Anglo-Saxon Protestant heritage. Smith, meanwhile, was the Democratic governor of New York and the first Catholic to be nominated for president by one of the major parties. He represented the surging tide of social change. Although no radical, he was known to be a friend of the immigrant and a supporter of civil liberties and Progressive-era social welfare.

The American Presidential Election of 1928, 3:50

Mr. Beat's band: http://electricneedleroom.net/ Mr. Beat on Twitter: https://twitter.com/beatmastermatt Help Mr. Beat spend more time making videos: https://www.patreon.com/iammrbeat The 36th episode in a very long series about the American presidential elections from 1788 to the present. I hope to have them done by Election Day 2016. In 1928, the economy is still ridiculously strong, and Herbert Hoover has all the momentum in the world.

Feeling extra dorky? Then visit here: http://www.countingthevotes.com/1928

The 36th Presidential election in American history took place on November 6, 1928, the day I turned negative 53. Calvin Coolidge had a smooth second term. The economy remained strong, and the federal government even had a huge surplus. If he wanted to run for another full term, he probably would have been easily re-elected. However, Coolidge had announced the previous summer that he had no intention of running by cutting out strips of paper with the statement, “I do not choose to run for president in 1928” on them, and handing them out to reporters at the press conference. Coolidge said after the slips of paper were handed out, “There will be nothing more from this office today,” and he walked out.

So this left the Republican nomination wide open. The leading candidates were Herbert Hoover, the Secretary of Commerce, Frank Orren Lowden, the former governor of Illinois, and Senate Majority Leader Charles Curtis, who was from my home state of Kansas. Not impressed by these choices, many Republicans tried to draft Coolidge, but Coolidge turned it down. Hoover ended up getting the nomination, with Charles Curtis as his running mate.

The Democratic Party nominated Al Smith, the governor of New York who was running for President a third time. Smith was the first Roman Catholic to be a major party’s candidate for President. The Democrats nominated Joseph Taylor Robinson, a U.S. Senator from Arkansas, as his running mate. Robinson and Smith seemed like the odd couple, but actually complimented each other well.

No third parties really stood out during this election at all, and so we had another class two-way battle. Hoover had the momentum due to the fact that things were going pretty darn well overall in the country. In fact, at Hoover’s nomination acceptance speech, he said, "We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of this land... We shall soon with the help of God be in sight of the day when poverty will be banished from this land.”

Little did Hoover know that soon those words would come back to bite him in the butt. However, things were looking pretty good for him, especially since Al Smith’s religion became a major issue during the campaign. Many Protestants feared that Smith would take orders from the Pope if he led the country. In addition to anti-Catholicism, Smith’s opposition to Prohibition and his association with the corruption of Tammany Hall likely would cost him votes.

https://youtu.be/5IPKx3eejbI

Pre-Built Course Content

The Harlem Renaissance! 2:05

https://youtu.be/JhPd1WY5cFsA brief introduction on the Harlem Renaissance.

The song is Billie Holiday- What is this thing called love?

The Harlem Renaissance was a movement that spanned the 1920s. During the time, it was known as the "New Negro Movement", named after the 1925 anthology by Alain Locke. The Movement also included the new African-American cultural expressions across the urban areas in the Northeast and Midwest United States affected by the Great Migration (African American),[1] of which Harlem was the largest. The Harlem Renaissance was considered to be a rebirth of African American arts.[2] Though it was centered in the Harlem neighborhood of the borough of Manhattan in New York City, in addition, many francophone black writers from African and Caribbean colonies who lived in Paris were also influenced by the Harlem Renaissance.[3][4][5][6]

The Harlem Renaissance is generally considered to have spanned from about 1918 until the mid-1930s. Many of its ideas lived on much longer. The zenith of this "flowering of Negro literature", as James Weldon Johnson preferred to call the Harlem Renaissance, took place between 1924 (when Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life hosted a party for black writers where many white publishers were in attendance) and 1929 (the year of the stock market crash and the beginning of the Great Depression).

Background

Until the end of the Civil War, the majority of African Americans had been enslaved and lived in the South. After the end of slavery, the emancipated African Americans, freedmen, began to strive for civic participation, political equality and economic and cultural self-determination. Soon after the end of the Civil War the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 gave rise to speeches by African-American Congressmen addressing this Bill. By 1875 sixteen blacks had been elected and served in Congress and gave numerous speeches with their newfound civil empowerment. The Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 was renounced by black Congressmen and resulted in the passage of Civil Rights Act of 1875, part of Reconstruction legislation by Republicans. By the late 1870s, Democratic whites managed to regain power in the South. From 1890 to 1908 they proceeded to pass legislation that disenfranchised most Negros and many poor whites, trapping them without representation. They established white supremacist regimes of Jim Crow segregation in the South and one-party block voting behind southern Democrats. The Democratic whites denied African Americans their exercise of civil and political rights by terrorizing black communities with lynch mobs and other forms of vigilante violence[8] as well as by instituting a convict labor system that forced many thousands of African Americans back into unpaid labor in mines, on plantations, and on public works projects such as roads and levees. Convict laborers were typically subject to brutal forms of corporal punishment, overwork, and disease from unsanitary conditions. Death rates were extraordinarily high.[9] While a small number of blacks were able to acquire land shortly after the Civil War, most were exploited as sharecroppers.[10] As life in the South became increasingly difficult, African Americans began to migrate north in great numbers.Most of the African-American literary movement arose from a generation that had lived through the gains and losses of Reconstruction after the American Civil War. Sometimes their parents or grandparents had been slaves. Their ancestors had sometimes benefited by paternal investment in cultural capital, including better-than-average education. Many in the Harlem Renaissance were part of the Great Migration out of the South into the Negro neighborhoods of the North and Midwest. African–Americans sought a better standard of living and relief from the institutionalized racism in the South. Others were people of African descent from racially stratified communities in the Caribbean who came to the United States hoping for a better life. Uniting most of them was their convergence in Harlem.

Development

Harlem became an African-American neighborhood in the early 1900s. In 1910, a large block along 135th Street and Fifth Avenue was bought by various African-American realtors and a church group. Many more African–Americans arrived during the First World War. Due to the war, the migration of laborers from Europe virtually ceased, while the war effort resulted in a massive demand for unskilled industrial labor. The Great Migration brought hundreds of thousands of African Americans to cities such as Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, and New York.

Despite the increasing popularity of Negro culture, virulent white racism, often by more recent ethnic immigrants, continued to affect African-American communities, even in the North. After the end of World War I, many African-American soldiers—who fought in segregated units such as the Harlem Hellfighters—came home to a nation whose citizens often did not respect their accomplishments. Race riots and other civil uprisings occurred throughout the US during the Red Summer of 1919, reflecting economic competition over jobs and housing in many cities, as well as tensions over social territories.

Mainstream recognition of Harlem culture

The first stage of the Harlem Renaissance started in the late 1910s. In 1917, the premiere of Three Plays for a Negro Theatre took place. These plays, written by white playwright Ridgely Torrence, featured African-American actors conveying complex human emotions and yearnings. They rejected the stereotypes of the blackface and minstrel show traditions. James Weldon Johnson in 1917 called the premieres of these plays "the most important single event in the entire history of the Negro in the American Theater".[11] Another landmark came in 1919, when the poet Claude McKay published his militant sonnet, "If We Must Die," which introduced a dramatically political dimension to the themes of African cultural inheritance and modern urban experience featured in his 1917 poems "Invocation" and "Harlem Dancer" (published under the pseudonym Eli Edwards, these were his first appearance in print in the United States after immigrating from Jamaica).[12] Although "If We Must Die" never alluded to race, African-American readers heard its note of defiance in the face of racism and the nationwide race riots and lynchings then taking place. By the end of the First World War, the fiction of James Weldon Johnson and the poetry of Claude McKay were describing the reality of contemporary African-American life in America.In 1917 Hubert Harrison, "The Father of Harlem Radicalism", founded the Liberty League and The Voice, the first organization and the first newspaper, respectively, of the "New Negro Movement". Harrison's organization and newspaper were political, but also emphasized the arts (his newspaper had "Poetry for the People" and book review sections). In 1927, in the Pittsburgh Courier, Harrison challenged the notion of the renaissance. He argued that the "Negro Literary Renaissance" notion overlooked "the stream of literary and artistic products which had flowed uninterruptedly from Negro writers from 1850 to the present", and said the so-called "renaissance" was largely a white invention.

The Harlem Renaissance grew out of the changes that had taken place in the African-American community since the abolition of slavery, as the expansion of communities in the North. These accelerated as a consequence of World War I and the great social and cultural changes in early 20th-century United States. Industrialization was attracting people to cities from rural areas and gave rise to a new mass culture. Contributing factors leading to the Harlem Renaissance were the Great Migration of African Americans to northern cities, which concentrated ambitious people in places where they could encourage each other, and the First World War, which had created new industrial work opportunities for tens of thousands of people. Factors leading to the decline of this era include the Great Depression.

Religion

Christianity played a major role in the Harlem Renaissance. Many of the writers and social critics discussed the role of Christianity in African–American lives. For example, a famous poem by Langston Hughes, "Madam and the Minister", reflects the temperature and mood towards religion in the Harlem Renaissance.[13] The cover story for the Crisis Magazine′s publication in May 1936 explains how important Christianity was regarding the proposed union of the three largest Methodist churches of 1936. This article shows the controversial question about the formation of a Union for these churches.[14] The article "The Catholic Church and the Negro Priest", also published in the Crisis Magazine, January 1920, demonstrates the obstacles African–American priests faced in the Catholic Church. The article confronts what it saw as policies based on race that excluded African–Americans from higher positions in the church.[15]Discourse

Various forms of religious worship existed during this time of African–American intellectual reawakening. Although there were racist attitudes within the current Abrahamic religious arenas many African–Americans continued to push towards the practice of a more inclusive doctrine. For example, George Joseph MacWilliam presents various experiences, during his pursuit towards priesthood, of rejection on the basis of his color and race yet he shares his frustration in attempts to incite action on part of The Crisis Magazine community.[16]There were other forms of spiritualism practiced among African–Americans during the Harlem Renaissance. Some of these religions and philosophies were inherited from African ancestry.

For example, the religion of Islam traded in slaves from Africa as early as the 8th century through the Trans-Saharan trade. Islam came to Harlem likely through the migration of members of the Moorish Science Temple of America, which was established in 1913 in New Jersey.

Various forms of Judaism were practiced, such as Orthodox Judaism and Masorti Judaism and even Reformed Judaism, but it was Black Hebrew Israelites that founded their religious belief system during the late 20th century in the Harlem Renaissance.

Traditional forms of religion acquired from various parts of Africa were inherited and practiced during this era. Some commons examples were Voodoo and Santeria.

Criticism

Religious critique during this era was found in literature, art, and poetry. The Harlem Renaissance encouraged analytic dialogue that included the open critique and the adjustment of current religious ideas.One of the major contributors to the discussion of African–American renaissance culture was Aaron Douglas who, with his artwork, also reflected the revisions African Americans were making to the Christian dogma. Douglas uses biblical imagery as inspiration to various pieces of art work but with the rebellious twist of an African influence.[17]

Countee Cullen’s poem “Heritage” expresses the inner struggle of an African American between his past African heritage and the new Christian culture.[18] A more severe criticism of the Christian religion can be found Langston Hughes’ poem “Merry Christmas", where he exposes the irony of religion as a symbol for good and yet a force for oppression and injustice.[19]

Music

A new way of playing the piano called the Harlem Stride style was created during the Harlem Renaissance, and helped blur the lines between the poor Negroes and socially elite Negroes. The traditional jazz band was composed primarily of brass instruments and was considered a symbol of the south, but the piano was considered an instrument of the wealthy. With this instrumental modification to the existing genre, the wealthy blacks now had more access to jazz music. Its popularity soon spread throughout the country and was consequently at an all-time high. Innovation and liveliness were important characteristics of performers in the beginnings of jazz. Jazz musicians at the time such as Fats Waller, Duke Ellington, Jelly Roll Morton, and Willie "The Lion" Smith were very talented and competitive, and were considered to have laid the foundation for future musicians of their genre.[20][21] Duke Ellington gained popularity during the Harlem Renaissance. According to Charles Garrett, "The resulting portrait of Ellington reveals him to be not only the gifted composer, bandleader, and musician we have come to know, but also an earthly person with basic desires, weaknesses, and eccentricities." [22] Ellington didn't let his popularity get to him. He remained calm and focused on his music.During this period, the musical style of blacks was becoming more and more attractive to whites. White novelists, dramatists and composers started to exploit the musical tendencies and themes of African–Americans in their works. Composers used poems written by African-American poets in their songs, and would implement the rhythms, harmonies and melodies of African-American music—such as blues, spirituals, and jazz—into their concert pieces. Negroes began to merge with Whites into the classical world of musical composition. The first Negro male to gain wide recognition as a concert artist in both his region and internationally was Roland Hayes. He trained with Arthur Calhoun in Chattanooga, and at Fisk University in Nashville. Later, he studied with Arthur Hubbard in Boston and with George Henschel and Amanda Ira Aldridge in London, England. He began singing in public as a student, and toured with the Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1911.[23]

Fashion

During the Harlem Renaissance, Black America’s clothing scene took a dramatic turn from the prim and proper. Many young women preferred extreme versions of current white fashions - from short skirts and silk stockings to drop-waisted dresses and cloche hats.[24] The extraordinarily successful black dancer Josephine Baker, though performing in Paris during the height of the Renaissance, was a major fashion trendsetter for black and white women alike. Her gowns from the couturier Jean Patou were much copied, especially her stage costumes, which Vogue magazine called "startling." [25] Popular by the 1930s was a trendy, egret-trimmed beret. Men wore loose suits that led to the later style known as the "Zoot," which consisted of wide-legged, high-waisted, peg-top trousers, and a long coat with padded shoulders and wide lapels. Men also wore wide-brimmed hats, colored socks,[26] white gloves, and velvet-collared Chesterfield coats. During this period, African Americans expressed respect for their heritage through a fad for leopard-skin coats, indicating the power of the African animal.Characteristics and themes

Characterizing the Harlem Renaissance was an overt racial pride that came to be represented in the idea of the New Negro, who through intellect and production of literature, art, and music could challenge the pervading racism and stereotypes to promote progressive or socialist politics, and racial and social integration. The creation of art and literature would serve to "uplift" the race.There would be no uniting form singularly characterizing the art that emerged from the Harlem Renaissance. Rather, it encompassed a wide variety of cultural elements and styles, including a Pan-African perspective, "high-culture" and "low-culture" or "low-life," from the traditional form of music to the blues and jazz, traditional and new experimental forms in literature such as modernism and the new form of jazz poetry. This duality meant that numerous African-American artists came into conflict with conservatives in the black intelligentsia, who took issue with certain depictions of black life.

Some common themes represented during the Harlem Renaissance were the influence of the experience of slavery and emerging African-American folk traditions on black identity, the effects of institutional racism, the dilemmas inherent in performing and writing for elite white audiences, and the question of how to convey the experience of modern black life in the urban North.

The Harlem Renaissance was one of primarily African-American involvement. It rested on a support system of black patrons, black-owned businesses and publications. However, it also depended on the patronage of white Americans, such as Carl Van Vechten and Charlotte Osgood Mason, who provided various forms of assistance, opening doors which otherwise would have remained closed to the publication of work outside the black American community. This support often took the form of patronage or publication. Carl Van Vechten was one of the most notorious white Americans involved with the Harlem Renaissance. He allowed for assistance to the black American community because he wanted racial sameness.

There were other whites interested in so-called "primitive" cultures, as many whites viewed black American culture at that time, and wanted to see such "primitivism" in the work coming out of the Harlem Renaissance. As with most fads, some people may have been exploited in the rush for publicity.

Interest in African-American lives also generated experimental but lasting collaborative work, such as the all-black productions of George Gershwin's opera Porgy and Bess, and Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein's Four Saints in Three Acts. In both productions the choral conductor Eva Jessye was part of the creative team. Her choir was featured in Four Saints.[27] The music world also found white band leaders defying racist attitudes to include the best and the brightest African-American stars of music and song in their productions.

The African Americans used art to prove their humanity and demand for equality. The Harlem Renaissance led to more opportunities for blacks to be published by mainstream houses. Many authors began to publish novels, magazines and newspapers during this time. The new fiction attracted a great amount of attention from the nation at large. Among authors who became nationally known were Jean Toomer, Jessie Fauset, Claude McKay, Zora Neale Hurston, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, Omar Al Amiri, Eric D. Walrond and Langston Hughes.

The Harlem Renaissance helped lay the foundation for the post-World War II phase of the Civil Rights Movement. Moreover, many black artists who rose to creative maturity afterward were inspired by this literary movement.

The Renaissance was more than a literary or artistic movement, as it possessed a certain sociological development—particularly through a new racial consciousness—through ethnic pride, as seen in the Back to Africa movement led by Marcus Garvey. At the same time, a different expression of ethnic pride, promoted by W. E. B. Du Bois, introduced the notion of the "talented tenth": those Negroes who were fortunate enough to inherit money or property or obtain a college degree during the transition from Reconstruction to the Jim Crow period of the early twentieth century. These "talented tenth" were considered the finest examples of the worth of black Americans as a response to the rampant racism of the period. (No particular leadership was assigned to the talented tenth, but they were to be emulated.) In both literature and popular discussion, complex ideas such as Du Bois's concept of "twoness" (dualism) were introduced (seeThe Souls of Black Folk (1903).[28] Du Bois explored a divided awareness of one's identity that was a unique critique of the social ramifications of racial consciousness. This exploration was later revived during the Black Pride movement of the early 1970s.

Influence

A new Black identity

The Harlem Renaissance was successful in that it brought the Black experience clearly within the corpus of American cultural history. Not only through an explosion of culture, but on a sociological level, the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance redefined how America, and the world, viewed African–Americans. The migration of southern Blacks to the north changed the image of the African–American from rural, undereducated peasants to one of urban, cosmopolitan sophistication. This new identity led to a greater social consciousness, and African–Americans became players on the world stage, expanding intellectual and social contacts internationally.

The progress—both symbolic and real—during this period became a point of reference from which the African-American community gained a spirit of self-determination that provided a growing sense of both Black urbanity and Black militancy, as well as a foundation for the community to build upon for the Civil Rights struggles in the 1950s and 1960s.

The urban setting of rapidly developing Harlem provided a venue for African Americans of all backgrounds to appreciate the variety of Black life and culture. Through this expression, the Harlem Renaissance encouraged the new appreciation of folk roots and culture. For instance, folk materials and spirituals provided a rich source for the artistic and intellectual imagination, which freed Blacks from the establishment of past condition. Through sharing in these cultural experiences, a consciousness sprung forth in the form of a united racial identity.

Criticism of the movement

Many critics point out that the Harlem Renaissance could not escape its history and culture in its attempt to create a new one, or sufficiently separate from the foundational elements of White, European culture. Often Harlem intellectuals, while proclaiming a new racial consciousness, resorted to mimicry of their white counterparts by adopting their clothing, sophisticated manners and etiquette. This "mimicry" may also be called assimilation, as that is typically what minority members of any social construct must do in order to fit social norms created by that construct's majority. This could be seen as a reason that the artistic and cultural products of the Harlem Renaissance did not overcome the presence of White-American values, and did not reject these values. In this regard, the creation of the "New Negro" as the Harlem intellectuals sought, was considered a success.The Harlem Renaissance appealed to a mixed audience. The literature appealed to the African-American middle class and to whites. Magazines such as The Crisis, a monthly journal of the NAACP, and Opportunity, an official publication of the National Urban League, employed Harlem Renaissance writers on their editorial staffs; published poetry and short stories by black writers; and promoted African-American literature through articles, reviews, and annual literary prizes. As important as these literary outlets were, however, the Renaissance relied heavily on white publishing houses and white-owned magazines. A major accomplishment of the Renaissance was to open the door to mainstream white periodicals and publishing houses, although the relationship between the Renaissance writers and white publishers and audiences created some controversy. W. E. B. Du Bois did not oppose the relationship between black writers and white publishers, but he was critical of works such as Claude McKay's bestselling novel Home to Harlem (1928) for appealing to the "prurient demand[s]" of white readers and publishers for portrayals of black "licentiousness".[30] Langston Hughes spoke for most of the writers and artists when he wrote in his essay "The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain" (1926) that black artists intended to express themselves freely, no matter what the black public or white public thought.[31] In Langston Hughes' writings, he also returned to the theme of racial passing, but during the Harlem Renaissance, he began to explore the topic of homosexuality and homophobia. He began to use disruptive language in his writings. He explored this topic because it was a theme that during this time period was not discussed.[32]

African-American musicians and other performers also played to mixed audiences. Harlem's cabarets and clubs attracted both Harlem residents and white New Yorkers seeking out Harlem nightlife. Harlem's famous Cotton Club, where Duke Ellington performed, carried this to an extreme, by providing black entertainment for exclusively white audiences. Ultimately, the more successful black musicians and entertainers who appealed to a mainstream audience moved their performances downtown.

Certain aspects of the Harlem Renaissance were accepted without debate, and without scrutiny. One of these was the future of the "New Negro". Artists and intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance echoed American progressivism in its faith in democratic reform, in its belief in art and literature as agents of change, and in its almost uncritical belief in itself and its future. This progressivist worldview rendered Black intellectuals—just like their White counterparts—unprepared for the rude shock of the Great Depression, and the Harlem Renaissance ended abruptly because of naive assumptions about the centrality of culture, unrelated to economic and social realities.

21-3a 1920s Popular Culture

Music

Through all his riverboat experience Armstrong's musicianship began to mature and expand. At twenty, he could read music and started to be featured in extended trumpet solos, one of the first jazzmen to do this, injecting his own personality and style into his solo turns. He had learned how to create a unique sound and also started using singing and patter in his performances. In 1922, Armstrong joined the exodus to Chicago, where he had been invited by his mentor, Joe "King" Oliver, to join his Creole Jazz Band and where he could make a sufficient income so that he no longer needed to supplement his music with day labor jobs. It was a boom time in Chicago and though race relations were poor, the city was teeming with jobs available also for black people, who were making good wages in factories and had plenty to spend on entertainment.

Oliver's band was among the most influential jazz bands in Chicago in the early 1920s, at a time when Chicago was the center of the jazz universe. Armstrong lived luxuriously in Chicago, in his own apartment with his own private bath (his first). Excited as he was to be in Chicago, he began his career-long pastime of writing nostalgic letters to friends in New Orleans. As Armstrong's reputation grew, he was challenged to "cutting contests" by hornmen trying to displace the new phenomenon, who could blow two hundred high Cs in a row. Armstrong made his first recordings on the Gennett and Okeh labels (jazz records were starting to boom across the country), including taking some solos and breaks, while playing second cornet in Oliver's band in 1923. At this time, he met Hoagy Carmichael (with whom he would collaborate later) who was introduced by friend Bix Beiderbecke, who now had his own Chicago band.

Armstrong enjoyed working with Oliver, but Louis' second wife, pianist Lil Hardin Armstrong, urged him to seek more prominent billing and develop his newer style away from the influence of Oliver. Armstrong took the advice of his wife and left Oliver's band. For a year Armstrong played in Fletcher Henderson's band in New York on many recordings. After playing in New York, Armstrong returned to Chicago, playing in large orchestras; there he created his most important early recordings. Lil had her husband play classical music in church concerts to broaden his skill and improve his solo play and she prodded him into wearing more stylish attire to make him look sharp and to better offset his growing girth. Lil's influence eventually undermined Armstrong's relationship with his mentor, especially concerning his salary and additional moneys that Oliver held back from Armstrong and other band members. Armstrong and Oliver parted amicably in 1924. Shortly afterward, Armstrong received an invitation to go to New York City to play with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra, the top African-American band of the time. Armstrong switched to the trumpet to blend in better with the other musicians in his section. His influence upon Henderson's tenor sax soloist, Coleman Hawkins, can be judged by listening to the records made by the band during this period.

Armstrong quickly adapted to the more tightly controlled style of Henderson, playing trumpet and even experimenting with the trombone. The other members quickly took up Armstrong's emotional, expressive pulse. Soon his act included singing and telling tales of New Orleans characters, especially preachers. The Henderson Orchestra was playing in prominent venues for white-only patrons, including the famed Roseland Ballroom, featuring the arrangements of Don Redman. Duke Ellington's orchestra would go to Roseland to catch Armstrong's performances and young hornmen around town tried in vain to outplay him, splitting their lips in their attempts.

During this time, Armstrong made many recordings on the side, arranged by an old friend from New Orleans, pianist Clarence Williams; these included small jazz band sides with the Williams Blue Five (some of the most memorable pairing Armstrong with one of Armstrong's few rivals in fiery technique and ideas, Sidney Bechet) and a series of accompaniments with blues singers, including Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, and Alberta Hunter.

Armstrong returned to Chicago in 1925 due mostly to the urging of his wife, who wanted to pump up Armstrong's career and income. He was content in New York but later would concede that she was right and that the Henderson Orchestra was limiting his artistic growth. In publicity, much to his chagrin, she billed him as "the World's Greatest Trumpet Player". At first, he was actually a member of the Lil Hardin Armstrong Band and working for his wife. He began recording under his own name for Okeh with his famous Hot Five and Hot Seven groups, producing hits such as "Potato Head Blues", "Muggles", (a reference to marijuana, for which Armstrong had a lifelong fondness), and "West End Blues", the music of which set the standard and the agenda for jazz for many years to come.

The group included Kid Ory (trombone), Johnny Dodds (clarinet), Johnny St. Cyr (banjo), wife Lil on piano, and usually no drummer. Armstrong's band leading style was easygoing, as St. Cyr noted, "One felt so relaxed working with him, and he was very broad-minded ... always did his best to feature each individual." Among the most notable of the Hot Five and Seven records were "Cornet Chop Suey," "Struttin' With Some Barbecue," "Hotter Than that" and "Potato Head Blues,", all featuring highly creative solos by Armstrong. His recordings soon after with pianist Earl "Fatha" Hines (most famously their 1928 "Weatherbird" duet) and Armstrong's trumpet introduction to and solo in "West End Blues" remain some of the most famous and influential improvisations in jazz history. Armstrong was now free to develop his personal style as he wished, which included a heavy dose of effervescent jive, such as "whip that thing, Miss Lil" and "Mr. Johnny Dodds, Aw, do that clarinet, boy!"

Louis Armstrong - West End Blues, 3:21

https://youtu.be/4WPCBieSESI